By Karen Rubin, with Eric Leiberman and Sarah Falter

Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

This is the day that many of us have had on a bucket list, and for some of us, represents the fulfillment of a “trip of a lifetime”: Machu Picchu.

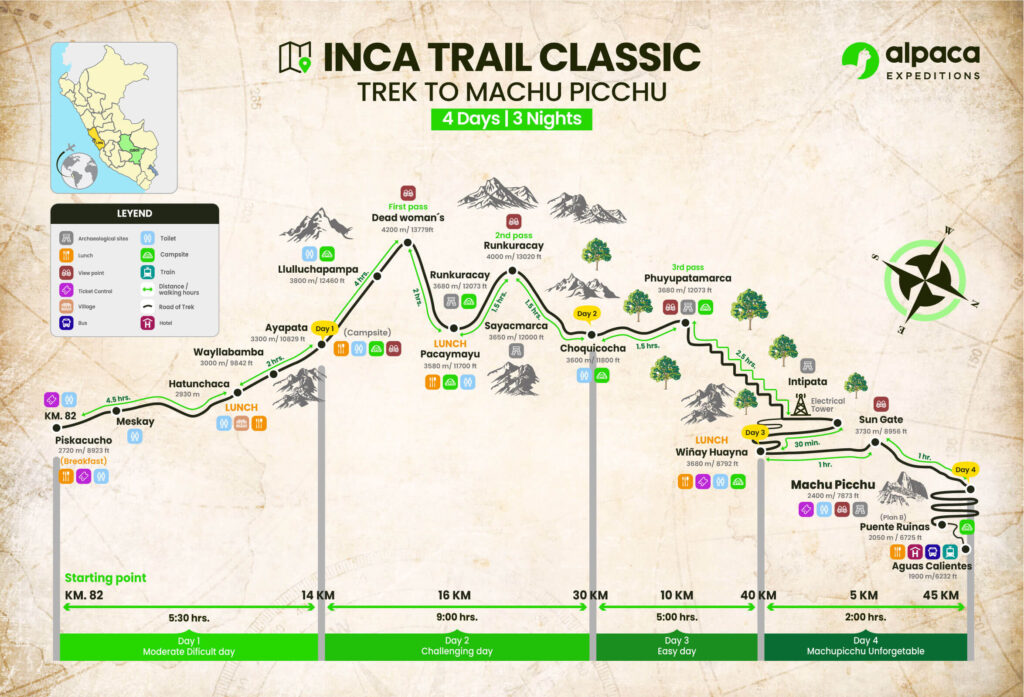

We are awakened at 3 am when the Alpaca Expeditions staff bring hot coffee to our tents. We have everything ready for leaving the Wiñaywayna campsite by 3:15 am (I had packed everything the night before and only kept out what I would be taking on the trail), and set out, our bagged breakfast in hand, wearing our headlamps in the dark for the surprisingly short distance walk to the check-in point for Machu Picchu where we wait until it opens at 5:30 am.

Our guide Lizandro Aranzabal Huaman wants us to get up so early to be first on line (he claims to have a 98% success rate) and also to get to the Sun Gate as the sun rises (and before it gets overwhelmed with photo-snappers), and to Machu Picchu in time for the first rays to illuminate the scene. In fact, there is only a group of six ahead of us and something like 200 behind us, checking our passport against the list of permits granted for the day.

Somehow, I wind up leading our pack of 15 trekkers and I surprise myself at the pace I set for the one-hour hike on this mostly flat portion of the trail to the Sun Gate. I am in the lead until we get to what Lizandro calls the “Gringo killer”- 50 of the steepest steps – more like a rock climbing wall – where you need to use your hands to crawl up like cat.

Lizandro has prepared us for the fact that the sun only comes through the Sun Gate (Inti Punku) at sunrise on the solstice. But from here, we get our first view of Machu Picchu in the distance (it’s still an hour’s hike away).

One of the many nice aspects of our guides, Lizandro and Georgio, is that they have been patiently taking individual and group photos of us with our phones and cameras at each of the key spots along the trail, and so we stop at the Sun Gate to take our turn posing for those shots. (Everyone wants to be at this small point for the sunrise, which is why Lizandro wanted us first.)

And then we continue (downhill!) from the Sun Gate at 8,956 ft. elevation, an hour more to Machu Picchu, descending to 7,873 elevation over the course of three miles from the Wiñaywayna campsite. At the same time, the temperature which had been cold at the highest elevations, becomes warm, even balmy, so we are actually sweating (need sunscreen and hat!) at the site.

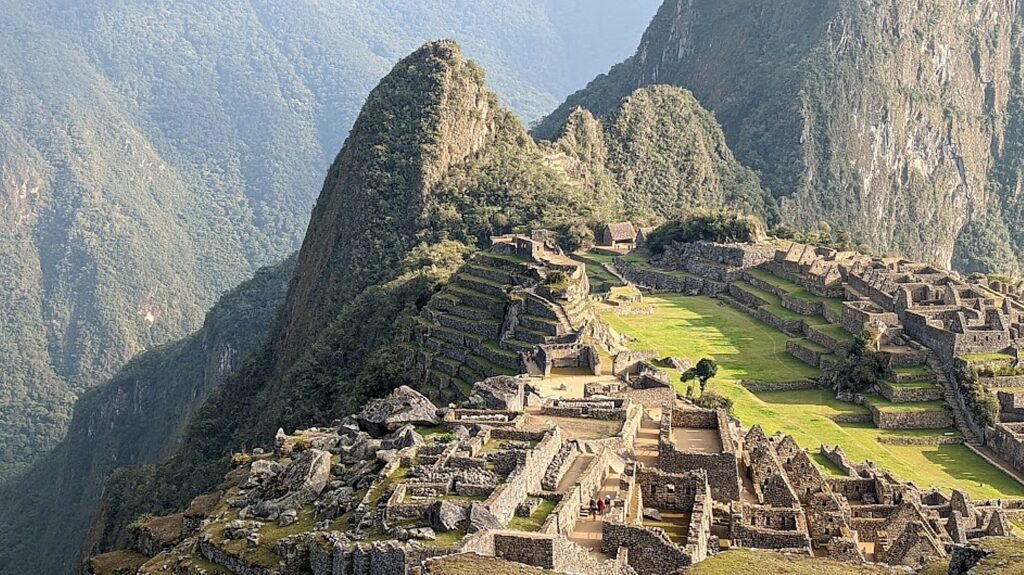

This part of the Inca trail gives us views that show how Machu Picchu is positioned – we see the entirety of the Lost City (I can only imagine what it was like before it was excavated) and how it is etched amid the contours of the mountain peaks – which is how it was kept hidden from the Spanish when they invaded in 1538 and for 400 years.

Literally 10 seconds after I pass a scenic overlook, the sun pokes out. (These views and so much more, are why we take the Inca Trail trek.)

At about 7:40 am, we walk in what seems to be a back entrance into the city, where we are perched on high terraces and the views are the iconic ones of magazines and postcards (and I suspect are not available to the day-trippers who come in from the bottom entrance for the tour). How lucky we are because the sun breaks through, highlighting the structures, for exquisite scenes.

We actually walk down and out of Machu Picchu site to wait for our ticketed time to re-enter (you can only stay 2 ½ hours and can only come in with a guide). While we wait, we have to use the bathroom before we reenter and check bigger backpacks and hiking poles.

Our scheduled time to enter Machu Picchu to begin our 2 hour private guided tour with Lizandro is 8:30 am, who leads us on Circuit #4 (there are four different circuits to control crowds) to the highlights: the terraces, Sun Temple, Royal Mausoleum, Palace, Plaza, Sacred Rock.

Machu means “old,” “ancient,” “big”). Picchu means “peak,” so Machu Picchu actually means “Ancient Mountain,” but that is not its indigenous name.

Lizandro tells us that Machu Picchu was built in the mid-1400s by Pachacuti, the 9th Inca king but its first emperor and the “Alexander the Great” , the Empire Builder, of the Inca. Beginning in 1438, he and his son Tupac Yupanqui began a far-reaching expansion that brought much of the modern-day territory of Peru under the ruling Inca family control. He rebuilt Cuzco, built Pisac, Ollantaytambo as well as Machu Picchu. He built Machu Picchu up in the mountains instead of the valley to be closer to the sun, to connect the sky and the earth in one place, as well as for protection. “Mountains were gods that protected the villages and the animals,” he relates. Almost all of the construction faces east to catch the sunrise – the Inca rulers claimed to be the children of Inti, the Sun God.

Over the next 100 years, the Empire ultimately expanded to what are today six South American countries, connected by 25,000 miles of roads, suspension bridges and trails, and controlling a population as many as 18 million.

The Sun Gate was built as a check point to enter Machu Picchu, but positioned so that on December 22, the summer solstice, the sun beam would come through gate; and on June 21, it comes through the other window.

Machu Picchu is built in two sections – an urban sector has some 200 units of which 172 were homes, and the rest were temples, and a sun dial.

There would have been 700-800 people living here full time – 60% were nobles, the rest were farmers and workers.

How did they build Machu Picchu without slaves, without animals to carry, without a wheel, iron tools, or written language? Consider that China’s Great Wall and the Egyptian pyramids were built with slave labor, draft animals, a wheel, iron tools and written language.

What they had was a culture and a labor system based on principles: Ani – reciprocity – one for all, all for one; Minka – community benefit – care for vulnerable – collectivity (how the Peruvians got through Covid despite a poor health care system); and Mita – paying taxes by work, labor (not cash) to benefit the whole.

It took 50-60 years to build Machu Picchu for Emperor Pachacuti, who ruled from 1432-1472, but it was never finished. I can’t help but wonder how many men were impressed to build this enormous complex of structures in that amount of time.

When the Spanish invaded in 1538, Machu Picchu was abandoned before it was finished and the Incan forces fell back to arm Vilcabamba, the Inca’s last stronghold. “They promised to come back but didn’t,” Lizandro says.

It is mindboggling to contemplate that as complex a construction as what we see, the scale, and the fact that more than 60% is still unexcavated, buried under 400 years of overgrowth.

The archaeologist Hiram Bingham didn’t discover Machu Picchu (it was discovered in 1902 by Bolivian fortune hunters looking for Incan treasure), but came on an expedition in 1911 in search of Vilcabamba, the last stronghold of the Inca after the Spanish conquest.

“He set up tents at base, met a local to ask where Vilcabamba might be. The man didn’t know, but on July 24 1911, with machete in hand, Bingham had a big surprise: the sight of Machu Picchu took his breath away. Two families were living here, cultivating the terraces two years before Bingham arrived. They were running away from paying taxes to the government.” [Off the grid?]

Bingham returned for a second, then a third expedition. He uncovered eight Inca trails (the Inca destroyed many of the trails to prevent the Spanish from reaching Machu Picchu) and took away artifacts, he claimed, for two years. “More than 100 years later, Yale still has the artifacts and is requiring Peru to build a museum to hold artifacts near Machu Picchu. But Peru wants it by the river. In 2015, the United States sent 11 percent of the artifacts back – but not all were real, some were replicas that they returned. The Peru government wants all of it back.”

The photos Bingham published brought international attention to Machu Picchu, the “Lost City of the Inca” – and tourists. The first tourist following the Inca trail came in 1954 and this Incan Citadel has become the most visited tourist attraction in Peru. The site was named among the New Seven Wonders of the World and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983.

We trekkers follow Circuit 4 (there are four circuits, to spread out the crowds): starting at the Main Gate (where we must present our passports and permit), to the Sun Temple, House of the Inka, the water foundation; Granitic Chaos; Sacred Plaza; Intiwatana Pyramid; Sacred Rock; Three Gates; Water Mirrors; and Condor Temple.

We climb the steep stone steps and come to the Sun Temple. It was built as a royal tomb to contain the mummified remains of the king. Lizandro points to how a temple would have the highest quality building stones and most precise placement and its architecture emphasizes the “harmony between people and nature. They always incorporate the natural bedrock. The windows are aligned for summer and winter solstice – a solar observatory. There are three steps – the Inca triology. The mummified body was placed in the tomb in fetal position.” There are no mummies left in the tomb, but there would have been mummies of the 12 Inca kings (others were buried). On the day of Ayamaki, the mummies would have been paraded from the mausoleum.

Lizandro notes that the word ‘jerky” – the dehydrated meat snack – comes from the indigenous Quechua word, “jakky charky” (related to mummification).

We come to the Royal Inca Palace, where we can see that instead of windows (too cold), there would have been shelves for idols. “Bingham got here in time to see some.”

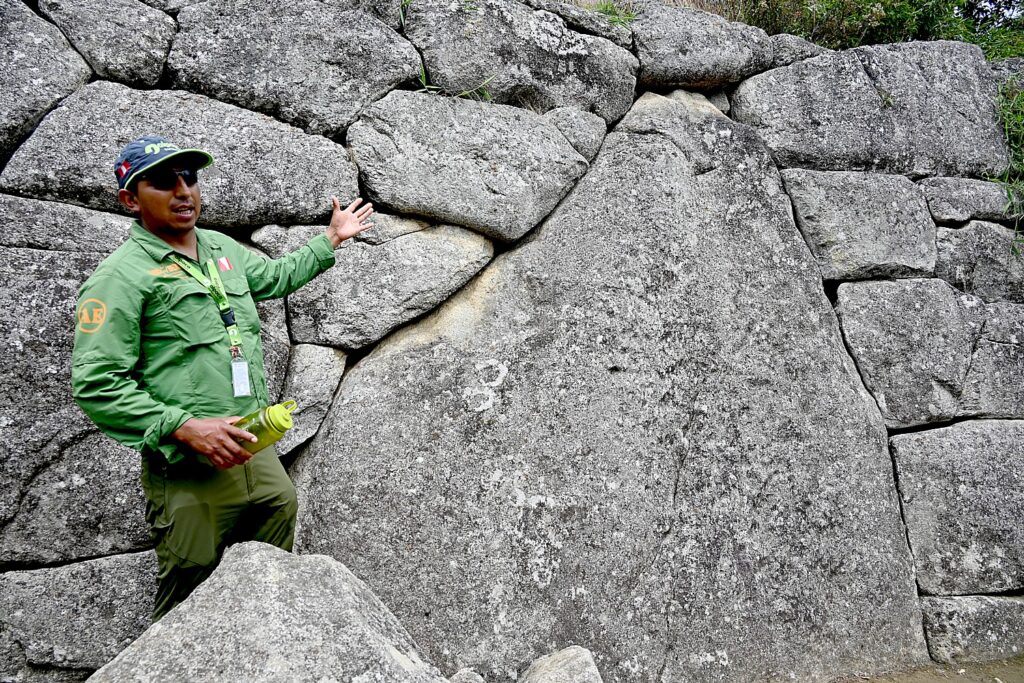

How would they have set the weighty keystone in place? With ramps, aloe vera to make it slick, he says. The enormous stone building blocks, weighing tons, are trapezoid shape and set at a slight incline angle, for stability against earthquakes. Indeed, Peru suffered two big earthquakes – in 1650 and 1950 – when the colonial buildings collapsed, the great cathedral in Cuzco collapsed, but these structures remained (in fact, the 1950 earthquake in Cuzco unearthed Incan structures). We see under one massive block a roller-shaped stone – a precursor to the wheel.

You only appreciate the scale of Machu Picchu as you haul yourself up the high steep stone steps. The straight lines and perfect angles, the precision, the sheer size and bulk of the stones, and how this entire city is nestled on a plateau amid these sheer mountain peaks.

There is a large open area, like a field, which would have been used for festivals, activities, an amphitheater. And in the middle, is what would have been a sundial. In 1978, the then president invited the Spanish King and Queen to visit, and their helicopter landing in the field, broke the sundial. (I find it ironic that the Spanish were still destroying Incan heritage.)

In this small plaza, Lizandro points out a huge section of bedrock cut to mimic the shape of the mountain behind – mountains were considered sacred.

He explains a bit of the Incan society hierarchy – the Inca were the royal family and nobles – perhaps 20,000 who ruled over a population of dozens of different tribes totaling as many as 18 million across much of South America. Professionals could become nobles (rise to that privileged class) because of their expertise, skill and function. Teenagers could show a talent and go into a profession.

We sit around for a bit of a rest, and Lizandro explains some of the contemporary politics. Apparently, in the 1990s, President Alberto Fujimori [a fixture in Peru’s politics from 1990 to 2003] wanted to privatize Machu Picchu – selling it off to Chilean investors, drawing an outcry of protests from the people. “The president did well his first five years – investing in industrial farming – but after he was reelected, he sold off or privatized without people knowing.” Fujimori, the son of Japanese immigrants, wound up being investigated for corruption. He tried to flee to Japan and was captured enroute in Santiago with eight suitcases of cash. He was convicted and sentenced to 17 years in prison.”

Lizandro says the Peruvian constitution (which I subsequently read has been rewritten and set aside multiple times since the country’s independence, while the government has undergone a series of coups back and forth from dictatorship to democracy, socialism to capitalism) favors foreign companies (they don’t pay tax). Because 50 percent of Peru’s population lives in Lima, he tells us, the people who live in rural areas, in the mountains, have little say.

Several of our group have obtained permits in advance to climb Huayna Picchu – that famous nub of a mountain, like an overlord, in the iconic Machu Picchu images – and Sarah has obtained one, while the rest of us continue touring Machu Picchu with Lizandro.

Sarah reports back that the 45-minute hike is extremely arduous – much harder than the Inca Trail hike – almost straight up to a tiny perch at the top, at 8,835 ft., 850 ft. higher than Machu Picchu, where everyone has to take turns for the photo, but you get a famous view of Machu Picchu. The trail was built by the Inca who also built temples and terraces at the top. “I would definitely recommend it to fitter hikers looking for one last challenge. It’s not super long and being able to see the scale of Machu Picchu from above was really impressive.”

We finally come back down to the entrance/exit to Machu Picchu and Lizandro hands us a ticket for the bus that takes us down an extremely winding road to the village of Aguas Calientes. We meet for a last lunch together in a local restaurant – kind of a celebratory meal ( optional and not included). Lizandro gives us our train ticket, departing Aguas Calientes 3:20 pm (you need to take seriously the notice to be on the platform at least 30 minutes ahead of time, which is when the train loads) to Ollantaytambo.

The train is wonderfully vintage, with roof-windows, and very comfortable for the two-hour trip (which for some reason takes us much longer). At Ollantaytambo, we are met by the Alpaca Expeditions bus for the two-hour drive back to Cuzco and drop off back at our hotel.

Candidly, I had been so obsessed about getting passed Day 2, Machu Picchu was more of an end-goal of a quest than the prime attraction – being here means I had gotten over the Dead Woman’s Pass, completed the 26 miles, going as high as nearly 14,000 feet – much as it would have been for the pilgrims who undertook this journey of a lifetime. It is personal.

For me, it is not just a trip of a lifetime but a now or never proposition.

I am not the only one celebrating an important milestone. Indeed, this is the sort of bucket-list trip that warrants a milestone – Peter timed reaching Machu Picchu for his 35th birthday; a couple had just gotten engaged at the start of the hike; another 30-something couple (he’s Italian, she’s Dutch) is on their honeymoon .That’s how special this trek is, embodying physical, spiritual – just as it did for the Inca, a triumph of will and willpower. A test of character then as now.

You are at the same time amazed by the ability of these people to construct these sites at all, but then wonder at the level of control exerted, the role of religion in maintaining that control and how authoritarians throughout human history use religion (the divine right). No surprise: the Inca kings claimed to be the son of the Sun God, Inti. And yet, you can’t help but marvel at the accomplishment of that government capable of building the 25,000 miles of roads, in producing the amount of food to sustain the population, and unifying a population of 18 million into a society.

You appreciate the social structure that produced these extraordinary mountain villages in a society that did not have slaves nor currency, did not have the wheel or beasts of burden, did not have compass, ruler, alphabet or written language.

Most astonishing, these structures were built within 20, 40 or 60 years’ time – apparently, each chief would select a project to be completed within his own lifetime.

Photos do not do justice, you have to stand next to the rock walls, trace how the boulders link to perfectly together, see the curve at the edge, the inclined angle (for stability against earthquake) with such exquisite precision, hoist yourself up the steep stone steps, look beyond to the distance these boulders would have had to be transported from their quarry.

You stand perched on these terraced structures built into the side of a mountain and simply cannot fathom what it took to build.

All these thoughts come to me as I step, climb, step, climb the trail.

At each site, Lizandro tells us more of the story of the Inca and the society they created – but unlike the sturdy bedrock that these sites were built on, the Inca’s hold on the people was really not that strong because it was not a bond. At a certain point, their hold was by force. “The Inca weren’t very nice people,” he says softly.

What was unexpected was to come away with an understanding of the limits of authoritarian control. Indeed, the Inca ruled for less than 400 years, but the empire existed only for a century before it was toppled, too weak and lacking support of the people, to withstand the Spanish invaders. There are lessons for day. And as we learn, Peru is still going through these cycles of economic struggle, political ping-pong between dictatorship and democracy, socialism and capitalism, since becoming independent from Spain in 1821. The more things change, the more they stay the same, may well be the lasting lesson.

What makes a “trip of a lifetime” – one that is truly life-enhancing, even life-changing? It is the doing.

Alpaca Expeditions offers many ways to get to experience Machu Picchu – the trek is its own experience, and when you think about it, is very inexpensive (from $650); it’s not even that difficult or expensive an airfare to reach (at this stage, you fly through Lima or Quito to Cuzco, but a new international airport is being built closer to Cuzco). The tour company also offers many different programs – like the Sacred Valley excursions – to different areas.

The permits to do the Inca Trail trek are limited to 500 a day for all the trekking companies (which includes 200 for trekkers and 300 for porters and staff) and get booked up months in advance.

More information: Alpaca Expeditions, USA Phone: (202)-550-8534, info@alpacaexpeditions.com, raulmanager@alpacaexpeditions.com, https://www.alpacaexpeditions.com/

See also:

VISIT TO PERU’S SACRED VALLEY IS BEST WAY TO PREPARE FOR INCA TRAIL TREK TO MACHU PICCHU

INCAN SITES OF PISAC, OLLANTAYTAMBO IN PERU’S SACRED VALLEY ARE PREVIEW TO MACHU PICCHU

ALPACA EXPEDITIONS’ INCA TRAIL TREK TO MACHU PICCHU IS PERSONAL TEST OF MIND OVER MATTER

DAY 1 ON THE INCA TRAIL TO MACHU PICCHU: A TEST

DAY 2 ON THE INCA TRAIL TO MACHU PICCHU: DUAL CHALLENGES OF DEAD WOMAN´S PASS,

RUNCURACCAY

DAY 3 ON THE INCA TRAIL TO MACHU PICCHU: TOWN IN THE CLOUDS, TERRACES OF THE SUN

& FOREVER YOUNG

DAY 4 ON THE INCA TRAIL: SUN GATE TO MACHU PICCHU, THE LOST CITY OF THE INCAS

__________________

© 2022 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures