By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

The first stunning realization from the new exhibit at the American Merchant Marine Museum, “Liberty’s War,” is how vital the cargo ships, manned by civilian volunteers, were to winning World War II. The second is how dangerous this was – the convoys of merchant ships under near-constant attack by U-boats, Luftwaffe and kamikaze aircraft. Indeed, more than 9,500 merchant mariners lost their lives manning nearly 3,000 ships during the war. And finally, that the merchant seamen only received $5,000 compensation if they were killed or disabled in the war, and were not eligible for any of the GI Bill benefits the soldiers received. This probably tells the story more than anything else why their heroism is unsung and virtually unknown until a memoir of one engineer, Herman Melton.

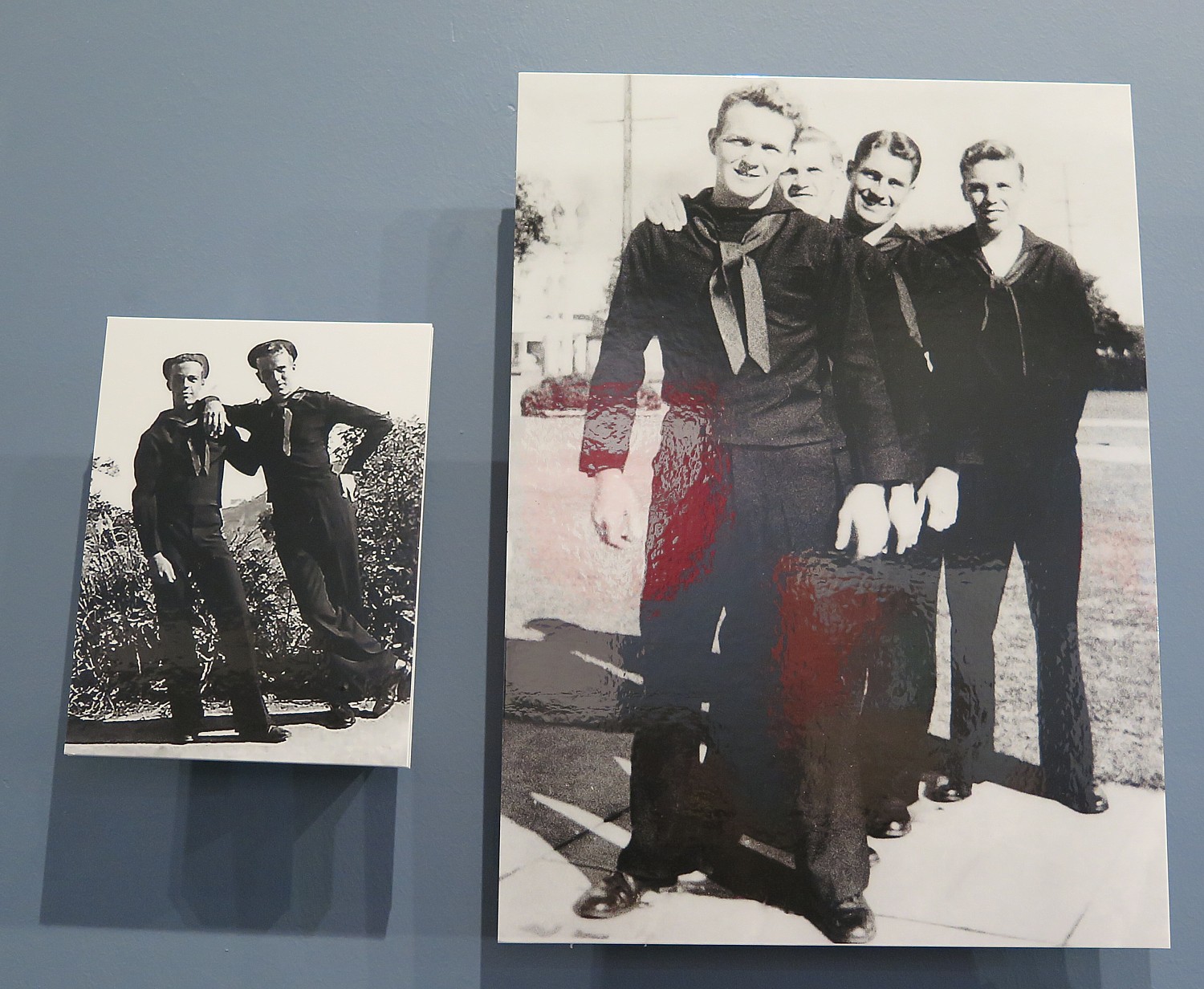

The new exhibit, which is on view through February 28, 2019, is based on the life and wartime experiences of Herman Melton, a graduate of USMMA’s class of 1944, as described in his memoir edited by his son, Will Melton, Liberty’s War: An Engineer’s Memoir of the Merchant Marine, 1942-45.. Herman Melton became an engineer, serving from 1942 to 1945 on so-called Liberty ships. His position on the ships – in the engineering room deep in the bowels of the ship– was particularly hazardous because enemy submarines would target the engine rooms as the most vulnerable part of a ship. But the men had to stay in their positions to give the ship a fighting chance for survival.

Indeed, the USMMA is the only military academy that flies the Battle Standard, in honor of the 142 of its students who died aboard merchant ships in World War II – tributes to them play in a tiny chapel-like room in the former Barstow mansion where the museum is housed. In all, more than 9,500 merchant mariners lost their lives in World War II.

The USMMA actually came into creation because of World War II – the need to staff the merchant ships was so critical that a four-year training program was compressed into 18 months.

The role of these Liberty ships – there were nearly 3,000 of the cargo ships between 1941 and 1945 – was critical to supply the war effort, to bring fuel and supplies to allies.

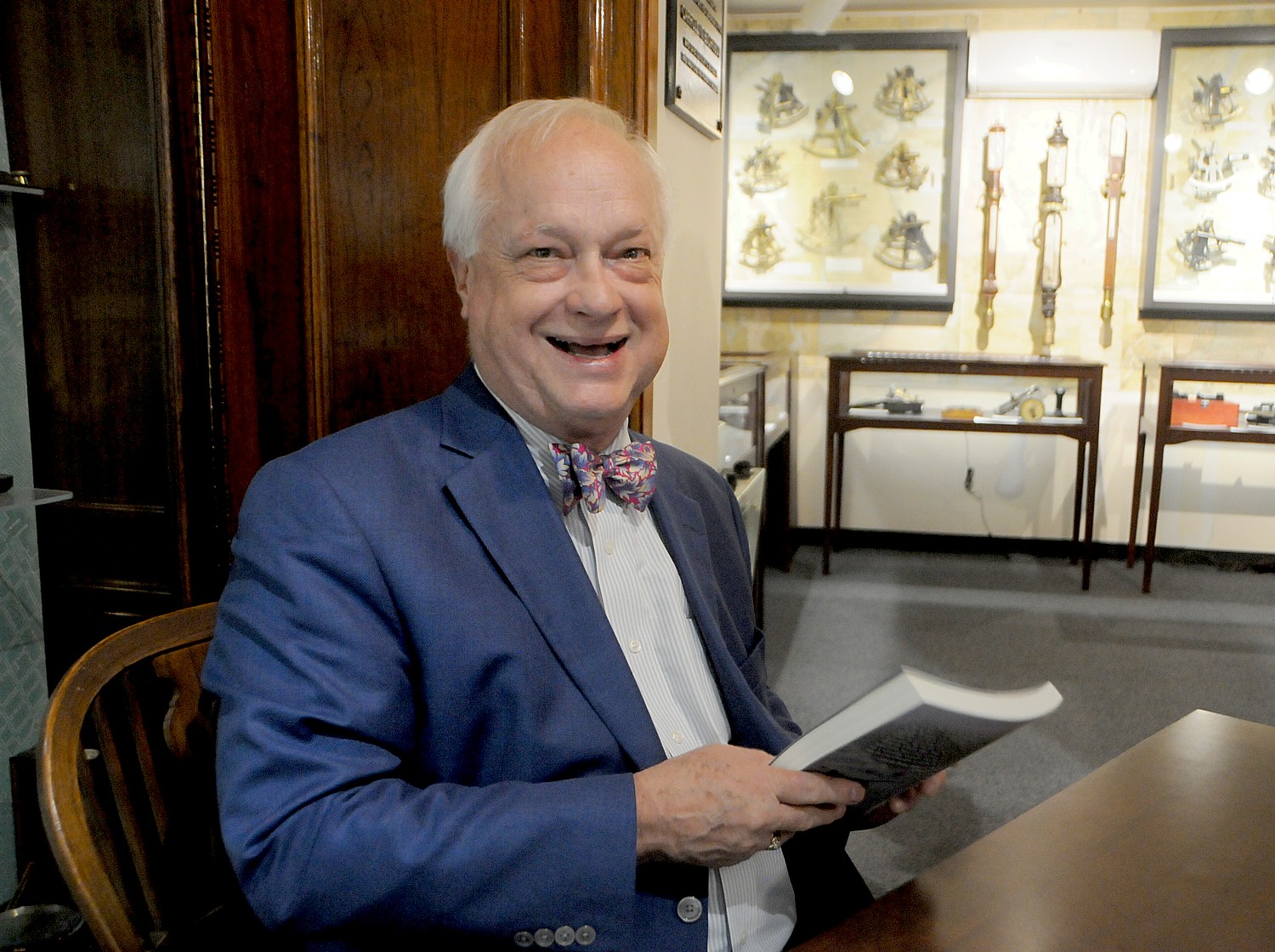

“They were an absolutely crucial link in the Allied supply chain that ultimately resulted in victory in 1945,” Joshua Smith, interim director of the American Merchant Marine Museum, writes in the exhibit’s brochure. “Too often that story gets ignored, but in the American Merchant Marine Museum’s latest exhibit, ‘Liberty’s War,’ the story of these valiant little freighters is told through the eyes of a young man from Texas, Herman Melton.”

Herman Melton was 89 years old when his son convinced him to write a memoir. As the exhibit notes reveal:

Melton faced combat in both the Atlantic and Pacific Theatres during World War II, always serving aboard Liberty ships, the slow but enormously useful vessels that carried the supplies that propelled the Allies to victory. During his time on convoy duty in three oceans, Herman entered combat at sea in some of the fiercest fighting with both the Germans and the Japanese. In the treacherous Murmansk run of 1942-43, Herman sailed as a Cadet-Midshipman as American and British merchant ships delivered urgently needed Lend-Lease supplies to the Soviet Union. Allied convoys faced German U-boats and Luftwaffe torpedo bombers operating at their peak efficiency, out of Norwegian bases. The result was that many Allied supply ships were lost, and many merchant mariners died while trying to supply the Russians.

During his January 1943 voyage across the Arctic Sea to north Russia, Herman’s Liberty ship, SS Cornelius Harnett, was attacked by torpedo bombers of Germany’s Coastal Air Group 406 based in Norway. Herman’s battle station called for him to carry ammunition and reload shell magazines for the U.S. Navy Armed Guard gun crew aboard the Harnett. The gunners helped to shoot down two of the four attacking aircraft, and their commander received the Silver Star from the U.S. Navy for his performance in the action. More than fifty years later, The Russian Embassy in Washington recognized Melton in a 1992 ceremony with a medal from the Russian Government for his service.

Herman again entered a deadly combat zone during the Allies’ invasion of the Philippines in the fall of 1944. Airmen of the combined Japanese army and naval air forces waged a do-or-die battle against American forces. Herman was now the Third Assistant Engineer aboard SS Antoine Saugrain in an Allied convoy steaming from New Guinea carrying specially-trained troops and super-secret anti-aircraft equipment. During an attack by Japanese torpedo bombers, the Saugrain took two direct hits before its Master gave the order to abandon ship off Leyte Island. Although the ship’s rafts and lifeboats could carry only a fraction of the more than 200 crew and soldiers to be rescued, all hands survived thanks to two U.S. Navy frigates dispatched to pick up men in boats and swimming in the water. After two more attacks by Japanese bombers, the Saugrain was sent to the sea bottom.

The exhibit also tells a love story, Herman’s wartime romance with Helen Dunn, his Kansas junior college sweetheart. Before departing for service in General Douglas MacArthur’s war in the South West Pacific, Herman and Helen were married in a saber ceremony in the Academy’s chapel in the old Chrysler mansion.

It is this personalization that makes the exhibit all the more poignant.

Melton’s memoir is being published by U.S. Naval Institute Press in September, to coincide with the museum’s exhibit highlighting Herman’s experiences battling both the Germans and the Japanese.

The “Liberty’s War” exhibit is illustrated with wonderful photos – personal as well as military – along with period uniforms, souvenirs of Herman’s wartime assignments and documents of his training as one of the first Engineer Cadet-Midshipmen of the USMMA, artifacts, ship models, and maps that let you trace Melton’s own harrowing journey as well as a superb documentary video you can watch in a small alcove.

In addition, there are remarkable paintings that were created by Jim Rae, who came to the exhibit opening at Kings Point from his home in Scotland to attend the opening reception, September 8. Rae’s drawings and paintings, which he has been making since he was a boy, are remarkably precise and exacting – he says he can complete one in the time it takes to watch a show over lunch.

Rae has spent his life at sea – first as a cabin boy in the British Merchant Navy and later enlisting in the Royal Navy. “It was while serving on various aircraft carriers that I took up painting once again.”

Rae says his subjects “are really quite specialized: not many people want a painting of the ‘Battle of the North Cape’ unless Granddad served in one of the ships taking part. I tend to concentrate on lesser known events, and the ‘little ship’ rather than the battleship and great battles.”

Barstow Mansion

The Merchant Marine Museum is housed in the former Barstow Mansion.

The Gold Coast mansion, harking back to the Gilded Age, is utterly stunning, William Slocum Barstow, the first mayor of Kings Point, made his fortune first, as a partner with Thomas Edison until he set out on his own, in 1901, one of the first electrical engineers. He founded many electric utility companies and was the man responsible for lighting the Brooklyn Bridge. He was very much involved in Great Neck community, even funding the bridge and overpass at the Long island Railroad to cut down on the fatalities when the train crossing was a street level, and he and his wife donated the funds for the Woman’s Club of Great Neck. The Mediterranean Revival-style mansion was Barstow’s main residence The Barstow Mansion was his main residence from 1 915 until the end of his life, in 1942, and then his wife’s until 1953 when it was sold to the Lundy family (of Lundy Restaurant fame). The architectural features – wood paneling, decorative ceilings – are breathtaking.

The American Merchant Marine Museum is located on the grounds of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, 300 Steamboat Road, Kings Point, NY 10024, fammm.us. Admission is free, and it is open to the public from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., Tuesday through Friday (closed during USMMA holidays and the month of July). It is highly recommended that you call (516) 726-6047 or e-mail museum@usmma.edu before visiting.

________

© 2017 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin , and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures