By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

On a grand night at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Uniondale, Long Island, five of the Apollo astronauts, including three of only 12 men who have ever walked on the moon, and two flight directors who controlled the Apollo missions, reflected on their experiences. It was an epic event in a year of events at the museum marking the 50th Anniversary of the first man to walk on the moon, inspiring interest in space science, which will climax on July 20 at the exact moment when Neil Armstrong made his “giant leap for mankind.”

The Cradle of Aviation Museum has special meaning to the astronauts, many of whom have come to the museum over the years to give talks and participate in events. Not only is it home to one of the world’s most extensive collections of Lunar Modules,(LM-13, LTA-1), Lunar Module parts and Lunar Module photos and documentation, but it also is home to the engineers of Grumman Aerospace Corporation that designed, built and tested the Lunar Modules between 1961-1972 which successfully landed 12 men on the moon between 1969-1972.

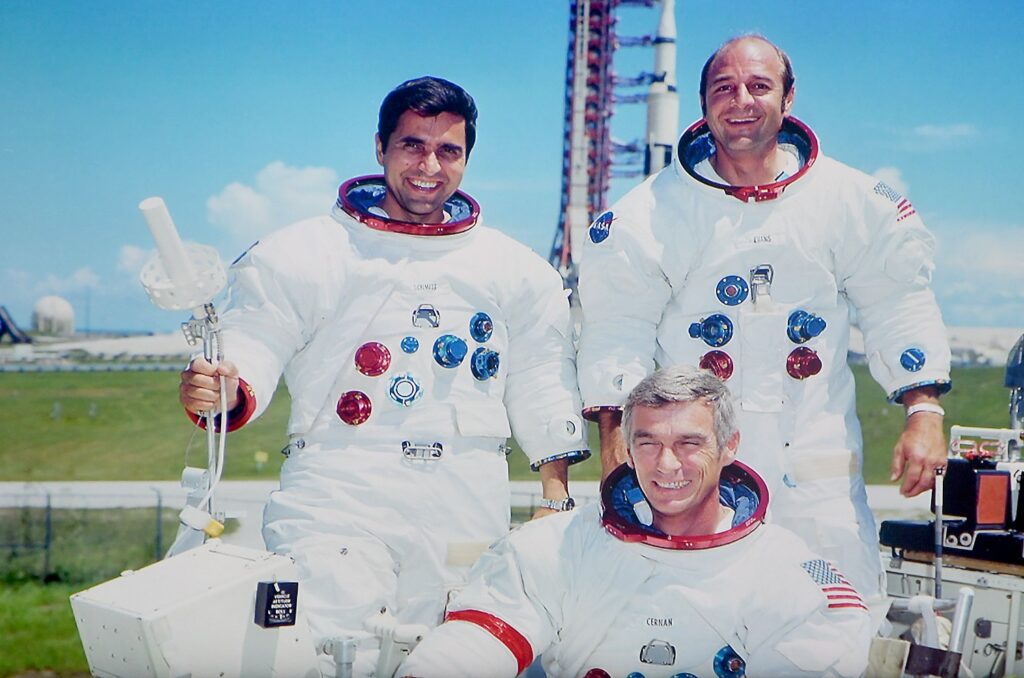

Here are highlights from the discussion of Walt Cunningham (Lunar Module Pilot, Apollo 7), Rusty Schweickart (Lunar Module Pilot, Apollo 9), Fred Haise (Lunar Module Pilot, Apollo 13). Charlie Duke (Lunar Module Pilot, Apollo 16), Harrison Schmitt (Lunar Module Pilot, Apollo 17) and Apollo Flight Directors, Gerry Griffin and Milt Windler.

Rusty Schweickart was the first to pilot the Lunar Module, testing the craft on the Apollo 9 mission in 1969 before it was used on the moon in Apollo 11. He was one of the first astronauts to space-walk without a tether, and one of the first to transmit live TV pictures from space. He is also credited with development of the hardware and procedures which prolonged the life of the Skylab space station.

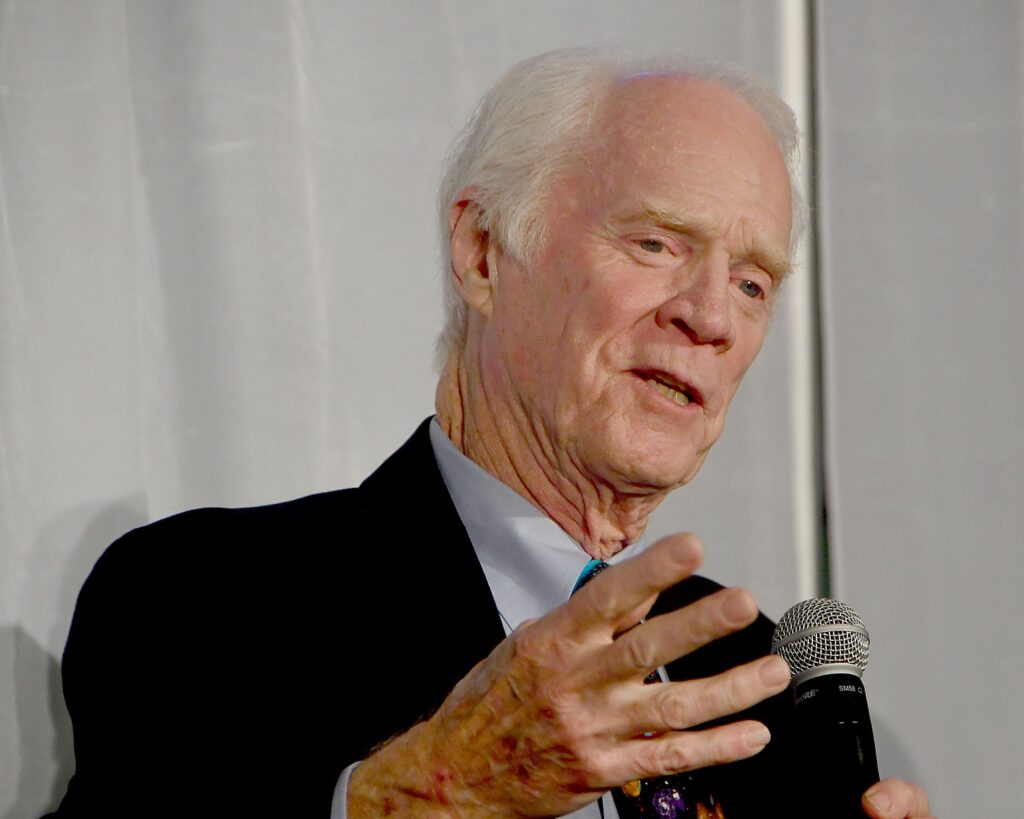

Schweickart reflected on a moment when he was essentially stranded in space. “I turned around and looked at earth, brilliant blue horizon. There was no sound – I was floating inside my suit which was floating. Just hanging out looking at earth, completely silent. My responsibility at that moment was to absorb: I’m a human being. Questions floated in: how did I get here, why was I here. I realized the answer was not simple. What does ‘I’ mean? ‘Me’ or ‘us’. Humanity – our partnership with machines allowed humankind to move out to this environment. 10,000 years from now, it will still be the moment when humanity stepped out to space. While we celebrate something we were part of, it’s one of the events in human history, , that if we don’t wipe ourselves out, we will still have this unique moment in time when life moved out to outer space.”

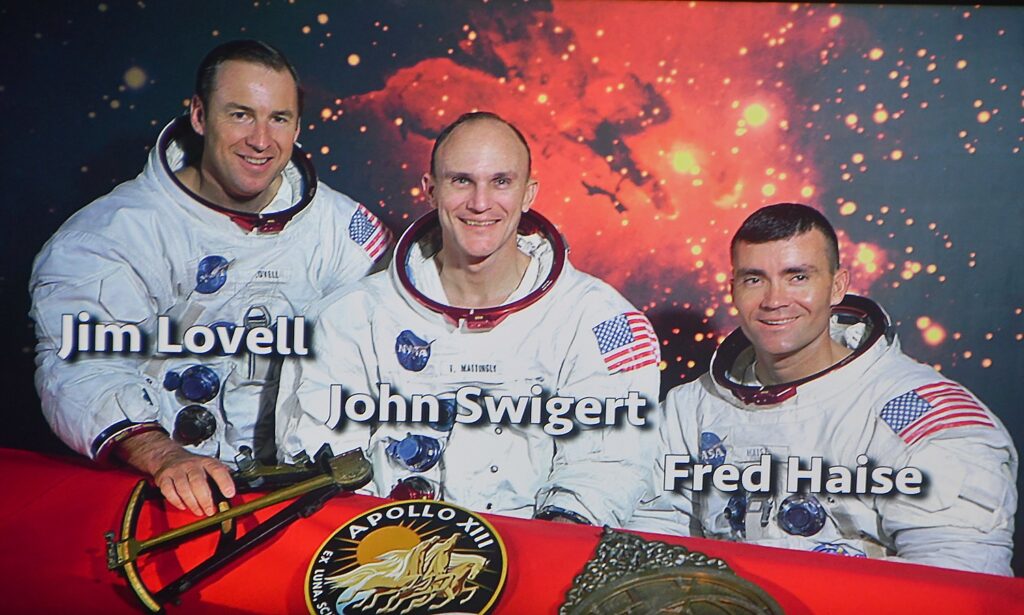

Fred Haise, the Lunar Module Pilot on the Apollo 13 mission, would have been the 6th man to walk on the moon. After the Apollo program ended in 1977, he worked on the Shuttle program, and after retiring from NASA, worked for 16 years as an executive for Northrop Grumman Corporation.

Haise reflected that when JFK made his challenge to go to the moon before the end of the decade, he thought this was mission impossible based on where the technology was. “I saw nothing at hand that would have accomplished that. By then, there was just Alan Shepherd who went up and down, the rockets were invented by Germans in World War II.”

When the disaster struck the Apollo 13 – an oxygen tank exploded, crippling the Service Module which supplied power and life support to the Command Module, he reflected, “We weren’t afraid. All of us in the program did the best we could. We were aware of the problems. Everyone was willing to pay the price to make the mission successful.”

The situation was not immediately life-threatening . ”Clearly we had lost one tank. I was sick to my stomach with disappointment that we had lost the moon. It took us almost an hour to stop the leak in the second tank. “

The Lunar Module was pressed into service as a literally lifeboat and tugboat – a role never anticipated for it.

“The LM bought time. I was never worried. Not sure how it would operate past the two days. Nothing had been damaged in the LM, so I knew we had a homestead we could operate from, and people on the ground were losing a lot of sleep working through the challenges. We never really got to the cliff we were about the fall off.”

Despite great hardship caused by limited power, loss of cabin heat, shortage of cooling water and the critical need to make repairs to the carbon dioxide removal system, the crew returned safely to Earth. It was hailed as the most successful failure.

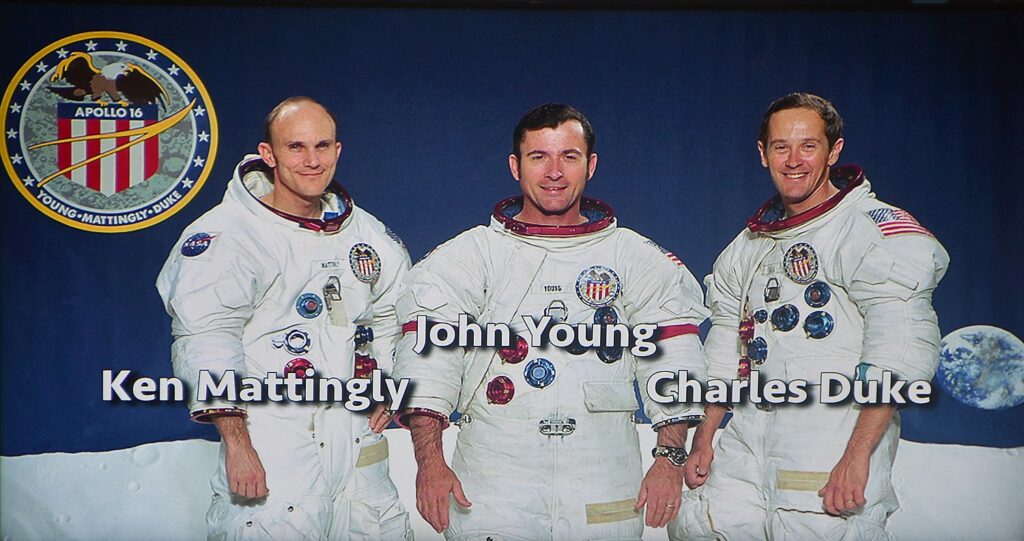

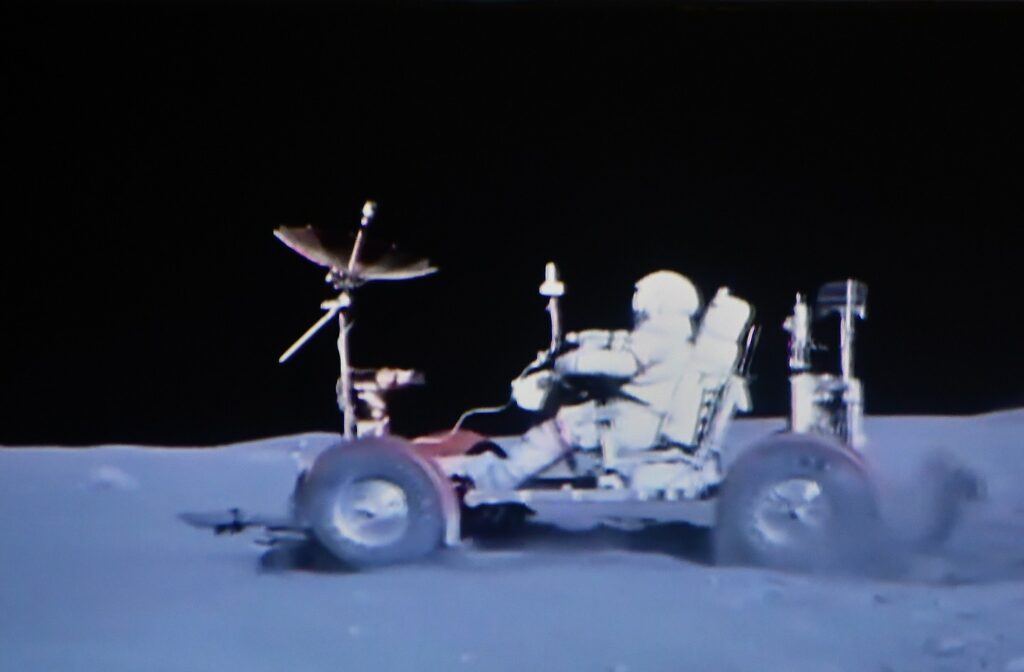

Charlie Duke (Lunar Module Pilot, Apollo 16, the 10th person to walk on the moon and the youngest, at 36 years old), reflected “Driving over the surface of the moon, we didn’t have TV. I was the travel guide for mission control, 250,000 miles away. So I narrated, ‘Now we’re passing on the right…’ – giving a travelogue – as we drove from point A to point B, and I was taking pictures. My job was to get us A to B and describe for mission control what seeing while John was driving…

“The rover did tremendously well, it revolutionized lunar exploration. Prior, we had to walk everywhere, not the easiest thing. Thankfully the rover was a revolution to see so much. Say to all the Grumman folks here who worked on that, you guys built a great machine. We shared the moon speed record because the odometer only went to 17 mph. Three rovers are up there – if you want an $8 million car with a dead battery.”

Harrison Schmitt (Lunar Module Pilot, Apollo 17) was also a former geologist, professor, US Senator from New Mexico. He was the lunar module pilot on Apollo 17, the final manned lunar landing mission. He was the first scientist and one of the last astronauts to walk on the moon – the 12th man and second youngest person to set foot on the moon.

“The thing about our valley [where the mission explored], Apollo worked in a brilliant sun, as brilliant as any New Mexico sun, but the sky was absolute black. That was hard to get used to. We grow up with blue skies. I never felt comfortable with black sky. But in that black sky was of course that seemingly small planet Earth, always hanging over the same part of the valley. Whenever I was homesick, I would just look up – home was only 250,000 miles away.”

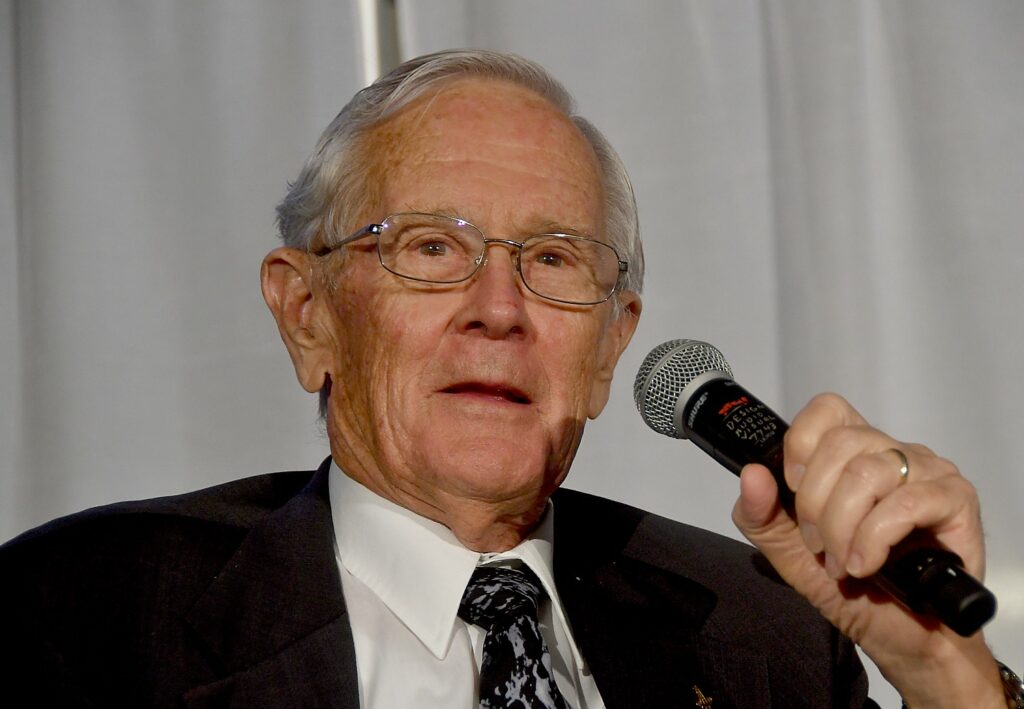

Milt Windler was one of the four flight directors of Apollo 13 Mission Operations Team, all of whom were awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Richard M. Nixon for their work in guiding the crippled spacecraft safely back to Earth. Formerly a jet fight pilot, he joined NASA in 1959 during Project Mercury. Windler also served as a flight director for Apollo 8, 10, 11, 14, 15 and all three Skylab missions. After Apollo, he worked in the Space shuttle project office on Remote Manipulator Systems Operations until 1978. He is the recipient of the NASA Exceptional Service Medal.

Reflecting on the Apollo 13 mission, he said, “It is a common misconception that flight control was one person all 15 days of a mission. But missions were divided into distinct phases – launch, lunar descent, EVA, rendezvous – and there were teams for each. Each team simulated, practiced problems. One of the things that worked well on Apollo was anticipating what would happen. After a flight, we would discuss lessons learned, to come up with improvements. By the time of Apollo 13 developed a real serious problem, we were a finely honed machine.”

Gerry Griffin joined NASA in 1964 as flight controller in Mission Control during Project Gemini. In 1968, he was named a Mission Control flight director, for all the Apollo manned mission. Gerry’s “Gold” team conducted half of the lunar landings made during Apollo 14, 16, and 17, and would have conducted the landing of Apollo 13 but played a key role in the safe return of the astronauts. Later Griffin played several Hollywood roles in movies including “Apollo 13, “ “Contact”, Deep Space” and “From the Earth to the Moon,”, as a consultant and even an actor.

The astronauts reflected on the “perfect storm” of forces and factors that resulted in the incomparable space program that put a man on the moon within a decade – Griffin, quoting Neil Armstrong, said you needed four things: threat, bold leadership, public support and resources. “He said that most of the time, those are out of sequence with each other – you may have the threat but not the resources. It was a perfect storm when Apollo happened”: the threat from the Soviet Union taking mastery of space frontier; a balanced budget not yet weighted down by national debt; bold political leadership and public support. “You had the resources and human resources, primarily from World War II from the aviation industry, with Grumman part of that.

“If it hadn’t been Apollo, it would have been something else. When the Soviets launched Sputnik and then Gagarin [became the first man in space], the threat was clear, and everything else fell into line. I think he’s right. Nowadays, we have a threat now – China – those guys are good. There is a technological threat now, and could be more later. Leadership? Draw your own conclusion. Resources? We haven’t had them. Public support? … But I’m an optimistic. If we are going to make 2024 – that’s awful tight, but I was like Fred, I didn’t think we could land on moon in the 1960s, but we did. Maybe if things line up better, we could do it by 2024, if not 2028.”

Asked why we haven’t been back to the moon, Schweickart said, “You need to be young, innovative, not an aging bureaucracy….

“You need technological, political courage. The moon was in exactly the right place. The next steps are not quite that easy . There is a debate between going back to the moon or on to Mars that has raged for years and still does. There’s not the same opportunity that we had at that time. In many ways, the most important thing in terms of a sense of challenge, moving out, moving forward is one of age. Bureaucracy – corporation or government – where the average age increases every year, you’re cooked.”

They are much more encouraged by private enterprise taking over space exploration. “You don’t see much about Blue Origin and Jeff Bezos, but we will. When you see [Elon Musks’s] SpaceX launch Falcon 9, Falcon Heavy and bring back two stages that land in formation, and the cameras show all these kids, 20 years old, hooping and hollering, they did it! That’s what it takes. NASA used to be that way. Part of the real juice in space exploration is encouraging private activities in space. That today is where most of the juice is, getting young people involved is the key, giving them the opportunity. Jeff Bezos says it well. His fundamental motivating, commitment to space is to reduce the cost so more and more can take part and therefore dramatically increase the quality and opportunity for innovation. As the cost of getting to space drops, the creativity will dramatically increase. That’s where it’s at in the future.”

Walt Cunningham a fighter pilot before he became an astronaut, in 1968, he was a Lunar Module Pilot on the Apollo 7 mission. He’s also been a physicist, entrepreneur, venture capitalist and author of “The All American Boys.”

“Our society is changing,” he reflected the next evening when he gave a lecture at the museum. “Back when Apollo was a story of exploration and adventure – my generation – we had te opportunity and courage to reach around the moon and to the stars. We were willing to take risks, didn’t shy from unknown. In those days, it seemed normal to do what we were doing – exploring the next frontier. Today, the entire world takes pride in this greatest adventure.”

Sixty years ago, “the main drive was beating Russians to the moon. They beat us around earth. When that started a technological fight to finish, not a single American had been in orbit, but Kennedy was willing to take the risk – not just technological, but human, economic, political. He took the initiative, the leadership. Today, that goal is history. Fifty years ago, we never thought of failing –we had fighter pilot attitude – common dream to test limits of imagination, daring.

“That attitude enabled us to overcome obstacles. Any project as complex as Apollo required resources, technology, but most importantly, the will. Driven by the Cold War, all three came together in the 1960s and we went to moon. Think of it: only three generations separated man’s first flight off the earth and man’s first orbit around the earth. Only three generations.”

Somewhat ironically, on the same day as the astronauts were assembled at Cradle of Aviation, President Donald Trump was contradicting Vice President Mike Pence and his own policy, which said that the US would be back on the moon by 2024. Trump called another moon mission a waste of money which should be spent, instead to go to Mars.

Trump also has called for the creation of a Space Force, a new branch of the armed forces, effectively undoing the spirit of international cooperation in space exploration to advance human knowledge, with a shift toward militarizing space.

Cradle of Aviation Museum, Charles Lindbergh Blvd, Garden City, NY 11530, General (516) 572-4111, Reservations (516) 572-4066, http://cradleofaviation.org.

See also:

Long Island’s World-Class Cradle of Aviation Museum Hosts Special Events for 50th Anniversary of Moon Landing

_____________________________

© 2019 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to [email protected]. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures

2 thoughts on “Apollo Astronauts Look Back During Gala at Long Island’s Cradle of Aviation Museum Marking 50th Anniversary of Lunar Landing”

Comments are closed.