by Karen Rubin and Martin D. Rubin

Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

Nantucket, a porkchop-shaped island just 14 by 3½-miles with just a few thousand inhabitants, hangs 30 miles out to sea off Massachusetts’ mainland. That creates a special kind of isolation and 350 years ago, made for a special incubator for culture and industry.

“Nantucket has been a microcosm of America for 350 years, a magnet and unique laboratory for some of our most powerful impulses…People around the globe knew of Nantucket whalers,” says the narrator of a documentary, “Nantucket” by Ric Burns. Nantucket, he says, has a history of reinventing itself.

“Nantucket was created by sea. In as little as 400 years, it will be taken by the sea. We are on borrowed time.”

That alone sets up the drama before our visit to Nantucket. The documentary is an evening’s activity aboard Blount Small Ship Adventures’ Grand Caribe, and now, we sail into Nantucket’s harbor in a dense fog, on the last day of our week-long voyage that has taken us to the New England islands.

This tiny place, we learn, became a global powerhouse because of whaling, which itself required technological innovations and produced a revolution in the way people lived: “Nantucket was the first global economic engine America would know.”

Indeed, here in Nantucket, we realize how revolutionary candlelight was, extending people’s days into the darkness of night. “Nantucket sperm oil made the Industrial Revolution happen.”

It also proves to be a lesson in the importance of globalization and immigration.

“In 1820, Nantucket entered its golden age. The entire Pacific its backyard, America as world power.” The square-rigged whaling ships we think of as quaint today “were state of art, decades into development, a perfect factory ship to render oil. They could go anywhere, withstand horrible conditions, serve as the home for dozens of men for three to four years at a time. They were vessels of exploration, the space ships of their day, they could travel to unknown worlds…Nantucketers were astronauts of their day.”

(I appreciate this all the more after having seen the “Spectacle of Motion: “The Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage ‘Round the World,” at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, a few days before on our own voyage. See story)

But here on Nantucket, we are introduced to another aspect of the story: Quakerism and feminism.

Whaling, it turns out, became a thriving industry because of the Quakers who settled Nantucket, peacefully coexisting with the Wampanoags who had lived here for thousands of years (their numbers were decimated, though, by the diseases the Europeans brought). The Wampanoags knew how to harpoon whales that were beached and introduced the English to whaling.

But it was the Quakers’ open-mindedness, their values of modest living, hard work and practice of reinvesting money into the industry rather than on lavish living that produced the innovations. Even more significantly, Nantucket could become so successful in whaling because of the Quaker sense of egalitarianism, seeing women as having equal ability. How else could Nantucket men go off for years at a time, leaving their home, business and community to be run by the women they left behind (one street is known as Petticoat Row because of all the women-owned businesses)? Quaker women, including Lucretia Coffin Mott (who was from Nantucket) became leaders of the Woman’s Suffrage Movement.

So it is no wonder that Nantucket enabled a woman, Maria Mitchell, to thrive.

Born in 1818 on Nantucket, Maria Mitchell became America’s first woman astronomer (famous for discovering a comet in 1847, which was named “Miss Mitchell’s Comet”), the first woman elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1848) and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1850). She was Vassar’s first professor of astronomy, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Women, and active in the Women’s Suffrage movement.

We first are introduced to her on “Gail’s Tours” of the island, then when we visit the Whaling Museum which has a whole gallery devoted to her, and after, I am so fascinated with her, I follow a self-guided “Walking in the Footsteps of Maria Mitchell” which takes me to the Quaker Meeting House. (Ironically, Mitchell was too skeptical and outspoken for the Quakers and “written out” so she joined the Unitarian Church instead, which today shares its building with the Congregation Shirat Ha Yam, “a pluralistic Jewish congregation”).

Nantucket has a land area of about 45 square miles (about half the size of Martha’s Vineyard), yet seems larger, somehow, to get around. The best way to experience Nantucket when you only have a day and when mobility may be somewhat limited, is to take an island tour.

So we take the launch boat into Straight Wharf (this is the only stop on the New England Islands cruise where we anchor instead of dock), and walk along the cobblestone streets about half-mile to where Gail Nickerson Johnson has her van parked in front of the Visitor Center.

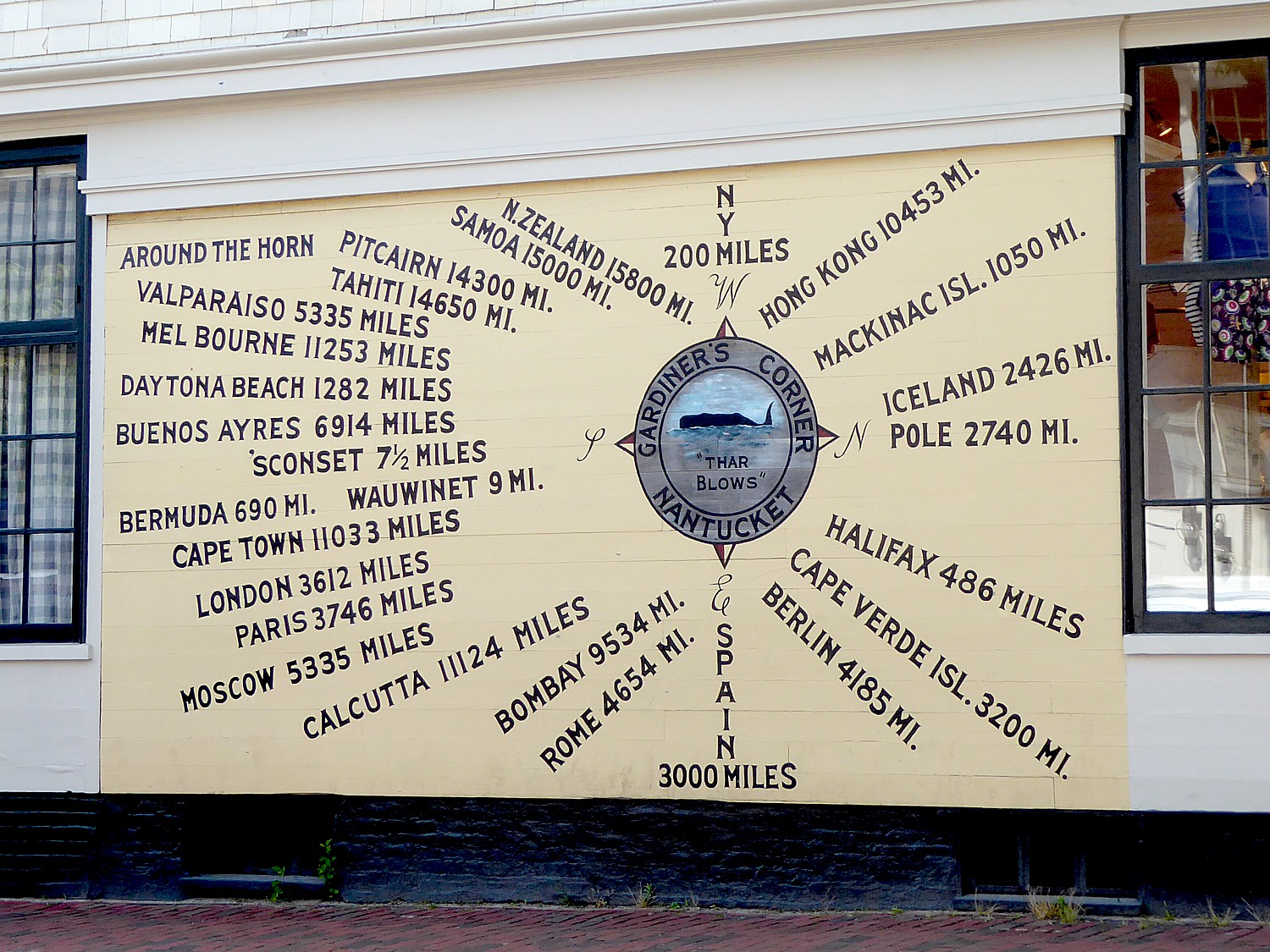

The first impression of Nantucket is how much it looks like a movie set with its quaint shops and cobblestone streets. Indeed, the one square-mile National Historic District is the largest concentration of antebellum structures in the United States. I take note of a mural on the side of a building that shows how many miles from places like Iceland, Pitcairn and Cape Town are from Nantucket, as if the center of the world.

We have been recommended to Gail’s Tours, and what a find this is. Gail, it turns out, is a 6th generation Nantucket native, descended from the Nickersons (her family line includes the Gardners, Coffins, Foulgers), was raised here, and knows just about everybody and every house we pass. She took over the tour business from her mother, who, she says, used to summer here before marrying her father. Her mother used to take visiting friends and relatives around in a woodie, and then got the idea to turn it into a tourist business, which she ran for 40 years.

Gail points out all the local sights:” I remember when….” “We used to ….,” “When we were kids….” “That used to be ….”

She notes that some 10,000 to 15,000 people live on Nantucket year-round, quite a jump from the 3,000 people who lived here year-round when she was growing up.

Gail jokes that Nantucket is on shaky ground – it is predicted to be under water in 400 years time. “In 300, I’m outta here.”

We pass all the important sights: the island’s oldest house, built as a wedding present for Jethro Coffin and Mary Gardner Coffin in 1686. It has been restored after lightening struck the house, splitting it in two; the Old Windmill (1746); the Quaker cemetery where there some 5,000 people are buried but few headstones, so it looks more like a rolling field; the Maria Mitchell Observatory; cranberry bogs; the Life Saving Museum.

She points to the house that Frank Bunker Gilbreth owned – the efficiency expert depicted in his son’s book, “Cheaper by the Dozen.” “They found among his papers Morse code for how to take bath in 1 ½ minutes.” The family still owns the house. She points to where Peter Benchley (“Jaws”) lived, the house where John Steinbeck stayed when he wrote “East of Eden.”

We stop at Sankaty Head Lighthouse so we can get out for a closer look. The 70-foot tall lighthouse was built of brick in 1850 and automated in 1965; its beacon can be seen 26 miles away. It had to be moved and was re-lighted in its new location, just next to the fifth hole of the Sankaty Head Golf Course in November 2007.

The tour finishes just around the corner from the Nantucket Whaling Museum. We pick up phenomenal sandwiches from Walter’s, have lunch on benches outside the museum.

Gail’s Tours, 508-257-6557.

Nantucket Whaling Museum

We had been to the excellent New Bedford Whaling Museum and now come to the renowned Nantucket Whaling Museum. Interestingly, the presentations and focus are very different – so the two are like bookends that add to the telling of this dramatic story.

We arrive as a historian is describing the hunt for whales, and then join the docent-led highlights tour, which is sensational.

The sperm whale oil, she says, “is a light source, power source and lubricant and could be used in winter. Artificial light in winter revolutionized life for 3 to 4 months of the year. It was used throughout the United States and Europe, prized the world over.”

The earliest whaling industry was created by Quakers, who were austere, not vain, and reinvested income into growing the industry. Portraits were not permitted (the portraits that decorate the entire wall are made later), but by the 19th century, they were not practicing Quakerism. She points to one of the earliest portraits which, without a tradition of art education in colonial America, was probably made by a housepainter, and probably an authentic representation of her likeness without artifice. She has one blue and one brown eye, which was a genetic trait among some of the earliest Nantucket settlers.

She points to a portrait of Susan Veeder, one of the women who accompanied their husbands on a whaling voyage. She kept records of the day-to-day life. “Her journals are anthropological, whereas the men’s journals were mainly about weather, tides and number of whales caught. She is the reason we know so much about life on whaling ship.” The docent adds that Veeder delivered a baby daughter while on board, but it died. “While British whalers had to have a surgeon on board, American whalers were not required to. The ship had a medical kit with numbered vials and instructions. But if they ran out of #11 vial, a captain might just add #5 and #6 together.”

Another painting shows a wife standing beside her husband seated at a desk. “It’s a rare image. Women had roles in Nantucket – they ran the town, home and business. Her husband was a whaling captain who brought back artifacts; she set up a display in house and charged admission fee and told stories. This was the first museum on the island. The contents went to the Atheneum and now are part of the Historical society collection.”

She points to a jaw bone that is the height of the room. It would have come from 80-ft whale such as rammed the Essex (the event that inspired the story of “Moby Dick”).”For people of Nantucket (most of whom had never seen a whale) would have been seen as a sea monster. For the captain to make the decision to keep this onboard for two years or so of the journey, taking up precious space on ship, speaks to how important it was.”

We go into the part of the museum that was originally a candle factory, built by the Mitchell family immediately following the Great Fire of 1846, where there is the only surviving spermaceti lever press left in the world.

She explains, “When the ship returned to Nantucket harbor, filled with as many as 2000 barrels of oil, each holding 31.5 gallons apiece, the oil would be put in storage.

“They would wait for winter to begin processing because only highest quality oil would remain liquid in winter; then process the lowest quality in spring and summer. They kept the lowest quality in Nantucket and sold first and second pressings.

“The best oil was used for lighthouses. What was left was used for spermaceti candles.These were the best candles – they burned with no odor, no smoke, no drip. They were prized throughout US and Europe. They changed the quality of life because of having a reliable light source.”

At its height, there were 36 candle factories in Nantucket.

You become aware of hearing sea chanties in the background.

She leads us up to the second-floor Scrimshaw gallery (those who have difficulty with steps can ask to use an elevator). “It was a way for captains to keep their sailors entertained and occupied (so they didn’t get into fights). They would soak whale teeth, burnish with shark skin (like sandpaper); sharks would be attracted to ship when processed whale – and they would kill sharks for food and use the skin.

“Sailors may be illiterate. They would trace designs from newspaper images and advertising. Victorian woman a common subject for scrimshaw because they were commonly used in fashion ads they traced.”

Some scrimshaw was functional – like pie crimpers. The men would fashion corset stays as tokens of love (they were worn close to heart). Only captains would have the space to make swifts – tools to wind skein of yarn.

Today, she says, the scrimshaw is priceless.

She notes that the Essex was not the only ship that was sunk by a whale: the Ann Alexander also was sunk by whale, but the sailors were rescued the next day and returned home.

“Another ship in the Pacific found a whale with a harpoon from the Ann Alexander in it – killed the whale and made scrimshaw out of its teeth, known as the Ann Alexander teeth” that we see here in the gallery.

There is a small room devoted to Essex story, and we come upon a storyteller retelling the story of the Essex, sunk by a whale – the event that inspired Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” – from the point of view of the actual events as documented in Nathaniel Philbrick’s book, “In the Heart of the Sea” which ended with the men so desperate, they committed cannibalism.

The cabin boy on the Essex who 30 years later wrote his memoir, was Thomas Nickerson (one of Gail’s ancestors? I wonder).

This was the first known incident of an unprovoked whale ramming a ship. But, he says, they now believe that it was hammering to quickly repair one of the chase boats used when they go after the whale, that caused the whale to charge.

Melville, it turns out, only visited Nantucket for the first time in 1852, after he wrote Moby Dick.

Most interesting is the room devoted to Maria Mitchell’s Legacy, where we are introduced to her biography and achievements.

The Nantucket Historical Association which operates the museum also operates several other attractions which are included on an “all access ticket”($20/adult, $18/senior/student, $5/youth 6-17): the Oldest House & Kitchen Garden (the 1686 Coffin House); the 1746 Old Mill (you go inside and meet the miller); the Old Gaol (1806), the Quaker Meeting House (1836), the Fire Hose Cart House (1886, the last remaining 19th century fire hose cart on the island); and Greater Light.

Nantucket Whaling Museum, 13 Broad Street, 508-228-1894, https://nha.org/visit/museums-and-tours/whaling-museum/ Allocate at least two hours here.

In Search of Maria Mitchell

Nantucket is dramatic, of course, because of the whaling industry – an invention that revolutionized life by bringing light into winter’s darkness and what the oil meant to enabling the Industrial Revolution.

But for me, the most fascinating thing is being introduced to Maria Mitchell – we are shown important sites associated with her on the island tour and at the museum. I am so inspired that I follow a self-guided walking tour that is delightful to give structure to exploring the town.

I meet her again in a storefront display dedicated to her, and then follow the Maria Mitchell Foundation sites: the Nantucket Atheneum (she became the first librarian, at age 18); the Pacific Bank where her father was president; the Unitarian Universalist Church which she joined after leaving the Quakers; Mitchell’s House where she was born, the Observatory built after her death in 1908 and the natural history museum operated by the Maria Mitchell Foundation (mariamitchell.org).

This leads me to the Quaker Meeting House where I have a most unexpected – and fascinating – discussion of Quaker religion sitting in a pew.

“Quakers were the social cement of the community.” You couldn’t do business without being Quaker, but you could pretend to be Quaker.

“Quakers were seen as activists, the hippies of their day,” because they were free thinking and were egalitarian in their treatment of women and people of other races.

The Quakers were considered heretics and banned by the Puritans because they believed in an “inner light”. They refused to pay taxes to the church or accept authority, or take oaths (for this reason, they couldn’t become doctors or lawyers). It went counter to the control mandated by the Puritans, Anglicans.

“They would show up naked at an Anglican Church,” she tells me which sparks a thought: why isn’t Quakerism being revived today? It seems more consistent with modern-day approaches to organized religion.

Most heretical of all: they did not require those they sought to convert to accept Jesus. “They did not require personal knowledge or acceptance of Jesus, just to find God through Inner Light.”

“The Quakers were hanged, branded, their noses split.”

But they found safe haven in Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard, because in 1661, Charles II ordered that all trials of Quakers had to take place in England. “They were safe in America since they wouldn’t be shipped back to England.”

And over time, the Quakers toned down the “dangerous” rhetoric.

“They were excellent businessmen. They valued education (to this day): boys were educated to 13 or 14 when they were expected to join the whaling ships; but girls were educated to 17 or 18, so they had more formalized education than men.”

The women, therefore, were left in charge of home, businesses and community when the men left for their whaling voyages. Centre Street was nicknamed Petticoat Row because women owned all the businesses.

On the other hand, Maria Mitchell must have stepped over the line, because in 1843, even though her father was an elder, her “skepticism and outspokenness resulted in her leaving Quaker Meeting and being ‘written out’ by the Society.”

The decline of Quakers in Nantucket followed the decline of the whaling business. A great fire in 1846 destroyed much of Nantucket’s infrastructure and the livelihoods of 8 out of 10 Nantucketers. When gold was found in California, in 1849, scores of whaling ships sailed for San Francisco and were sunk in the harbor there rather than return; when petroleum was discovered in Pennsylvania in 1859 as a cheaper, easier fuel, scores of Nantucketers went there. The ships, which had to be built bigger and bigger for the longer journeys, had trouble coming into Nantucket’s harbor because of a build-up of silt. Then the Civil War came – more than 300 Nantucket men joined the Union and 73 were killed; the whaling ships were easy targets for the Confederates. The last whaling ship sailed from Nantucket in 1869.

“By that point, Nantucket well out of picture,” the “Nantucket” documentary notes. “The city in the middle of the ocean was evacuated. It went from a population of 10,000 to 3000 in a matter of decades, like a sleeping beauty castle, waiting 100 years with only the memories of whaling.”

Now, the docent says, there is only one full-time Nantucket resident who is Quaker. “We get 5 to 8 people for Sunday meeting.” During that time, people sit and meditate; they do not even read a Bible.

I stop in at the Research Library where there is a stunning exhibition of needlepoint on display.

There is so much more to see; I make notes for my return visit:

Nantucket Lightship Basket Museum (49 Union Street, 508-228-1177, https://www.nantucketlightshipbasketmuseum.org )

Nantucket Shipwreck & Lifesaving Museum (158 Polpis Road, 508-228-2505, http://eganmaritime.org/shipwreck-lifesaving-museum/. The museum is located at some distance from the town; you can obtain a free Wave bus pass to the Museum at Visitor Services at 25 Federal Street in downtown Nantucket. Nantucket Regional Transit Authority is on 20 South Water Street not far from the Whaling Museum)

Cisco Brewers (5 Bartlett Farm Road, 508-325-5929, http://ciscobrewers.com/ . The brewery operates its own free shuttle, noon to 6:30 pm daily on the half-hour, from Visitor Services at 25 Federal Street downtown.)

Bartlett’s Farm (33 Bartlett’s Farm Road, 508-228-9403, https://bartlettsfarm.com/; located about 10-minute walk from Cisco Brewers.)

The ever-shifting sandbars lurking beneath the waters around Nantucket have caused between 700 and 800 shipwrecks, making lighthouses necessary navigational aids. Besides the Sankaty Head Lighthouse which we have seen there are two others that are worthwhile visiting:

Brant Point Lighthouse, standing at the entrance to Nantucket harbor, is the second oldest lighthouse in North America, first built in 1746 (the oldest is Boston Harbor Light c. 1716). Over the years, it has been moved and rebuilt more times than any other lighthouse in the country. The present lighthouse is the ninth one built on Brant Point. It is 26 feet tall wooden tower topped with a fifth-order Fresnel lens that was built in 1901. Still in active use, it is owned by the US Coast Guard and closed to the public, but you can visit the grounds (www.nps.gov/nr/travel/maritime).

Great Point Lighthouse (also called Nantucket Lighthouse), New England’s most powerful lighthouse, sits at the extreme northeast end of the island. A wooden tower was quickly built and the station with a light was activated in October 1784 (and destroyed by fire in 1816). The following year a stone tower was erected which stood until toppled in a storm in March 1984. The Lighthouse was rebuilt again in 1986, the stone tower was built to replicate the old one, and still remains in operation today. Modern additions include solar panels to recharge the light’s batteries, and a sheet pile foundation and 5-foot thick concrete mat to help withstand erosion.

Nantucket also offers miles upon miles of beach open to all. And thanks in large part to the early efforts of the Nantucket Conservation Foundation, nearly half of the island’s 30,000 acres are protected. A network of beautiful cycling paths wind through the island.

Contact the Nantucket Chamber of Commerce, Zero Main Street, Nantucket, MA 02554, 508-228-3643.

Now it is time to return to the Grand Caribe. (they make it very easy to step from the launch boat onto the stern of the ship through an open bay).

I’m back in time for the farewell cocktail reception, an open bar with delicious hors d’oeuvres. Dinner is lobster tail or prime rib (both fantastic); vanilla gelato or crème brule.

We are eating dinner when the fog starts rolling in most dramatically. Within minutes, it is difficult to see even the boats anchored nearby. The foghorn blasts every few minutes – which is funny as we sit in the lounge watching the movie, “Overboard,” when the blasts seem coordinated. (Jasmine, the cruise director, has opted for this romantic comedy instead of the movie “Perfect Storm.”)

It will be a nine-hour sail back to Warren, Rhode Island where the Blount Small Ship Adventures is based. Captain Patrick Moynihan tells us to anticipate three to four foot seats for about an hour when we reach Rhode Island waters.

Blount Small Ship Adventures, 461 Water Street, Warren, Rhode Island 02885, 800-556-7450 or 401-247-0955, info@blountsmallshipadventures.com, www.blountsmallshipadventures.com).

See also:

Endlessly Fascinating, Newport RI, Playground for the Rich, Makes its Attractions Accessible

Cruising into Martha’s Vineyard’s Warm Embrace

_____________________________

© 2018 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin , and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures