By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

(On September 3, 2016, President Obama traveled to Hangzhou, China for a ceremony in which the United States and China formally joined the Paris Agreement. This is sure to spark interest in visiting this enchanting destination that I so enjoyed experiencing a few years ago. This story was originally published in 2008.)

Through its 5,000 years of human habitation, Hangzhou, a city on China’s southeastern coast about two hours drive south of Shanghai, has been called many things – Xifu, Li’An; Marco Polo referred to the city as Kinsay.

I have spent three days touring Hangzhou and the Zhejiang Province with a guide and a driver provided by the Zhejiang Provincial tourist office. They have given me a fairly good orientation to the city (see related story, Hangzhou: China’s City of Romance). I am very grateful for having had them, because it would have been difficult to figure out in the short time I had what to see and how to see important sites travel without the ability to speak and read the language. (Americans coming to China can arrange for escorted tours through several different agencies, though I did not find an easy way to hire a car and English-speaking driver.)

But for my fourth and final day in Hangzhou, I am completely on my own and I am eager to explore the city on foot (and by bicycle, as it turns out). Frankly, what made me anxious was the prospect of crossing the street.

Hangzhou is a city that seems eternal for preserving its ancient heritage, but it is manifestly modern in its economic and social development. Instead of quaint narrow streets and bicycles, it has massive boulevards just crammed with cars, people riding mopeds and bicycles, all manner of vehicles and people crisscrossing, and it seems that in this mashing of man and machine, the cars have right of way – pedestrians better get out of it.

I am in the minority, it seems, in trying to merely walk on the sidewalk. But the first time I cross the street from my hotel (they have pedestrian crossing signs and some of the intersections have traffic controllers) I am okay.

I have planned my day to just wander around the city – I have a general idea and one specific destination in mind – rather than figure out public buses or hire a taxi to get to more distant places. I have plotted my course. Most of the main streets, thankfully, have English transliteration of the names on signs (something they didn’t have when I was last in China). The problem is that the spelling is not always consistent. But this is my adventure and I imagine myself Marco Polo coming into a completely foreign place.

I have prepared in advance by taking away the Capital Star Hotel card in Chinese and English, with the directions; also, my guide has written a list of places she recommended I visit, in Chinese and English. And I know that if I run into trouble, I can just to go any hotel and hail a cab. And of course, I have my street maps and handy tourist guide.

Walking about on your own is an entirely different experience than being driven places. Driving, the world unfolds like a grand tableaux – I notice, for example, buses wrapped with boldly colored advertising (even a bit risqué) on the side and such sights as the Family Planning Publicity & Technical Guidance Station of Hangzhou City.

But walking, you can choose the pace and take time to really observe things – shopkeepers opening their shops, commuters making their way to work having conversations with each other as they ride side by side on mopeds, grandparents biking their grandkids to school. Because you don’t understand the language, it is as if you are watching television without the sound – you find yourself intently focusing on details. You watch daily life unfold in real time. You also get to interact with people.

More importantly, you can follow an inner spirit, a whim.

The city itself is crowded with cars and skyscrapers, but now that I have the time to look at them more closely, many show pleasing architecture, not the sterile, institutional, massive apartment buildings that you might have imagined would have been built hurriedly, in order to accommodate the needs of the 1.5 million who live downtown and a burgeoning economy. The buildings have big windows and actually are built with light and air around. And everywhere I look, there are plantings – Hangzhou prides itself on being a “green” city. Here, at least, the oppressive pollution that I have heard about in other major cities, has not taken hold – no doubt because of the large amount of greenspace, national and protected lands, and the vast West Lake, itself.

At a major intersection, where the roads seem to diverge a bit, I stop to study the map (okay, I am a little confused), and a young woman wearing a leather cowboy hat asks in wonderful English if I need any help – she has just come from making a film in Tibet (I don’t ask her about the riots that had just taken place).

I have walked from my hotel in virtually a straight line, down South Hushu Road, which turns into Wulin Road, called “the Fashionable women’s garment street” on the map. This reminds me that Hangzhou is considered the capital of women’s fashion. Wulin is a street of boutiques with very fashionable clothes, western music playing, and ads on the street with western faces.

A little further on young man on a moped stops, intrigued by seeing a Westerner. “Where are you from?” he asks. “USA? America is wonderful.”

I have been surprised, in fact, that my presence (I am the only Westerner around that I can see), barely catches anyone’s notice. I had been in the first wave of Westerners to penetrate the Bamboo Curtain that had kept China virtually in isolation for decades, during my last two visits, in 1978 and 1980; today, you have the feeling that the Chinese are not so insulated, despite the government control of the media. This is probably because of all the multinationals setting up factories and other commercial ventures, and because television, even though limited, does offer some American movies. Whether or not they are actually still behind some curtain of censorship, the people don’t necessarily reflect it.

I continue on my way and come to the Anji Road Experimental School, built in 1954, where children are playing in a courtyard. The name and date intrigues me, and I wonder how teaching has changed from those days.

I finally come to West Lake and see a bicycle rental stand. I figure it will be great for transportation, if not for a chance to see more of the lake. The cost is 10 yuan (about $1.50) an hour, with a 300Yuan deposit, about $45, including the use of a bike lock and helmet. (My guide had made mention of the 300 Yuan deposit, so I am prepared, and we are able to have this conversation with the rental guy without actually understanding each other).

There are many bike rental stations around the lake; you can also get around by a golf cart – either hailing one like a cab, or chartering one.

Once I have the bike, though, I feel I have wings – I am not so brave as to tackle the major streets which are much too congested for me, but stick around the Lake and the side streets. Even here, though, it gets fairly frantic. I am thankful that it is a very low bike, and I can quickly put a foot down when I need to.

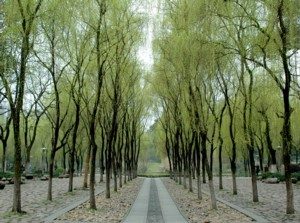

It is this wonderful sense of adventure, of having no schedule, no itinerary, just following a whim that makes the day particularly exciting. I follow whatever seems interesting, and so I find myself following the willows and the purple blossoms, and come to West Lake, again.

I stop at an archway made of these graceful willow trees, and come upon the statue of Qian, the first king of Wu, and then to the memorial to him, the Temple of King Qian (15 Y, about $2 entrance). Qian Liu, who lived from 852-932, was born in Lin’an (later called Hangzhou) and in 923 established the Wu Yue Kingdom with Hangzhou as the capital.

From what I read, Qian Liu sounds like a fascinating man. He was born to a peasant family and made his living selling salt. He joined the army when he was 20, and “suppressed war chaos of military governors.”

A curious artifact on exhibit is a replica of the Iron Certificate that Qian Liu received from the Emperor, in 895, for suppressing rebel official Dong Chang. The certificate basically exempts King Qian and his descendants from the death penalty and other legal penalties.

“The iron certificate was lost in wartime but found by fisherman in deep water,” the notes read. “Descendents of Qian bartered it back with rice. It had been for sale in bazaar.”

In 923, Qian Liu became King of the Wu Yue. He is revered for “guarding the border and keeping the people at rest, including initiating no war, converting people, awarding cultivation and weaving, building irrigation works, dredging West Lake, recruiting talent and developing trade.

“He built irrigation system and sericulture [raising silk worms for the production of raw silk], treated subordinates well and enlisted competent people.” Under his rule, the notes say, “Hangzhou became the #1 city in Southeast China in prosperity.”

He died at the age of 81 and was followed by four other Qian kings from three generations (one became king at the age of 14 and another lasted only six months).

Hangzhou served as the capital of the Wuyue Kingdom for 200 years; the city reached its zenith of power in the period just before China was invaded by the Mongols, in 1276. By then, the city had nearly a million people, making it one of the most populous cities in the world.

Though it was no longer a capital, Italian explorer Marco Polo found it a beautiful city even after the Mongol conquest. During the years of the great Kublai Khan, 100 years after the Mongol conquest, Polo wrote, “[It is] beyond dispute the finest and the noblest in the world. The number and wealth of the merchants, and the amount of goods that passed through their hands, was so enormous that no man could form a just estimate….”

All through my visit to various historic sites, I try to absorb as much as I can, but it is very difficult – for one thing, you are dealing with thousands of years of history, with dates based on dynasties and kingdoms; for another, the spellings and names of places and people are not consistent, and for an American, it is often difficult to distinguish the Chinese names because of the different transliterations. Even maps are hard to follow because they don’t always use the same English names or transliterations. But that is part of the fun of discovery – pieces of the puzzle come closer together.

As I leave the King Qian’s memorial hall, I hear “Auld Lang Syne” playing in the orchard of willows. I follow the willows and then I follow purple flowers, and come again to the water’s edge. I am pulled in two ways: Spend more time at the magnificent West Lake, perhaps to ride completely around it (about 15 miles or so), or to go in search of Hefang Street and the Museum of Traditional Chinese Medicine?

I make my way to Hefang Street, which turns out to be an ancient market street that seems little changed from the centuries, and in fact, epitomizes the history and culture of Hangzhou.

When the Southern Song Dynasty set up Hangzhou as its capital, a ten-li (li is a measure of distance, 500 meters or 547 yards) royal street was opened. Today, there are more than 100 shops including teahouses, drug stores, silk shops, baked goods, food, curios, calligraphy and paintings, and some noted shops including the Wanlong Ham Workshop and Wangsingji fans, that line the promenade, including a massive multi-story market building where you can buy fresh flowers, fresh fish, and just about anything else. But the most famous, is the Hu Qing Yu Tang Drugstore.

Chinese Medicine Museum

My key objective for the day is to find the Museum of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Hu Qing Yu Tang Chinese Medicine Museum), but I am having trouble figuring out where it is (largely because the maps don’t conform). I look down a narrow alley that seems intriguing and see giant Chinese characters on a wall and an arrow pointing down the street. I feel compelled to follow the arrow, and sure enough, almost by accident, I come upon the entrance to the museum.

I pay the 10Y fee ($1.40), and follow the signs: “Upstairs, Visitor” and “Onwards, Visitor.”

The first museum dedicated to Chinese medicine in China, it is located within a fantastic house like a palace and today, one of the finest examples of architecture that remains from the late Qing Dynasty. It is exactly as the brochure says, “ingenious in layout, antique in form, most well preserved”. The structure is a significant attraction in itself.

This is the site of the Hu Qingyutang Chinese Pharmacy founded in 1874 by Hu Xueyan, who is identified as “a red-hat businessman”. A man of modest background, I learn, he made his money by raising food and supplying the government during a period of rebellion. As a reward, he was crowned by the Emperor Tongzhi of Qing Dynasty with the top rank and bestowed a yellow mandarin jacket.

He became fantastically wealthy, owned an enormous amount of real estate, and founded the pharmacy as his way of giving back to the community. But in 1883, he began to invest in silk and “failed in competition with foreign adventurers, went bankrupt and two years later, died of depression.”

I am intrigued by the Hu Xueyan motto: “Refraining from cheating.” In fact, on display is a “Deception Warning Tablet”. According to the brochure, Hu Xueyan instructed salesclerks to raise deer and, dressed in livery uniform, parade them when the Idrodeer pill was being prepared. The deer was killed in public to show that the ingredients were “true” and there was no deception.

The art, relics, architecture of the museum are simply fantastic – as you roam from room to room, exhibit to exhibit. In fact, the brochure says this is the largest ancient commercial building hall in the country.

The exhibit lays out the fundamentals of traditional Chinese medicine, and asks and answers, “How did it come about? In a primitive society, hungry people are forced to eat anything – they ate poisonous plants and suffered vomiting, diarrhea, coma, even death; sometimes they ate and found the poison alleviated.”

Archeology on the lower reaches of the Yangtze showed the use of traditional medicine from 6000-7000 years ago. Marco Polo also described traditional medicine.

In the exhibition hall, the history of Chinese traditional medicine is demonstrated through a great number of items and descriptions, including anecdotes of famous Chinese doctors in history.

A legend of one of the founders of the science of Chinese medicine is quoted: “’Shennong tasted every herb and met poisoning 10 times a day’ – through numberless intentional and accidental trials, found what worked.”

Other early practitioners, like Zhao Vuemnn (1719-1805), a native of Hangzhou, who wrote 12 books kept detailed records of scientific observations.

There is a medicine preparation hall, where veteran masters demonstrate for visitors such operations as pill shaping and slicing of crude drugs and give visitors the chance to use the hand tools, themselves (though none are there on the day I visit). I learn how the medical pellet originated from ancient alchemy by a Taoist priest.

I go through room after room of specimens of just about every element used in traditional Chinese medicine – from plants and rocks to animals, including gecko, snake, tiger, lion – with descriptions of what they are used for: leopard relieves rheumatism and pain; oil from fur seal to moisturize skin, clear wrinkles; Mastodon fossil for calming mind and settling fright.

In 1958, the pharmacy was turned into a Chinese medicine factory; it was restored and opened as a historical site in 1988 (a year which I note there seem to be a renewed respect and appreciation for ancient heritage). Most amazing to me as I finish exploring the museum, is that it is still a traditional Chinese pharmacy. As I leave the museum, and walk next door, there is an enormous salesroom with counters and white-coated pharmacists, jars of floating roots; I see patients waiting in a pleasant seating area where there are pools of water. Upstairs, in an attached modern building, are medical offices.

You need to spend at least one hour to go through the museum; it is simply not to be missed (www.hqytgyh.com).

As I make my way around the corner back to Hefang, I look beyond this ancient street at the McDonald’s, and my trip to the past is ended.

It’s my last day in Hangzhou and I realize I haven’t had much of a chance to shop (only kind of ironic, since everything in the U.S., it seems, is manufactured here). I look more closely at what is on sale here – there is fabulous stuff. After hearing so much about silk, I decide to buy some – silk pajamas for everyone.

I cycle back to the bike rental station – get back my 300 Yuan deposit, minus 50 yuan for 5 hours of bicycle rental ($7) – all of this by writing on a pad the number of hours I had the bike – we laugh.

As I walk back, parents and grandparents are waiting for children at dismissal from school. I watch a kind of parade as the students leave.

I make my way to a commercial center, just below the Radisson Hotel, where there is a Starbucks, as familiar in décor as the one our neighborhood, and enjoy a mocha Frappachino and a scone, watching the traffic and reading the newspaper.

On the way to the airport, I finally get to hear what the story of the Chinese “Romeo & Juliet” is about. My guide has made frequent mention of it, in connection with the legend of West Lake. It is a love story of a girl who pretends to be a man and falls in love. The boy realizes his friend is a girl and rushes to her home to ask for her hand in marriage, but she has been married off. I think this sounds more like “Yentl” than Shakespeare’s “Romeo & Juliet” but my guide has never heard of “Yentl.”

There is so much more to see in Hangzhou and Zhejiang Province than I could possibly do in the five days, and I look forward to returning. Several tour companies offer itineraries, such as a 10-day Zhejiang Highlights bus tour.

For more information about travel to Hangzhou, contact Hangzhou Municipal Tourism Commission, http://eng.hangzhou.gov.cn/

See also: Hangzhou: Ancient & Modern Come Together in China’s Popular Resort City

____________________

© 2016 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to [email protected]. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures