By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

The first thing you notice about the Thomas Cole House, “Where American Art Was Born,” is the view from his porch – out to the ridges of the Catskills Mountains, the Hudson River curving around a bend. It is not hard to imagine that in Cole’s day, there would have been fields between his house and the river. But it is the same scene immortalized in paintings renowned as the “first American art movement.”

Thomas Cole’s Cedar Grove, now the Thomas Cole Historic Site and Site #1 on the Hudson River School Art Trail, has been redone since I last visited – more of the house restored to the way it was when Cole, at 35 years old, married 24-year old Maria Bartow, the niece of the man who owned the house and farm where Cole was renting studio space for 10 years..

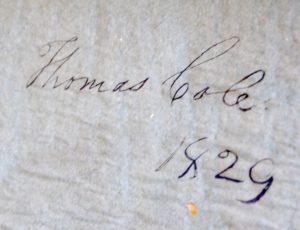

The guided tour has also been revamped with new innovative, multi-media features as well as personal effects – I love seeing Cole’s top hat, his musical instruments which he played and posed, his paint box, his traveling trunk with his signature and date, 1829 – and original paintings, and most especially his studio with his easel and paints and a room devoted to his creative process.

The presentation really personalizes the man, brings him into your presence. You start the guided tour in the parlor that Thompson, who really encouraged Cole, turned into a sales office for the artist. What appears to be Cole’s portrait – a video projection – becomes a slide show of his art as a voice narrates from Cole’s own journal and writings. Around the room are projections or digital reproductions of Cole’s paintings (some of Cole’s original paintings are in upstairs rooms we visit). He describes the inspiration and rejuvenation he feels from this wilderness, how he is “deliriously happy” at having his family, and his outrage over the “ravages of the axe” of progress.

These themes come together in his work: while primarily a painter of landscapes, he expressed his philosophical opinions in allegorical works, the most famous of which are the five-part series, The Course of Empire, which depict the same landscape over generations—from a near state of nature (depicting American Indians) to consummation of empire (Rome), and then decline and desolation, which is now in the collection of the New York Historical Society (and will be on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2018); and four-part The Voyage of Life, which are reproduced in his studio. (“Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings” will be on view at the Met, January 30-May 13, 2018, and feature some of his most iconic works, including The Oxbow (1836) and his five-part series The Course of Empire (1834–36, www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/thomas-cole,).

I appreciate Cole as very possibly America’s first environmentalist, the first to appreciate conservation and raise the alarm over the march of progress at a time when the Industrial Revolution was taking hold and technological progress was worshipped along with capitalism, as he railed against the “copper-hearted barbarians” and “dollar-godded utilitarians.”

“We are still in Eden; the wall that shuts us out of the garden is our own ignorance and folly,” he says, as a projection of his painting, “Expulsion from the Garden of Eden” (1828) appears.

Cole worried that America’s rapid expansion and industrial development would destroy the glorious landscape – in 1836, he could see the railroad being built through the valley and he bemoaned the loss of forest along Catskill Creek, “the beauty of environment shorn away.”

Cole recognized America as a land in transition – the settled and domesticated juxtaposed with the wild and undomesticated… He witnessed the changes taking place around him.. And in the early 1800s, America was still in process of creating own culture, distinct from the European settlers.

An Immigrant Dazzled by America’s Wilderness

Thomas Cole was born in Lancashire, England, in 1801 and emigrated to the United States with his parents and sister (his father was in textiles) in 1818, settling first in Philadelphia, then Steubenville Ohio, then New York City. He had little formal art training; he picked up the basics from a wandering portrait painter. Cole soon focused on landscape and ultimately, Cole transformed the way America thought about nature and the way nature was portrayed on canvas.

As an immigrant, Cole was dazzled by America’s vast stretch of untamed wilderness, unlike anything that existed in Europe. At this point in time, though, most Americans did not appreciate the wilderness – they thought of it as something to be feared or exploited. Instead, America was enthralled with industrialization, technology and progress.

Cole was 24 years old when he took one of the new steamships up the Hudson River (it was “the thing to do” at the time). He made a painting which sold immediately, came again to make another painting and that sold immediately, as well. He came so often he looked around for a studio in the village of Catskill. He came to Cedar Grove, John Alexander Thompson’s 110-acre farm with an orchard and a hilltop view out to the Hudson River and the Catskill Mountains – the same view we see today – and for the next 10 years, rented a studio in a structure next door to Thompson’s house (where Temple Israel now stands).

Cole fell in love with Maria Bartow, Thompson’s niece 11 years younger than Cole, then 35 years old, and moved into Cedar Grove permanently, all living together in the modest house which Thompson had built in 1815.

Thompson provided Cole with the two parlors on the main floor to use as “sales rooms” for his painting, and built a studio for Cole, cutting out a window so he would have northern light.

Thompson also built a studio for him with a high window to bring in northern light, and we see his paints and easel as if he had just left the room for a moment.

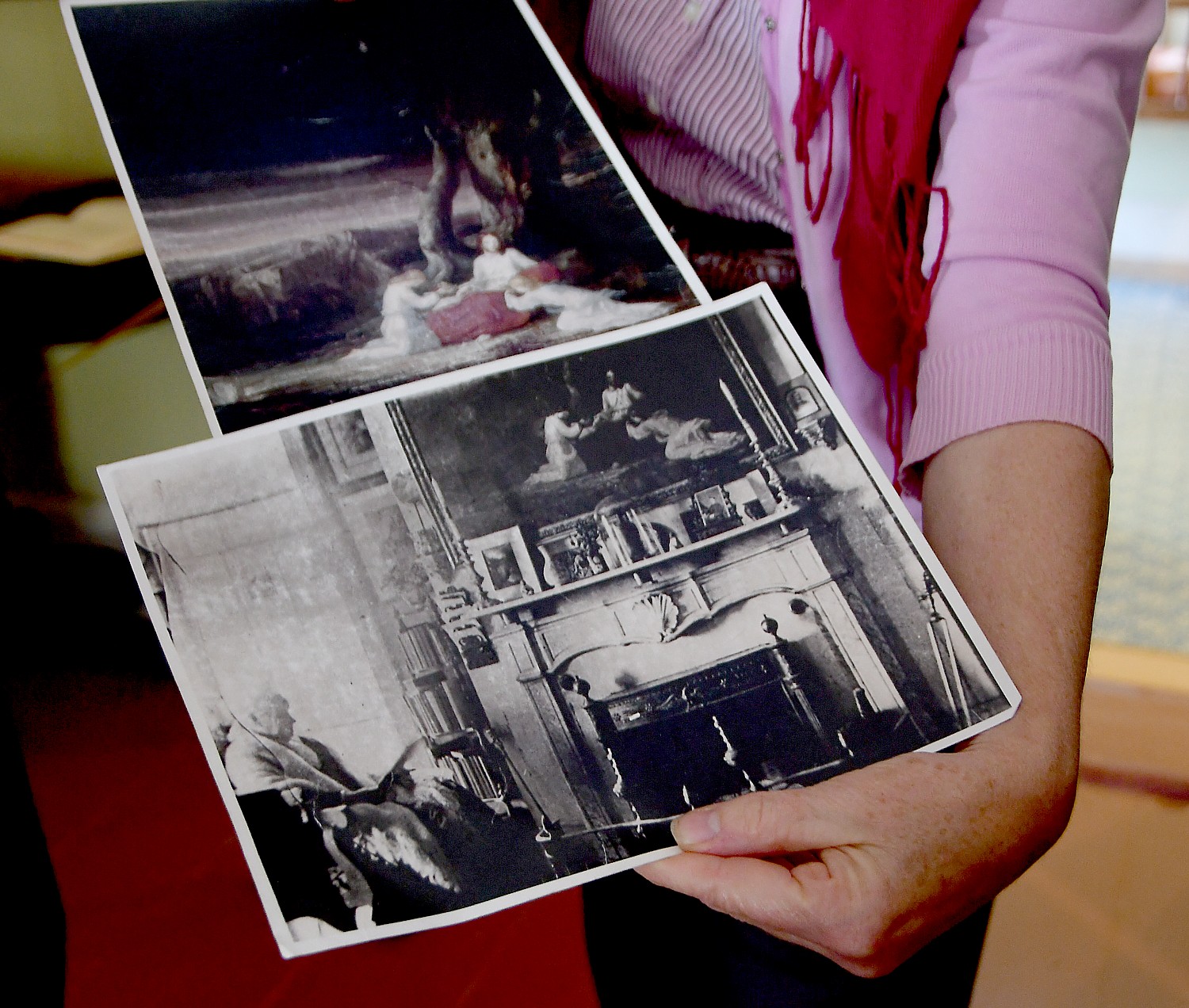

Cole’s studio, which Mary’s uncle made for him, installing a high window to bring in northern light, has been restored. It is where he painted one of his most famous series, the four “Voyage of Life” paintings (he painted eight sets of four; one of the sets is in the New-York Historical Society and will be on display January 2018 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art). We see his paints and easel as if he had just left the room for a moment.

Alas, the studio probably contributed to his early death, at the age of 47, when his wife was pregnant with their fifth child – the studio in winter had little ventilation and he was working with turpentine and paints and had a respiratory illness. He died of pleurisy. Mary named their son Thomas Cole, Jr.

Frederick Edwin Church, recognized as a prodigy, was 18 years old when Cole, then 43, took him on as an art student. Cole would take his six-year old son Theodore out with them painting. Paintings by Church that have a small boy are likely Cole’s son. After Cole died, in 1848, Church, who built his Olana on a hilltop on the opposite shore of the Hudson, helped the family, even hiring Cole’s son Theodore as his farm manager.

Cole’s Creative Process

Touring the house is remarkable because it contains many of Cole’s personal effects including several of his paintings, like “Prometheus,” and his special items like musical instruments that he played and used as props for his paintings.

All of this is fairly miraculous because the house was sold in the 1960s and the contents auctioned off – the paintings, the furnishings. Over the years, many of the sold items have since come back, like “Uncle Sandy’s” chair, which we see today, which was purchased by a local postman who donated it back to Cedar Grove.

In a living room on the second floor, Cole’s letters “appear” on his actual writing desk (triggered by a motion detector); some of the paintings that decorate the room where they would have been are reproductions (the originals held in museums), but some are originals. There are black-and-white photos of his daughter in her later years, sitting in that very room. I am fascinated to see his “magic lantern” (an early slide projector with hand-painted glass slides) that drew its light from a candle inside. We appreciate Cole as a man of enormous talents –a poet, essayist and musician in addition to an artist and we see some of his instruments. We visit his bedroom and see his traveling trunk which he had made on Pearl Street, with his signature and date.

We learn that he was close friends with the novelist James Fenimore Cooper and provided illustrations for his work, including “The Last of the Mohicans” (1827) and “The Pioneers.”

My favorite room is his “Process Room” where we see his actual sketches, his paint box which he decorated with a beautiful painting and papers and his famous color wheel.

On my hikes on the Hudson River School Art Trail, I wondered how Cole would have captured the scenes – the sheer logistics of getting to these remote places that take us 20 minutes to reach by car along paved roads. Cole painted at a time before photography was a handy tool, before capped paint tubes made painting “en plein air” as feasible as it was for the Impressionists decades later.

I learn that Cole hiked with a pocket easel and pencil. He would get to a place like Sunset Rock by dark (a trail which I hike), camp and stay there a few days. He made copious notes of the smallest details – the light, color (he created a color-wheel for himself which we see), the atmosphere, the vegetation and natural forms.

But then he would wait before he painted the scene, for time to pass “to put a veil over inessential detail to turn it into beautiful and sublime…He had a vision of nature as an expression of the divine.”

It is important to realize that at the time, a painting afforded the only way for people to see places without actually visiting for themselves.

He began to turn his landscapes into allegorical exposition. Over a three-year period, he painted “The Course of Empire” a series depicting the same landscape over centuries and generations as civilization rises and falls, from savage to civilized, from glory to fall and extinction. He intended the series as a warning against American unbridled expansion and materialism. It took him three years to create and earned him a veritable fortune in commissions and fame.

Cole also became progressively more spiritual – coinciding with a rise in spiritualism in America. – and used his landscape painting as religious allegory. This is manifest in Cole’s “Voyage of Life,” a series of four paintings that show a pilgrim from infancy to old age, led by a guardian angel, which became Cole’s most popular work.

Each year, there are always special exhibits as well – in the Cole house, oddly juxtaposed with Cole’s 18th century works (we even see the wall trim that he painted himself) is a contemporary artist, Kiki Smith. In the New Studio, a separate building, this season is “Sanford R. Gifford in the Catskills.”

Most days when you visit the Cole house, you take a guided tour, but on Saturday and Sundays, 2-5, you can tour the house on your own. The house usually closes at the end of October but this year, it is open for three weekends in November.

Thomas Cole National Historic Site, 218 Spring Street, Catskill, NY 12414, 518-943-7465, www.thomasscole.org (Normally open May-October, but will have extended season this year, three weekends in November).

Get maps, directions and photographs of all the sites on the Hudson River School Art Trail at www.hudsonriverschool.org.

A great place to stay: The Fairlawn Inn, a historic bed-and-breakfast, 7872 Main Street (Hwy 23A), Hunter, NY 12442, 518-263-5025, www.fairlawninn.com.

Further help planning a visit, from lodging to attractions to itineraries, is available from Greene County Tourism, 700 Rte 23B, Leeds, NY 12451, 800-355-CATS, 518-943-3223, www.greatnortherncatskills.com and its fall hub http://www.greatnortherncatskills.com/catskills-fall-foliage

See also:

_______________________

© 2017 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin , and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to [email protected]. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures

2 thoughts on “Fall Getaway in the Catskills: Thomas Cole National Historic Site is Site #1 on the Hudson River School Art Trail”

Comments are closed.