by Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

I was surprised to discover during a Global Scavenger Hunt mystery tour around the world in 2019 that I was actually on an odyssey of the Jewish Diaspora. It wasn’t my intention or my mission but everywhere we went (we only learn where we are next going when we are told to get to the airport), I found myself tracing a route set by trade (and permitted occupations), exile and refuge.

It started in Vietnam and then just about every place we touched down: in Yangon, Myanmar, where I visited the last synagogue in that country (it’s a historic landmark and still serves a handful of congregants); in the ancient desert city of Petra, Jordan, I learned of a connection to Moses and the Exodus miracle (the first Diaspora?); in Athens, where I discovered a synagogue, serving a Jewish community that had existed in Athens at least since the 3rd C BC and possibly as early as 6th C BC, near where the world’s first “parliament” would have been.

Then on to Morocco, a country that has just established full diplomatic relations with Israel. The news was particularly interesting to me because Morocco has a long-standing tradition, going back centuries of welcoming Jews, harboring Jews and even today, protecting the cemeteries and the few remaining synagogues, as I discovered for myself during the Global Scavenger Hunt:

Marrakesh

Before it gets too dark, we make our way through the souks to find the Mellah, the Jewish Quarter and the synagogue (which happens also to be one of the scavenges on our around-the-world mystery tour).

We weave through the maze of alleys – asking people who point us in a direction (just as we are supposed to do under the Global Scavenger Hunt rules) – a kindly fellow leaves his stall to lead us down narrow alleyway to Laazama Synagogue, which is still a functioning synagogue but also serves as the city’s Jewish Museum.

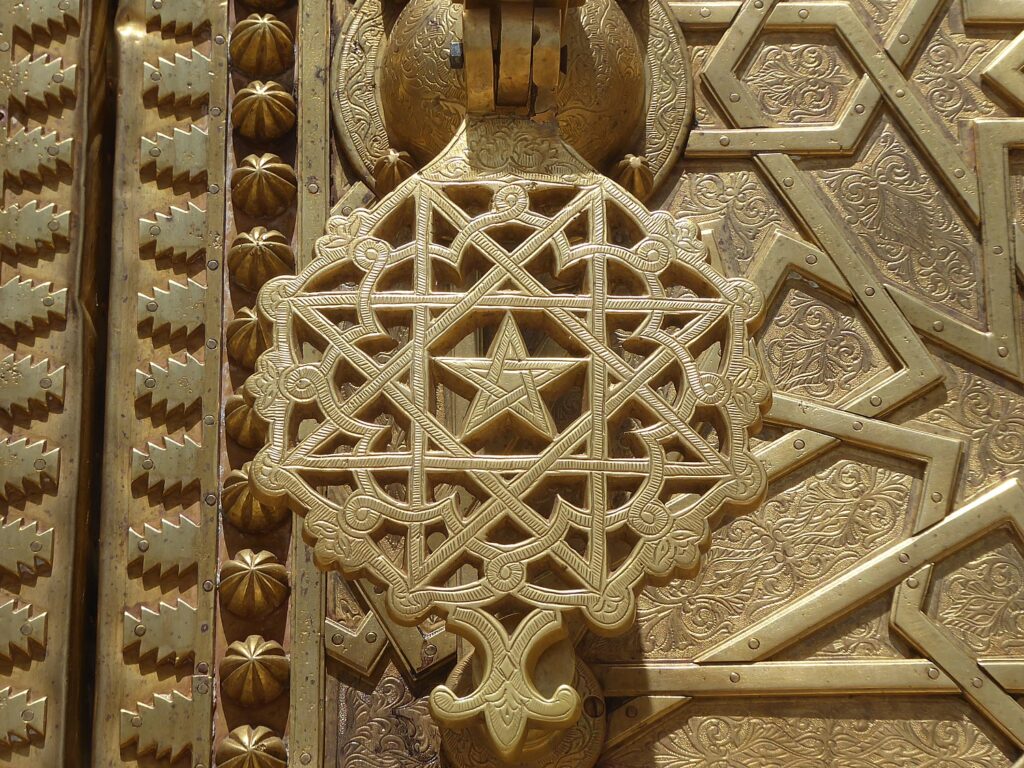

After Jews were expelled from Spain by Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand in 1492, Rabbi Yitzhag Daloya came to Marrakesh, notes describe. He became president of the court and head of the “deportee” community in Marrakesh and founded the “Tzlat Laazama,” Synagogue of Deportees”, shortly after his arrival.

But the Moroccan Jewish community is much older than the Spanish Inquisition, actually dating back to King Solomon and the Roman period. Marrakesh was founded in 1062 by Joseph Ibn Tasifin, ruler of the Halmorabidim, who allowed Jewish settlement in the city. The Jewish community was “renewed” in 1269, headed by Rabbi Yahuda Jian, originally from southern Spain. The Atlas Jews remained the majority of the community even after the Jews from Spain and Portugal settled in Marrakesh.

The situation changed in the 16th century when Marrakesh became a major center for Marranos (secret Jews) who wished to practice Judaism openly. Spanish and Portuguese Marrakesh Jews lived in their own neighborhoods until all local Jews, some 35,000, were collected by order of the King, in 1557, and resettled in the Mellah (a walled community). In the 19th century, the population increased in the Mellah after refugees from the Atlas Mountains arrived, becoming the largest Jewish community in Morocco. At one time, there were 40 synagogues here.

The synagogue is beautifully decorated with tile, a courtyard ringed with study rooms, a music room, living quarters. There is a video about history of Jewish community in Marrakesh. The photos on the walls are interesting – the faces of the Moroccan Jews are indistinguishable from the Arab Moroccans.

Moroccan Jews have largely left the country – the Moroccan Jewish Diaspora counts more than 1 million members in four corners of the world, “a diaspora that continues to cultivate ties to their homeland, Morocco.” (Morocco’s diplomatic and trade alliance with Israel should help.) Indeed, we come upon a woman with her sister-in-law and mother who left Marrakesh first for Casablanca and now lives in Paris; her brother is still a member of the synagogue’s leadership – she shows us his chair. Her grandfather is buried in the nearby Jewish cemetery.

From the synagogue, we walk to the Jewish cemetery, Beth Mo’ed Le’kol Chai, which should have been closed, but the guard lets us in.

Founded in 1537, the cemetery spans 52 hectares and is the largest Jewish burial site in Morocco, with some 20,000 tombs including tombs of 60 “saints” and devotees who taught Torah to the communities of Marrakesh and throughout Morocco.

The arrangement of the graves is “unique” to the city of Marrakesh. There is a children’s section, where 7000 children who died of Typhus are buried; a separate men’s section and a woman’s section while around the perimeter are graves of the pious, the judges and scholars of the city who are believed to provide protection for all those buried.

See: UNRAVELING MARRAKESH’S OLD CITY MAZE BEFORE TACKLING THE GLOBAL SCAVENGER HUNT 4-COUNTRY CHALLENGE

Fez

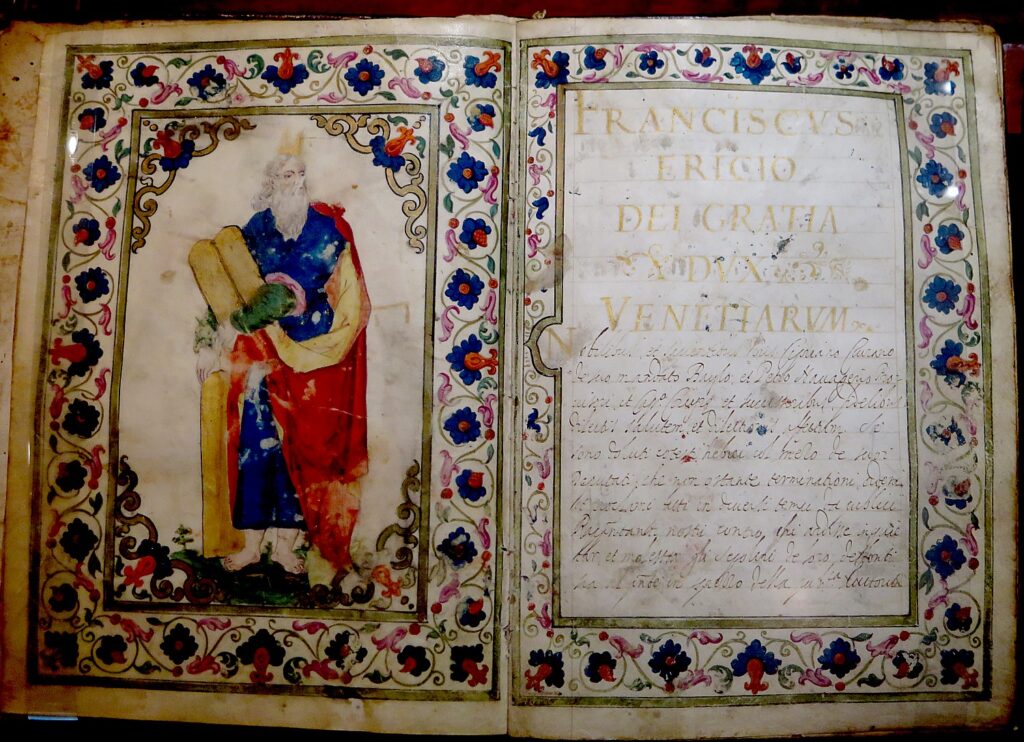

Cautioned that the Fez is a complete maze that requires a local guide, we set out with Hamid, theoretically licensed by the local tourist office. At our first stop, at the golden doors to the palace, he relates how Jews made refugees when expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492 were invited by the sultan to settle in Fez in order to develop the city, and settle the nomadic Berbers. The sultan gave them land adjacent to the palace and promised protection. To show appreciation, the Jewish community created ornate brass doors for the palace with the Star of David surrounded by the Islamic star.

He takes us to Fez el-Jdid (the “new part of the city”, which is still a few hundred years old) to visit the Mellah -the Jewish Quarter. The oldest Jewish Quarter in Morocco, the Mellah of Fez dates back to 1438, though very few Jews live here today, most having moved to Casablanca, France or Israel; there are some 80 Jews left in Fez, but live in the new city, Ville Nouvelle.

This community continued even into World War II, when the Sultan gave Jews citizenship and protected them from the Nazis. Indeed, Morocco’s Jewish population peaked in the 1940s but since the 1950s and 1960s, following the establishment of Israel, shrank to fewer than 5,000 today.

Hamid leads us through winding narrow alleyways to the Ibn Danan synagogue. The synagogue was restored in 1998-99 with the help of UNESCO, American Jews and American Express. From the top floor, you can see the Jewish cemetery.

Nearby is al Fassiyine Synagogue, which a plaque notes, “belongs to the Jews (Beldiyine) Toshabirg, native Jews who lived in Fez before the arrival of the Megorashimns, the expelled Jews from Spain in 1492. The building, covering 170 sq meters, was built in the 17th century. It includes a small entrance hall which leads to a prayer hall housing some furnished rooms on the mezzanine level. It has been used successively as a workshop for carpets and then a gym. Despite these different uses and the degradation of its state, it still keeps its original aspect.”

The synagogue was restored in 2010-2011 through the efforts of Simon Levy, former general secretary of the Judeo-Moroccan Heritage Foundation, the Jewish community of Fez, Jacques Toledano Foundation and the Foreign Affairs Ministry of Germany.

Morocco’s Islamist Prime Minister Abdelilah Benkirane inaugurated the reopening of the historic synagogue on February 13, 2013, in which he conveyed the wish of Morocco’s King Muhammad VI that all the country’s synagogues be refurbished and serve as “centers for cultural dialogue.”

Hamid tells me that an adviser to the King and the ex-minister of Tourism were both Jewish.

The tourism minister had a lot to do with putting Morocco on the map as an international tourist destination. The king, who studied at Harvard, in 2000 set a goal of 10 million tourists.

“Morocco has no oil or gold. It had no highway or airport and didn’t exist except for hashish,” Hamid says. “The king opened Morocco to foreign companies, giving them five years duty-free. They were drawn by a peaceful country, a gateway to Africa. Foreign investors rebuilt the road to Marrakesh, turning it into an international city for the wealthy, like Europe.” Fez also seems to be benefiting – there is lots of restoration and new construction, at Riad el Yacout where we are staying.

As we weave through the alleyways, he shows us the indentation on the doorposts of houses where a mezuzah would have been placed, now the home of Muslims (Jews apparently weren’t evicted from these homes, rather, they moved to the suburbs; what Jews remain in Fez live in the new city, Ville Nouvelle).

See: GLOBAL SCAVENGER HUNT: ENTRANCED BY THE MYSTIQUE OF FEZ, MOROCCO

Gibraltar

Arriving in Gibraltar from Morocco, it is almost culture shock to instantly find yourself in a British Brigadoon – back in time. It is all the more surprising to learn of Gibraltar’s sizeable Jewish community in a population of only 36,000.

I wrongly assume that Gibraltar’s Jewish heritage goes back to the Spanish Inquisition – after all, it is but steps away from Spain – but Gibraltar’s Jewish community actually traces the same route that I have come, from Morocco. Jews were readmitted to the tiny peninsula on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula after the British took the territory from Spain in 1704. By the mid 18th century, the community comprised about one third of the Gibraltar’s population. Today, the Gibraltarian Jewish community numbers around 600, many of whom are Sephardim whose roots go back to Morocco. (https://jewish-heritage-europe.eu/united-kingdom/gibraltar/)

On The Rock, which is literally the plateau on top of Gibraltar where many of the historic and nature sites are found, you can follow a trail to Jew’s Gate which leads to the Jewish cemetery tucked away behind trees that was in use up until 1848; it offers “a fascinating piece of history that reflects the important role the Jewish people have played in molding Gibraltar’s history”). I find four synagogues:

Sha’ar Hashamayim – Esnoga Grande or Great Synagogue, the main synagogue in Gibraltar, originally built in the 1720s, was destroyed during heavy storms in 1766 and rebuilt in 1768, then destroyed again by gunfire during the Great Siege of Gibraltar, May 17, 1781, and reconstructed again, after a fire in 1812; Ets Hayim – Esnoga Chica or The Little Synagogue, dating from 1759; Nefutsot Yehoda – Esnoga Flamenca or Flemish Synagogue, opened in 1799 and rebuilt after serious damage from fire in the early 20th century, in the Sephardic style; and Esnoga Abudarham – Abudarham Synagogue, established in the early 19th century by immigrants from Morocco.

From Gibraltar, I basically walk from my hotel, The Rock, into Spain, where I take a bus to Seville for the next part of the Global Scavenger Hunt and my Jewish Odyssey.

See: GLOBAL SCAVENGER HUNT: A DASH THROUGH GIBRALTAR REVEALS A MODERN-DAY BRIGADOON

Next: Jewish Odyssey Continues in Seville

______________________

© 2021 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to [email protected]. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures