By Karen Rubin, with Eric Leiberman and Sarah Falter

Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

On our third morning on the Inca Trail, we are wakened at 5 am at our tents in the Chaquiccocha campsite to be packed up, have breakfast at 5:30 am and out by 6:30 am to begin what is generally considered the most relaxed day of the four-day trek, when our Alpaca Expeditions group will hike 6.2 miles mostly downhill, and visit two Inca sites, Phuyupatamarka (‘Town in the Clouds”) and Intipata (“Terraces of the Sun”), before reaching the campsite, where, we are told, a special activity awaits.

I’m still on a high from surviving Day 2 and the dual challenges of Dead Woman’s Pass and Runcuraccay Pass, so I feel I can handle anything (and not just on this trek).

It’s a foggy morning and before setting out, our guide Lizandro organizes all of us in a great circle with the porters and staff and guests (Giorgio calls us “family” and Lizandro calls us “team” and both are true in the way we have bonded) so we meet each other. We learn that the porters all come from one mountain village, that two are brothers, 62 and 68 years old, that one of the porters is a woman (very unusual, but Alpaca Expeditions has made an effort to recruit women).

We trekkers introduce ourselves, also, and I mention that today is my 71st birthday – mentioning it because I am pretty pleased with the achievement (and our guide, Giorgio, at one point guessed I was 55 – perhaps just being polite) – to emphasize that they have made this experience of a lifetime possible for me.

We hike for 2 hours along what they call “Inca flat” (gradual inclines) and begin to enter the jungle, known as the Cloud Forest. As we walk, we have the opportunity to see Salkantay, the second highest snow-capped mountain in the Sacred Valley, and get glimpses of a fantastic panoramic view of the Vilcabamba mountain range through mist and clouds.

We make our way up to the last peak and our third pass, Phuyupatamarka (“Temple Above the Clouds”) at 12,073 ft. from where we have great views overlooking the Urubamba River. Down the valley, we get our first view of Machu Picchu Mountain, but the famous “Lost City” itself is still hidden from view.

From Phuyupatamarka it´s a 3-hour walk down a flight of stone steps to our last campsite and the grand finale for this day, exploring the Incan site of Wiñaywayna (“Forever Young”).

On the descent, we stop in a small cave, and just as the pilgrims did 600 years ago as they came closer to Machu Picchu, the religious center, Lizandro uses this site, the Temple Above the Clouds, to discuss religious beliefs and practices at the time of the Inca.

This would have been one of the religious sites where pilgrims 600 years ago would be able to show their devotion and purify themselves before they reached the sacred Machu Picchu. It would have been a place of offerings, a ritual shower, of sacrifice.

At the time of the Inca and thousands of years before, the many different tribes were polytheists, worshipping many gods mostly associated with Nature. They believed that nature, man and the Pachamama (Mother Earth), lived in harmony and perpetual interrelationship. The Inca state promoted the worship of a Creator God (Wiracocha), Sun God (Inti), Moon Goddess (Mamaquilla), Thunder God (Illapa) and Earth Mother (Pachamama), and a host of other supernatural entities. But the ruling Inca established Inti, the sun god, as the most important (the first Inca king declared himself to be the son of Inti, to establish his divine power and authority).

Lizandro points to a trinity that organizes the belief system: “The Inca thought three lives (past, present and future) ran parallel – one underneath (past), one above (future). They divided the world in three dimensions, three stages of life, which they depicted with animals – the condor (the heavens), the puma (the middle world of earth), and the snake (the underworld).

The snake represents knowledge, wisdom; because everything known is from past; the puma represents strength, energy; the condor connects this world to next world because it could touch heaven and carry heavy things, he says.

“The Inca saw life as a circle, not a line, so life never ends. They believed life is reborn and when they were buried, they were placed in the fetal position pointing to the sun and mountains; rulers were mummified and their mummified remains taken and paraded around one day a year. Children didn’t inherit property – people were buried with their belongings (for the next life). Machu Picchu, a sacred place, would have taken more than a lifetime to build, but though Emperor Pachacuti believed he wouldn’t enjoy it in this world, he would in the next.”

And the linchpin to it all, the basis for the Inca emperor’s power and authority, was religious faith.

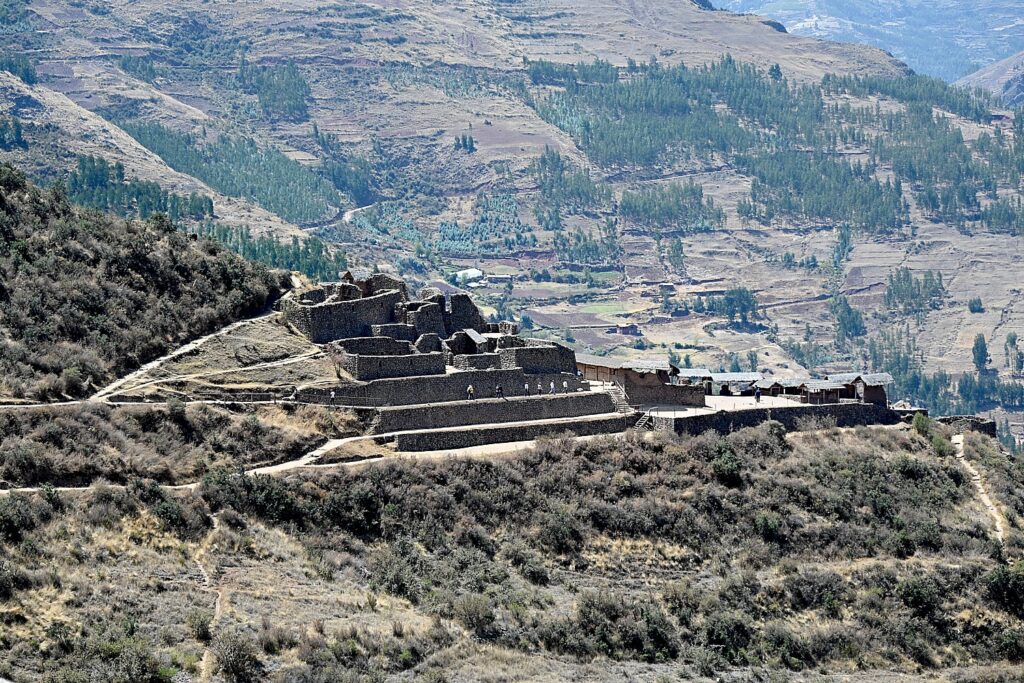

So, while the Inca did not have slaves, they had a system of labor, whereby the men would give two to three months of service to the rulers (the first Inca Emperor, Pachacútec, the Alexander the Great of the Inca, had them build Machu Picchu, Pisac, Ollantaytambo and the various palaces and temples), and gave 50 percent of what they harvested to the nobles and the priests out of religious devotion. And the people were kept ignorant – only the nobles and priests were educated – so they could be controlled with the use superstition and miracles.

He says there would have been six water fountains here – so people could take a ritual shower “to purify mind and body before going to Machu Picchu.” He also points to a sacrificial rock.

There appears to be an altar carved into the bedrock facing sunrise.

We have about 45 minutes of a steep downward hike before it levels off again.

We come to an Inca site, Intipata (Terraces of the Sun) that interestingly, overlooks our final campsite waaaay down the mountain. Lizandro points out what would have been a platform for sacrifice. “Not for human. That would be rare” indicating that it would take place only in extreme circumstances, like a famine and would be mainly girls 11 and 13 years old who belonged to Cuzco noble families, who were told they were born to be sacrificed as offerings to stop a national disaster. He describes one instance when the king sacrificed his daughter. (I’ll bet it was a period of famine, because they needed to reduce population to keep in balance.) The sacrificed were given fresh vegetable hallucinogenic flower to eat. “They offered them not death, but life.”

More typically, it was a llama that would be sacrificed. “The llama represents spiritual life and the black llama, a symbol of material life, would be sacrificed.”

The Inca did not have a written alphabet, yet they had to figure ways to communicate across distances – to alert the villages along the Inca Trail when the king was coming, when enemies approached. They did it using runners – sometimes in relays (they could do the 26 mile distance we do in four days in four hours), using conch trumpets. Also, the patterns and colors of their clothing would identify who they were, what tribe, and so, whether friend or foe.

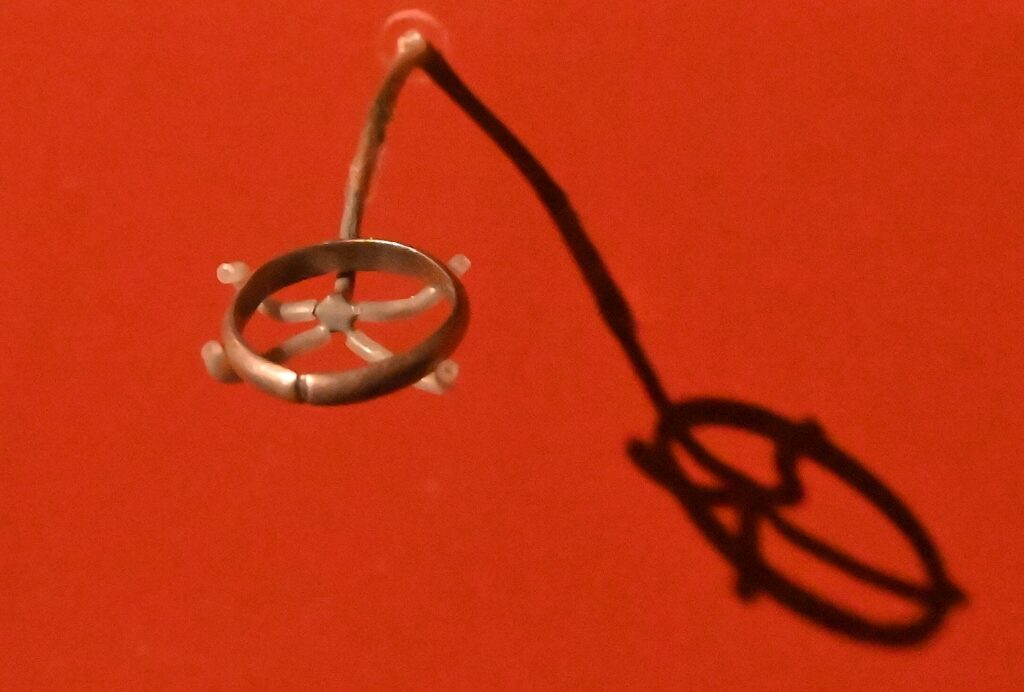

But they also had a system of colored strings and knots, called quipu, that recorded and relayed information, which he shows us as an example. Lizandro says (not disguising his resentment) that only a few quipu have survived but many have been taken to foreign museums (in fact, most of what the archeologists have taken from the Inca sites have yet to be returned).

(I imagine that the quipu could be read like Morse code and while they did not have an alphabet, the code was probably based on mathematics, so perhaps a computer could decipher?)

At the end of this relatively short and easy third day’s hike, we get into camp at 1 pm (it doesn’t feel like five hours!) and Lizandro tells us to look forward to a special “activity”. This turns out to be a cooking class, where Chef Mario shows us how to cook a popular Peruvian dish, lomas latudo. We get chef’s hats and aprons and the platters of ingredients – beef, red pepper, tomatoes, onions, yellow pepper, ginger, garlic, vinegar, soy sauce, salt, pepper, cilantro, oil to fry potato (served with French fries and rice) – which we learn how to properly cut, dice, stir and sauté – before enjoying our handiwork for lunch.

Later in the afternoon, after time to relax, we walk a surprisingly short distance (less than 10 minutes) along a trail from our campsite to one of the most impressive Incan villages of all, Wiñaywayna, and (unlike when we go to Machu Picchu the next day) we have it almost to ourselves to explore.

Wiñaywayna is the most spectacular Inca site on the trail after Machu Picchu and the most popular campsite because of its proximity to Machu Picchu.

Wiñaywayna was discovered by a local archeologist in 1942 who was excavating a different site, Chamchabamba, and found it hidden under dense vegetation and cloud forest. Amazingly, they found orchid flowers growing on the wall. Lizandro explains that Peru has 435 species orchids, but they mostly bloom early or at the end rainy season, some bloom only every 4-5 years or for only one day year, opening at sunrise and dying at sunset. But the orchids found here bloom year round, which is why they named the site, Wiñaywayna – Forever Young – for the orchid. (If Dead Woman’s Pass, thankfully, did not prove prescient for me, perhaps Forever Young on this, my birthday?)

We explore the site, climbing up and down the steep stone steps, walking through the corridors, really getting into the architecture and engineering, the logistics, as if the people left only yesterday. You realize these ruins were buried under overgrowth for 400 years and can only marvel at what was involved in its excavation so that we can appreciate it today.

Most of the Inca sites have yet to be uncovered and are still buried, and the ones that we do see have only been partially excavated. Indeed, only about 40 percent of Machu Picchu has been excavated.

We go through a room with three walls and big windows which, Lizandro tells us, means it was a storage room – the windows provided ventilation for better preservation, while homes had no windows because it would be too cold; instead, there are spaces in the walls where they would put idols for decoration.

We see what would have been a watch tower. There would have been guards with weapons at the ready to protect Machu Picchu – like sling shots (a rope of wool with a bag in the middle with rocks), arrows, lances, spears, hatchets – fine for use against another tribe, but fairly useless against the weapons the Spanish invaders wielded. The guard would have been able to recognize if someone coming was friend or foe by the colors and design of their clothes.

The temple here has three different architectural styles, which Lizandro says shows it was built by different generations and different engineers. A wall of this temple has seven windows that look out to the peak, arranged in a curve. The round shape was to reflect the sun, to provide different places to observe sun, like a sun dial. The seven windows are homage to the Seven Sister stars of the Pleiades.

The terraces here at Wiñaywayna were Incan agricultural laboratories – narrow and concave to follow the curves of the mountain, every seven levels a different ecology, granite and quartz used to absorb heat from the sun to keep plants from freezing overnight. “The Inca realized that elevations produced better potato and corn adapted to altitude.”

This site, along with the others, were purposely abandoned in 1538 with the Spanish conquest.

The first Spanish expedition, in 1532, had only 167. “They were invaders, not explorers. They came to destroy the culture, the civilization. They took gold and silver and brought disease,” Lizandro says. The population at the time of the Inca was as high as 18 million before the Spanish.

Machu Picchu and the other sites were built in the mid 1400s, over a period of about 60 years. Less than 100 years later, the population started decreasing– the human ecologist in me can’t help but wonder if the massive building projects and empire building didn’t take its toll on the population.

“European diseases came even before the Spaniards came. Cortez brought disease to the Mayans, and the Mayans, trying to flee the Spaniards by going south, carried the diseases along the same network of roads the Inca used to conquer and unify its empire. The 12th Incan king, Huayna Cápac (it is believed) died in 1525 from smallpox and there was no king to follow.”

He says that it is wrong to think of an Incan civilization, rather than an Incan ruler and ruling family of perhaps 20,000 who dominated a population that ranged in size from 10 to 20 million. “When he passed away, he was mummified to continue guiding.” Because the Inca ruler could have as many concubines as he wanted, Huayna Cápac likely had 500 children throughout the kingdom, but only three who were sons of the Queen, were in line to be king. Two of the brothers were fighting a civil war for control at the time the Spanish came to Cuzco in 1533,” another reason the Spanish were successful with their conquest.

“The Spaniards saw amazing gold, silver – a city of gold – buildings covered in gold, a temple that had life-sized animals of gold. The Spaniards melted them to make coins. Then the Spanish king sent more soldiers.”

The Incan kingdom, weakened by civil war and not exactly supported by the masses they had subjugated for a century, abandoned this place to protect Machu Picchu, which was holy to them, like the Vatican. Machu Picchu was hidden amid the mountain peaks. To protect it from the Spanish invaders, the Inca destroyed the trails that led to Machu Picchu, and ultimately, abandoned Machu Picchu as well, making a last stand at Vilcabamba.

“The Inca weren’t the nicest to build such a civilization. For 100 years, they had to kill to control, so not all people were happy, so they didn’t help the Inca against the Spanish,” Lizandro says.

None of these grand projects were ever finished, which is more understandable than if they were completed.

We have as much time as we want to explore until darkness begins to fall because we can just stroll back to the campsite.

When we sit down to dinner, Chef Mario presents me with the most amazing birthday cake I have ever had in my life – completely decorated. It took him three hours to prepare it with the camping equipment he cooks with. I share the cake with Peter who timed his bucketlist Machu Picchu ascent for his 35th birthday the next morning.

Lizandro then asks us what time we would like to wake up in order to get to the check point to Machu Picchu before the other 200 trekkers who will be on line: “3 am? No? Then 3:01,” he says, noting that he has a 98% success rate in being first in line for the checkpoint when it opens at 5:30 am. The check point is only about 10 minutes walk from the campsite. Why so important to be first? Well, to get to the Sun Gate by sunrise, and before the small space gets jammed crammed with people all elbowing to get the best views and photos.

Tomorrow is the day we will reach the goal of our trek: Machu Picchu.

The permits to do the Inca Trail trek to Machu Picchu are limited to 500 a day for all the trekking companies (which includes 200 for trekkers and 300 for porters and staff) and get booked up months in advance.

More information: Alpaca Expeditions, USA Phone: (202)-550-8534, [email protected], [email protected], https://www.alpacaexpeditions.com/

Next: Day 4 on the Inca Trail – Machu Picchu!

See also:

VISIT TO PERU’S SACRED VALLEY IS BEST WAY TO PREPARE FOR INCA TRAIL TREK TO MACHU PICCHU

INCAN SITES OF PISAC, OLLANTAYTAMBO IN PERU’S SACRED VALLEY ARE PREVIEW TO MACHU PICCHU

ALPACA EXPEDITIONS’ INCA TRAIL TREK TO MACHU PICCHU IS PERSONAL TEST OF MIND OVER MATTER

DAY 1 ON THE INCA TRAIL TO MACHU PICCHU: A TEST

DAY 2 ON THE INCA TRAIL TO MACHU PICCHU: DUAL CHALLENGES OF DEAD WOMAN´S PASS, RUNCURACCAY

DAY 3 ON THE INCA TRAIL TO MACHU PICCHU: TOWN IN THE CLOUDS, TERRACES OF THE SUN & FOREVER YOUNG

DAY 4 ON THE INCA TRAIL: SUN GATE TO MACHU PICCHU, THE LOST CITY OF THE INCAS

__________________

© 2022 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to [email protected]. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures