From the moment I hear the story of Sapelo Island, I am intrigued. The 50 remaining permanent residents are all descendents of Gullah-Geechee slaves. Access to the island is limited, and once there, “outsiders” who come on their own will have difficulty getting around – you’re not even allowed to take your own bicycle onto the island.

The number of permanent residents, once as many as 800, has steadily dwindled since the end of the Civil War and Emancipation, and now the community faces a dilemma: how to instill a sustainable economy that will keep the young people from migrating away, that does not cause this idyllic island to be overrun. Already, real estate developers are chomping at the bit.

The Gullah-Geechee are descendents of slaves brought 200 years ago from Africa and the West Indies to work the plantations. Their modest community of just 300 acres – the only part of the 16,000 acre island that does not belong to the State of Georgia – is in marked contrast to the RJ Reynolds mansion that has hosted presidents from Coolidge to Carter and continues to be an inspired venue for everything from destination weddings to academic conferences. Georgia and NOAA (National Oceanographic & Atmospheric Administration) also have research facilities on the island, in fact, at the Reynolds estate.

Sapelo Island – the fourth largest of Georgia’s barrier islands at 11 miles long and a mile wide – is owned by the State of Georgia, which uses it for research center for the state university, and a NOAA (National Oceanographic & Atmospheric Administration) research facility.

Unlike other barrier islands off Georgia – notably St. Simons, Sea Island and Jekyll Island – which have been turned into tourist havens, Sapelo Island has been insulated and almost entirely undeveloped. In fact, the only “law” governing the island is the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) – there are no police.

There is limited ferry service and limited transportation on the island all of which adds to its mystery and intrigue, and limited transportation around the island. You’re not even allowed to bring your own bicycle on the ferry from Meridien, but theoretically, you can rent on the island. Because of the difficulties of getting around the island, most people who visit join one of the (few) organized tours that are available.

And this is apparently the way the “locals” – the 50 actual residents of the island – like it.

We come to Sapelo Island with Andy Hill, who owns Private Islands of Georgia, a 2,000-acre territory of these back barrier islands encompassing eight private islands including Eagle Island where we stay. He owns a half-acre of property on Sapelo, giving him (and his guests) privileges to come and he keeps a truck at the dock. He takes his guests over with his pontoon, or you can rent a boat and Eagle Island guests sometimes come with their own boats.

The 20-minute ride to the island is very scenic and interesting. We get to see an alligator, roused from winter hibernation; ballast islands; Doboy Island.

We set out in Andy’s truck and quickly discover one of the island’s charms – no street signs and few paved roads and lots of live oak dripping with Spanish moss.

There are such incongruities to the island – shacks and dilapidated cars and trucks, only a couple of paved roads with the rest dirt or sand – contrasted with the splendor of the RJ Reynolds Mansion.

All of this makes the island that much more interesting: highlights of any visit include the Reynolds mansion home, the historic lighthouse (newly restored but you can’t climb it), and miles and miles of pristine beach. Nanny Goat Beach, a six-mile stretch, is among many beaches which are as private as private can get. There also are research stations operated by the state university.

And then there is Hog Hammock, which is the village established by the former slaves, where there is the beginning of a historic center.

In some ways, Sapelo Island calls to mind Cuba, the way cars and trucks are kept for an eternity and constantly repaired and the people and culture exist in isolation, and a book by Pat Conroy, “The Water is Wide,” about his experience as a teacher at a one-room schoolhouse on remote Daufuskie Island in South Carolina teaching black kids.

Reynolds Mansion

Start at the Reynolds Mansion, which gives context to Sapelo Island’s history, and only open for tours during specific hours.

The original Mansion was designed and built from tabby, a mixture of lime, shells and water, by Thomas Spalding, an architect, statesman and plantation owner who purchased the south end of the island in 1802. The Mansion served as the Spalding Plantation Manor from 1810 until the Civil War.

Spalding was a fairly remarkable man: he employed scientific farming techniques including crop rotation and diversification and was responsible not only for devising the formula for building tabby – a cement like construction material made from shells – but for cultivating Sea Island cotton and introducing the manufacture of sugar to Georgia. He also was elected to Congress and was an important local leader.

Spalding owned more than 350 slaves imported from Africa and the West Indies, but reportedly had misgivings about the institution of slavery, and had a reputation as “a liberal and humane master.” He utilized the task system of labor, which allowed his workers to have free time for personal pursuits. Slaves were supervised not by the typical white overseers but by black managers, the most prominent of whom was Bu Allah (or Bilali), a Muslim and Spalding’s second-in-command on Sapelo.

According to various biographies, Spalding was pro-Union (but anti abolition), and worked to win Georgia’s support of the 1850 Compromise.

Despite setbacks, Spalding’s prowess in agriculture and as a businessman (he was a founder of the Bank of Darien, advocated railroad and canal development in the region, and was active in state political affairs), enabled him to grow his plantation from 5,000-acres to eventually owning all of Sapelo Island’s 16,000-acres.

The mansion home was vandalized before and after the Civil War. After the Civil War, the former slaves, who began to earn cash for their labor, were able to buy land (that part of the story continues later when we meet Hog Hammock’s historian and local activist, Cornelia Bailey).

The entire island except for those communities held by the former slave families, was purchased in 1912 for $150,000 by Howard Coffin (founder of the Hudson Motor Company as well as the Cloister Hotel on Sea Island). Coffin restored the mansion, which then hosted visits of President and Mrs. Calvin Coolidge in 1928, President and Mrs. Herbert Hoover in 1932, and Charles Lindberg in 1929, who landed his plane on its small airstrip.

Tobacco heir Richard Reynolds, Jr. purchased the property during the Great Depression, in 1934.

Reynolds was an early environmentalist and founded the Sapelo Island Research Foundation in 1949. He later funded the research of Eugene Odum, whose 1958 paper The Ecology of a Salt Marsh showed the fragility of the cycle of nature in the wetlands; the research Odum did at Sapelo helped launch the modern ecology movement.

Reynolds’ widow, Annemarie Reynolds, sold Sapelo to the state of Georgia for $1 million, a fraction of its worth. The sale established the Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve, a state-federal partnership between the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The mansion is used today for groups – like destination weddings and conferences. The Reynolds Mansion can accommodate up to 29 guests in 13 bedrooms with 11 bathrooms. There is a minimum group size of 16 guests as well as a minimum 2-night stay.

The Mansion has marvelous architecture. The library has the original nameplates in many volumes from Reynolds’ private collection. Guests can use the Game Room’s billiards and table tennis. The ornately decorated Circus Room sports the wild animal murals of famed Atlanta artist, Athos Menaboni, whose work appears throughout the house.

The expansive grounds are particularly atmospheric with sculptures bathed in the sunlight filtering through massive live oaks.

Pathways link the Mansion’s grounds to the Atlantic Ocean where guests have use of a beachfront pavilion.

Mansion guests can explore the island on foot, bicycle, van or rented ocean kayaks. The lush forest envelopes you in a sea of green almost year round, and you are likely to sight whitetail deer, raccoon, opossum, wild turkey armadillo and other animals. The rare Guatemalan Chacalaca, imported to the island as a gamebird, runs wild in the forest, as do wild hogs and cattle, descendants of livestock that escaped from the farms of Sapelo’s early settlers. Sapelo is also a birders paradise. And of course, there are miles of unspoiled beach.

(Reynolds Mansion groups and conference participants are met at the ferry landing by air-conditioned vans; the vans are also available for the group’s use during their stay. Because of the unique ecological and archeological aspects of Sapelo, visitors have to obey very stringent and specific rules. For information and reservations, visit http://gastateparks.org/SapeloIslandReynoldsMansion or call 912-485-2299.)

Another interesting attraction is the 80-foot tall Sapelo Lighthouse which watches over Doboy Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. The five-acre lighthouse tract was sold to the federal government for $1 in 1808 by Thomas Spalding; the original lighthouse, 65 foot tall and topped by a 15-foot whale-oil lantern, was erected in 1820 for $14,500. Damaged several times by hurricanes over the years, it was eventually replaced and then deactivated in 1933. It was renovated in 1998 including a new spiral staircase, new lantern glass and light, and the spiral-striped exterior identical to the structure’s original paint scheme.

Today, its role is symbolic, since a steel tower outfitted with modern navigation aids was erected nearby as a replacement.

One of the enormous appeals of Sapelo Island for visitors are miles and miles of beaches. The main beach, Nanny Goat, has relatively easy access and bathroom facilities. We make our way with significant difficulty over some dirt roads, to one of the more secluded beaches at Cabretta Island where there are also campsites.

Hog Hammock

The highlight of our visit to Sapelo Island comes when we stop at Hog Hammock.

In its heyday, Hog Hammock would have had 800 residents; now the community of permanent residents has dwindled to just about 50, and only six children. Once there was a schoolhouse on the island; now the children go by ferry to the mainland.

All the descendents on the island trace back to 44 slave families – Bailey, Hogg, Walker, Spalding, and so forth. Many of the families were named for the owner (like Spalding); and many of the last names of enslaved populations on plantations originated from their job assignments. For example, the Bailey’s baled tobacco; Gardner’s tended the gardens; Grovner’s tended the groves; Hogg’s tended to hogs; Walker’s walked livestock.

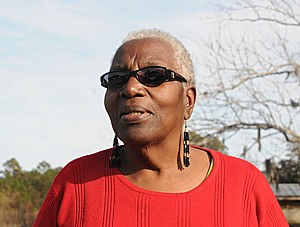

We get to meet the village historian and local activist, Cornelia Bailey, who has been accumulating artifacts in a small building which will serve as a museum but which does not seem open to the general public.

Cornelia Bailey’s ancestors first arrived on Sapelo in the 1790s, she tells us, and were here when the French came over. Beginning in 1802, a lot more came over, and after Thomas Spalding purchased the island, the number of Gullah-Geechee people grew to 800.

Just 50 of the community remain today.

“Everybody is still kin,” she says. She wants to revitalize the community so that it supports 150-200 people, but that will require jobs be created on the island.

The state of Georgia owns almost all of the island; Hog Hammock consists of just 300 of the 16,000 acres.

When the Civil War came, several slaves from Sapelo Island left and walked to Millersville, some walked to Thomasville (that’s a four-hour drive today).

The famous 54th Massachusetts, the black regiment – came through here and were responsible for burning Darien. “The blacks didn’t want to burn Darien,” Cornelia says. “the officers ordered them to give a lesson. The whites in the area still hold it against us.”

Did they know when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued? “We knew immediately because we had people here who served in Union forces.”

What happened here after slavery ended? I ask. “People in the north end were more independent. They didn’t want anyone telling them what to do. After being slaves for so many years. Rebellious people, took up arms against whites.

After the Civil War, she says, “for 35 years they didn’t work for any white man. They were jailed for refusing to be sharecroppers.”

“They planted for themselves They formed alliance and got their produce to market without a middleman, because until federal regulations, middlemen took all the profit.”

Many of the plantation owners lost their money because they supported the Confederacy. “Some buried it. Families were destitute Wives sold land. Some of my people who worked for federal government could pay 50 cents an acre.”

After 1870 and Reconstruction, she tells us, many of the former slaves ended up owning land; a lot worked for the federal government, earning cash money. They purchased land from their former owners – apparently being given handwritten slips of paper to show their ownership.

At one time, there were five different communities in five different parts of the island.

When Reynolds bought the island, he had the idea to develop it much as Jekyll Island and Sea Island had been developed, and wanted to consolidate all the Gullah-Geechee residents in one community from the five different communities.

“He said it was for wildlife preservation. But he wanted to develop north end,” she says.

“Everyone got a deed for land here but were cheated out of land in the north [of the island],” she tells us.They claimed that because the former slaves did not have the King’s grant, they could not prove their ownership.

Cornelia manifests the proud, independent streak of her ancestors, and is suspicious of outside developers who might come in and take over.

“Come and enjoy what we eat – seafood dishes. We’re cordial but don’t want outsiders to stay.”

Bailey wants to make the community economically viable but is not keen on promoting the obvious cash-cow, tourism, because that would mean opening the floodgates to outsiders.

The Sapelo Island, Georgia (SIG) Community Improvement District (CID) is working to create a more walkable, bikeable and livable rural environment, and there is a Small Business Incubator which is hoping to spur the successful development of entrepreneurial companies.

I get the impression they don’t really want the outside world. Instead, her approach to economic revitalization is to revitalize agriculture.

Meanwhile, the community has been fighting back real estate development, and discourage locals from selling their property to outsiders.

Instead of opening floodgates to outsiders, Sapelo Island hosts a once-a-year festival, Sapelo Days Festival, on the third Saturday in October, when the island invites back all those who used to live here, whose families trace their roots here, and anyone else who is curious or who wants to be immersed in Gullah-Geechee culture.

Family of residents and those who have moved off the island start arriving Thursday; on Saturday, boat loads come, by 7:30-8 pm, they are gone.

“It’s a cultural day. People have their best manners, best foods,” she says, sounding like the grandmother who loves to have their grandchildren for a day and then send them back to the parents.

The festival is a fundraiser that helps support the Sapelo community.

Before we leave, we stop into Cornelia’s general store, where you can purchase a cookbook she wrote (there isn’t much else in the store). But you can see a display about Sapelo Island’s most famous resident, Cornelia’s nephew, Allen Bailey, who played for the Miami Hurricanes and the Kansas City Chiefs.

The Gullah-Geechee community extends from southern North Carolina down to northern Florida. The Gullahs achieved a victory in 2006 when the U.S. Congress passed the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Act that provides $10 million over 10 years for the preservation and interpretation of historic sites relating to Gullah culture. The Heritage Corridor project is being administered by the US National Park Service with extensive consultation with the Gullah community.

Special Programs

The State of Georgia offers guided bus tours of Sapelo Island on Wednesdays (8:30 – 12:30) and Saturdays (9 – 1) throughout the year, Fridays (8:30 – 12:30) June 1 through Labor Day; and an extended tour on the Last Tuesday (8:30 – 3) of each month March through October. Public tour reservations can be made by calling 912-437-3224 (adults/$15; Children (6-12)/ $10; ages 5 and under/free).

The Visitors Center is open Tuesday – Friday 7:30-5:30, Saturday 8-5:30, closed on Sunday and Monday. Group tours for 10-40 people are offered on Tuesdays and Thursdays (8:30-3) throughout the year, and Fridays (8:30-12:30) from Labor Day to the end of May. Those tours can be arranged by calling the Education Office at 912-485-2300. Tickets for public and group tours of Sapelo Island can be purchased at the Visitor Center. T-shirts, books, and videos are also available for purchase.

The Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve (www.sapelonerr.org) work closely together managing the island’s resources. Guided interpretive tours of the mansion, slide shows of the island, interpretive beach walks and other ecological or scientific presentations can be arranged through the Reynolds Mansion conference coordinator with advance notice. Special outings, cookouts, picnics and other group activities are also possible with advance notice when booking your reservations. (The Reynolds Mansion on Sapelo Island, P.O. BOX 15, Sapelo Island, Georgia 31327, 912-485-2299).

Getting to Sapelo Island

One of the principal ways of accessing Sapelo Island is aboard the Georgia Department of Natural Resources ferry which serves visitors and residents alike. The $10 per person round-trip fee for the half-hour ride is paid at the Meridian ferry dock. (You are not allowed to bring bicycles, beach chairs or a host of other things.)

The mainland ferry dock, visitor center and parking areas are located in Meridian, Georgia, 8 miles east of Darien. From I-95, take exit 58 on GA HWY 57 to HWY 99.

Sapelo Island Visitors Center, 1766 Landing Rd SE, Darien, GA 31305, 912-437-3224, sapelovc@darientel.net, www.sapelonerr.org/visitor-center.

See also:

Eagle Island, One of ‘Private Islands of Georgia’ Offers Rarest Luxury: Time Together

_______________________________

© 2015 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit www.examiner.com/eclectic-travel-in-national/karen-rubin, www.examiner.com/eclectic-traveler-in-long-island/karen-rubin, www.examiner.com/international-travel-in-national/karen-rubin, goingplacesfarandnear.com and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures.