Edited by Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

From coast to coast, Canada’s heritage, culture, wilderness beckon ecotourists this summer.

Experience Indigenous Cultures in British Columbia

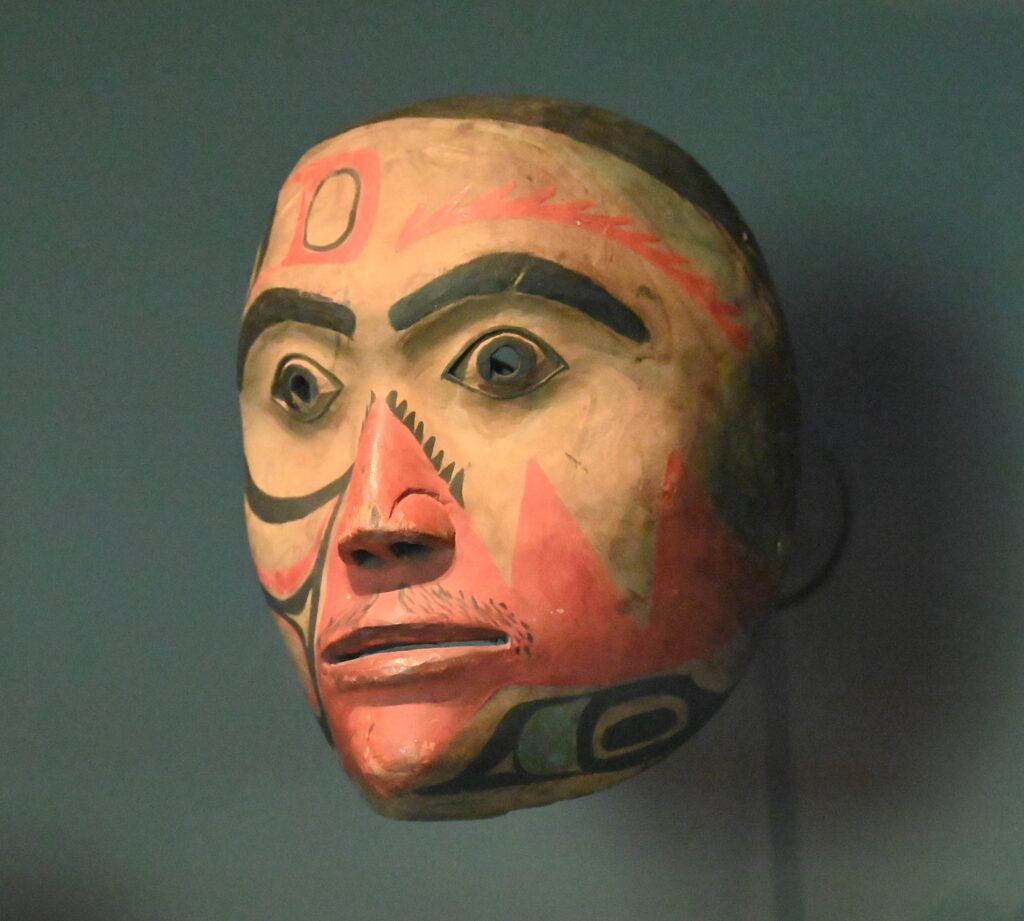

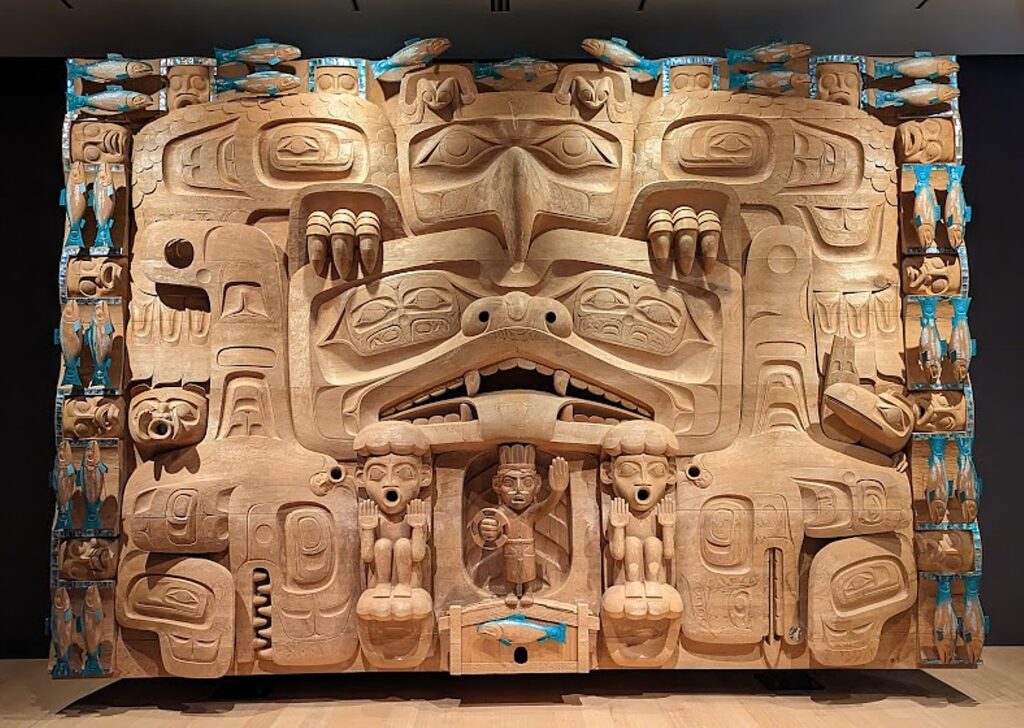

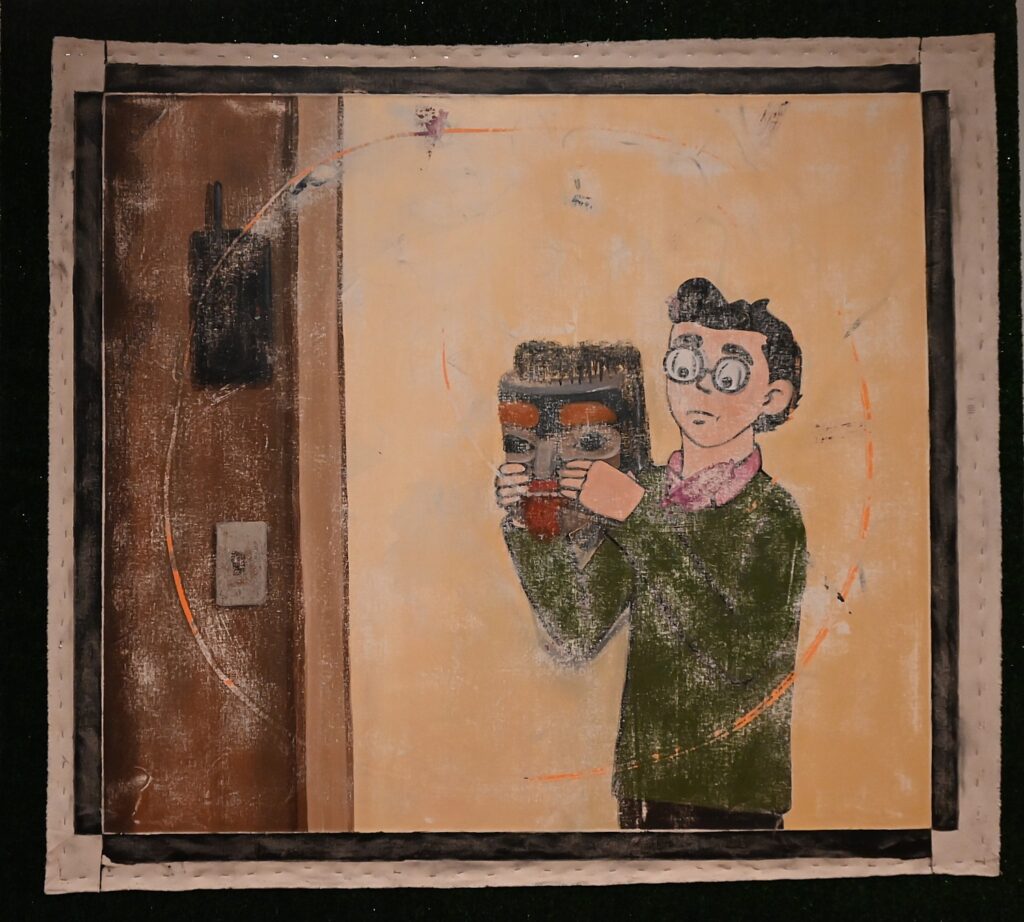

June is National Indigenous History Month in Canada, culminating in National Indigenous Peoples Day on June 21, but all summer long, British Columbia offers any number of ways to experience histories, traditions and values of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples. Indigenous tourism encourages visitors to understand and respect different perspectives of the world, and to experience histories, traditions, and values in an authentic and unfiltered way.

British Columbia has the greatest diversity of Indigenous cultures in Canada: of the 12 unique Indigenous language families in the country, seven are located exclusively in BC. Together, there are 204 unique Indigenous communities in BC. Here are 11 ways to engage in Indigenous experiences in British Columbia this summer.

A Three-Hour Song, Dance & Cultural Experience – During festivals, weddings, and potlatches, the Tla-o-qui-aht People come together to share a wholesome meal while exchanging wisdom and stories, with the belief that good food facilitates an easier reception to teachings. Visitors can join the tradition at the Best Western Plus Tin Wis Resort in Tofino, where the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation will host naaʔuu (which means “feast” in the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation language), an immersive experience taking place on select dates in June. The three-hour experience tells stories from the Nation’s history through song, dance, and traditional carvings, presented during a symphony of cultural delicacies and foraged ingredients. Proceeds go back to the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation to support language and cultural resurgence. Tickets start at $199 per person and can be purchased here. (Get there: From Vancouver, fly into Tofino-Long Beach Airport with Pacific Coastal Airlines, or right into Tofino Harbour with Harbour Air. Alternatively, you can take a ferry from Vancouver to Nanaimo or Comox and drive approximately 3.5 hours to Tofino).

Indigenous tour operators lead visitors into their traditional territory, providing a new perspective of local wildlife, plants, and waters:

Guided nature adventures led by the local Nation – Explore Ahousaht territory with Ahous Adventures, which is owned by a nation that has stewarded the lands and waters of Vancouver Island since time immemorial. The popular hot springs tour cruises the coast and inlets of Clayoquot Sound, with guides pointing out wildlife along the way. Once onshore, guests take a 30-minute walk via wooden boardwalk through old-growth rainforest, leading to the healing mineral waters of the hot springs. Throughout the journey, guides will discuss the history and cultural significance of Hot Springs Cove, a site that has been used for centuries by the Ahousat Nation for medicinal and spiritual benefits. Dates: Tours are available throughout summer and beyond.

Cruise an Island Archipelago – Sidney Whale Watching, serving Sidney (just 30 minutes from Victoria, BC) and the Saanich Peninsula on Vancouver Island, is owned and operated by the Tsawout First Nation, with whale-watching experiences taking place on the traditional territories of the W̱SÁNEĆ Nation. The three-hour whale watching tour cruises through the Gulf Island Archipelago, winding past orcas, sea lions, and bald eagles hunting for salmon. Sidney Whale Watching has a 95% whale-sighting rate throughout the year; if guests don’t spot a whale, they are welcome to join another tour free of charge, anytime. Dates: Whale-watching tours take place daily between March and October.

Take a cultural tour in a 35′ canoe – Takaya Tours, based in Whey-ah-wichen, or Cates Park, in North Vancouver, leads guests through the territory of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation. Guests can paddle the protected waters of Indian Arm in replica ocean-going canoes, while guides share songs and stories of ancient villages. There’s also an option to add a rainforest walking tour to your paddling adventure. Dates: The Cates Park location is open between May and September for guided tours, as well as rentals of kayak, surf-skis, and stand-up paddleboards.

BC Tourism Industry Awards Best Indigenous Tourism Operator Winner 2024 – Homalco Wildlife & Cultural Tours, which stewards the grizzly bear population in Bute Inlet—the ancestral home of the Homalco Nation—welcomes visitors to discover the area’s longstanding cultural and historical significance. The company’s full-day bear-watching and cultural tour leads guests to viewing areas that showcase grizzlies feeding on spawning salmon, along with plenty of opportunities to whale watch and bird watch. Guests can also wander through Aupe, an uninhabited Homalco village site. Dates: Tours are offered between August and October.

2023 Yelp Travelers Choice – Sea Wolf Adventures, which leads tours in the Broughton Archipelago and the Great Bear Rainforest, on Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw Nation territory, combines cultural experiences with grizzly- and whale-watching safaris. The Grizzly Bears of the Wild tour connects guests with the iconic grizzly inhabitants of the Great Bear Rainforest, with bonus viewings of Pacific white-sided dolphins, eagles, orcas, and other wildlife. The full-day tour departs from Port McNeill, and includes Indigenous interpretations of local landscapes, as well as stories about the Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw People. Dates: Tours run from May 31 through October.

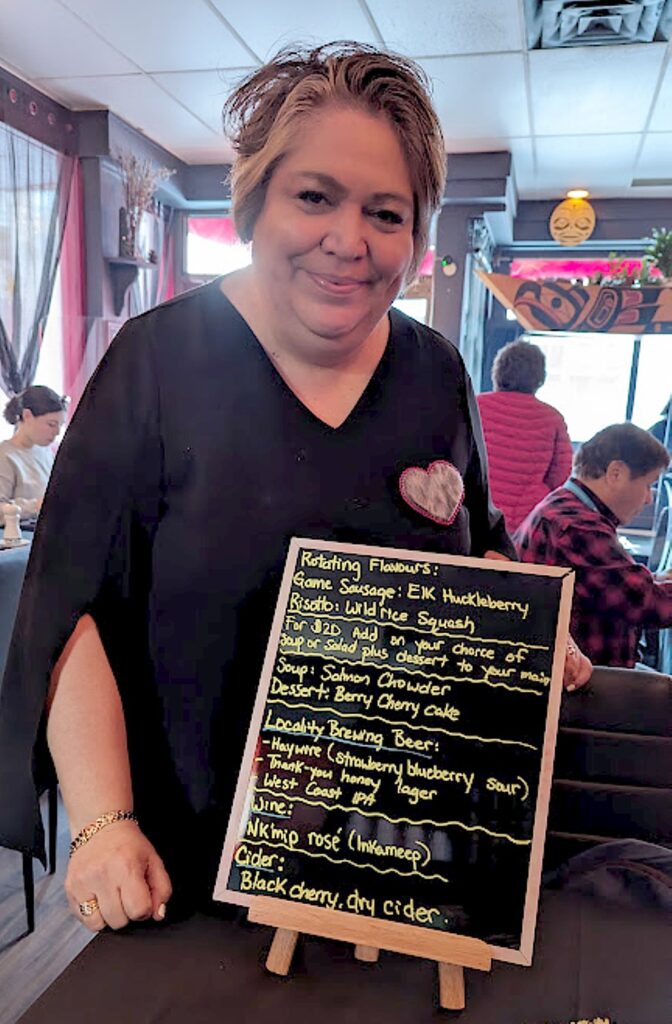

Try Plant Medicine Lemonade – Opened in February 2024, The Ancestor Café in Fort Langley brings traditional Indigenous nourishment to locals and visitors while supporting Indigenous food sovereignty. The eatery is owned by Chef Sarah Meconse Mierau, a member of the Sayisi Dene Nation. On the menu: bison and elk Bannock tacos, handcrafted plant-medicine jams and lattes, and other delicacies made with traditional Indigenous ingredients. Beyond the food, the café features a fair-trade gallery displaying works by local Indigenous artists and brands.

Indigenous-owned and operated accommodation welcome visitors come into their community to experience warm hospitality alongside stories and culture—all with a deep-rooted respect for nature:

Gorge Harbour Marina Resort – One of the most desirable cruising destinations in BC – Located at the edge of Desolation Sound, on Klahoose Nation land, Gorge Harbour Marina Resort offers an idyllic home base for adventurers eager to explore the sound, Cortes Island, and the Discovery Islands. The resort offers a multitude of overnight options, including a rustic lodge with four rooms, a cottage enclosed by lush gardens, and two self-contained trailers. Summer-specific options include 21 full-service RV sites, six glamping domes, and six tent sites—open for the season now. Summer activities span live music on the waterfront, yoga at the harbour, family movie nights, as well as whale-watching tours offered between May 1 and October 15. (Get there: Take a ferry from Vancouver to Nanaimo, then drive 1 hour and 45 minutes to Campbell River. From here, take a 10-minute ferry to Quadra Island, then a 45-minute boat trip to Cortes Island. You can also fly direct to the resort from Campbell River, Vancouver, or Seattle, Washington.)

Nemiah Valley Lodge – Off-grid & highly requested – Open year round, Nemiah Valley Lodge is located in the Chilcotin region, on Tŝilhqot’in Nation land. Here, guests are immersed in the food, history, and traditions of the Xeni Gwet’in community through local events, cultural experiences, and wildlife viewing. The all-inclusive packages include lodge activities such as lakeside yoga and meditation, canoeing and stand-up paddleboarding, fishing, archery. Note: Nemiah Valley is taking bookings for 2025. (Get there: The lodge is a 30-minute floatplane ride from Whistler. Alternatively, take a flight from Vancouver International Airport to Williams Lake (available throughout the summer), and drive 2.5 hours to your destination. The lodge also offers a transfer from Williams Lake.)

Tsawaak RV Resort – A 2024 Indigenous Tourism Award Winner – Whether you’re seeking a cozy wilderness cabin or a place to park your RV, Tsawaak RV Resort— located in Tofino, on Tla-o-qui-aht Nation land—offers a tranquil space for rest and rejuvenation. Guests can choose from 34 RV sites and 13 longhouse-style cedar cabins—all situated close to Mackenzie Beach and a 30-minute walk from town. The central amenities building offers laundry facilities and vending machines, while the visitor center houses an art gallery and retail shop. The resort provides easy access to Tofino’s most popular adventures, including surfing, hot springs, and hiking. (Get there: From Vancouver, fly into Tofino-Long Beach Airport with Pacific Coastal Airlines, or right into Tofino Harbour with Harbour Air. Alternatively, you can take a ferry from Vancouver to Nanaimo or Comox and drive approximately 3.5 hours to Tofino.)

Spirit Bear Lodge – Located in the largest, temperate coastal rainforest in the world – Wildlife viewing and cultural experiences take centre stage at Spirit Bear Lodge, located in Klemtu, on Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation land. The lodge’s all-inclusive adventures are anchored by visits to cultural sites of the Kitasoo Xai’xai People, who have lived for thousands of years in the Great Bear Rainforest—the largest temperate coastal rainforest in the world. Guests can search for the elusive Spirit bear, watch grizzlies roam lush estuaries, see whales and other marine life, and explore the remnants of ancient villages. Open from August to October, with limited reservations available. (Get there: Board a flight at Vancouver International Airport with Pacific Coastal Airlines to Bella Bella. You’ll be met by Spirit Bear Lodge staff and shuttled to the dock, where a lodge boat will take you on the two-hour journey to Klemtu.)

For more authentic Indigenous experiences in British Columbia visit www.indigenousbc.com

Nova Scotia Hosts Worldwide Celebration of Acadian Heritage

This August 10-18, Nova Scotia will host the Congrés mondial acadien (CMA), a worldwide celebration that takes place every five years and brings together the Acadian diaspora from around the world for musical events, culinary and cultural attractions and family gatherings. Several major outdoor concerts featuring noted Acadian artists are scheduled, including Canada’s National Acadian Day on August 15. From the brightly painted houses of Yarmouth and picturesque views of seaside villages like Belliveau Cove and Pointe-de-l’Eglise, visitors will find vivid reminders of the French settlers who first claimed Nova Scotia as their home in the early 1600s. The CMA reunites and welcomes communities, families, and visitors to the province to honor Acadian history and to commemorate the thousands displaced in 1755 when the Acadian people were expelled from the province by the British for not taking a vow of loyalty to King George III. (https://cma2024.ca/en/).

Throughout the summer, there are important Acadian historic sites to visit in Nova Scotia:

Grand Pré National Historic Site: Open from May 17 to October 14, the Grand Pré National Historic Site is a powerful way to discover the history of l’Acadie (a historical Acadian village in Nova Scotia settled from 1682 to 1755), its people and its culture. The location is a monument that unites the Acadian people, and for many, it is the heart of their ancestral homeland. Guided tours lead visitors through the center of this Acadian settlement and where they can learn about the history of the mass deportation of the Acadians, “Le Grand Derangement,” that began in 1755. This tragic event continues to shape the vibrant culture of modern-day Acadians across the globe. Tours are available in July and August.

Le Village Historique Acadien de la Nouvelle-Écosse: Explore the oldest Acadian region still inhabited by descendants of its founder in Le Village Historique Acadien de la Nouvelle-Écosse. Founded in 1653 by Sieur Philippe Mius-d’Entremont, the village is a breathtaking, 17-acre space overlooking Pubnico Harbour. Attractions include historical buildings and original 19th century wooden homes like Duon House and Maximin d’Entremont House, a lighthouse and local cemetery, nature trails with natural fauna and flora indigenous to the area, and opportunities to learn about the historic Acadian fishing and farming traditions.

Rendez-vous de la Baie Visitor Centre: Open year-round and located on the campus of Université Sainte-Anne in Clare, Rendez-vous de la Baie Visitor Centre is an Acadian cultural and interpretive center. Attractions include an artist-run gallery, a souvenir boutique, a 263-seat performance theatre, and an outdoor performance area. Travelers can experience the interpretive center and museum which delve into the Acadian peoples’ history through multimedia displays of music and language with free guided tours available. The venue is also a trailhead for a three-mile network of walking trails leading to the breathtaking Nova Scotian coast (guided walking tours available).

More information: Nova Scotia, www.novascotia.com

New Brunswick’s Acadian Heritage and new Travel Experiences

Another place to experience Acadian heritage is in New Brunswick, just across the strait from Nova Scotia:

Historic Acadien Village is an open air living history museum with costumed (fully bilingual) interpreters who recreate the roles of real people. What makes this place so extraordinary, though, is that you walk a 2.2 km circuit through 200 years of history – the 40 buildings represent a different time, the oldest from 1773 up to 1895, then, you walk through a covered bridge built in 1900 into the 20th century village where the buildings date from 1905 to 1949. As you walk about, you literally feel yourself stepping across the threshold back in time.

You not only visit but can actually book a room to stay at the Hotel Chateau Albert (1910). Albert opened hotel in 1870 but had financial problems from the beginning and was put out of business by Canadian Pacific railroad.. The building was destroyed in a fire in 1955, and restored using the original plans. It now offers 14 rooms (with bathrooms) that you actually can book to stay overnight. (hotelchateaualbert.com, 506-726-2600).

Historique Acadien Village, 5 rue du Pont, Bertrand, NB, 1-0877-721-2200, [email protected], villagehistoriqueacadien.com

Also in New Brunswick, Metepenagiag is an active archaeological site and research center where artifacts unearthed have provided proof the Mi’kmaq have been occupying this land for at least 3,000 years. When you first walk into the exhibition building, you can look into the lab where researchers examine artifacts. Some of the items, like a 1200-year old Earthenware pot, arrowheads and other items are on display.

What is more, you can overnight in a tipi (glamping), cabin or lodge, have a First Nations dining experience, storytelling and be immersed in the 3,000-year heritage around a campfire. Or take part in “A Taste of Metepenagiag” and learn about foods and cooking techniques. New experiences are also being developed.The Mi’kmaq operate SP First Nations Outdoor Tours, authentic indigenous experiences that begin with a traditional welcome, a river tour by canoe or kayak, storytelling; and authentic First Nations dining and accommodations (56 Shore Road, Red Bank NB, Metepenagiag, 506-626-2718).

Metepenagiag Heritage Park, 2156 Micmac Road, Red Bank NB, 506-836-6118, [email protected] 1-888-380-3555, metpark.ca.

In 2024, New Brunswick, the Atlantic Canadian province just over the Maine border, unveils novel experiences for visitors including new ways to explore the capital city of Fredericton, dining the bottom of the ocean floor at the Bay of Fundy, a revitalization of a favorite gathering spot in Canada’s oldest city, Saint John, and 60th anniversary celebrations of the FDR International Park on Campobello Island.

Dining on the Ocean Floor: Visitors to Hopewell Rocks Provincial Park this year can not only observe the natural phenomenon of low and high tides alternating as much as 40-plus feet, they can also dine on the ocean floor. In 2024, Hopewell Rocks will offer its new culinary adventure: “Dining on the ocean floor”. Travelers will relish in the magic of dining among some of the most extraordinary rock formations in the world with a private, locally sourced three-course meal and specialties served from Magnetic Hill Winery in Moncton. After enjoying cuisine by the sea, park-goers can return the next day at no additional admission cost, which starts at $15.85 CAD, to behold both high and low tides. For more information about Hopewell Rocks Provincial Park and updates about dining on the ocean floor, visit https://www.thehopewellrocks.ca/.

Coffee Connoisseur Tour with Barista Brian: Home to top attractions like Odell Park, Boyce Farmers Market, and Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, New Brunswick, is also an ideal location for coffee lovers wishing to expand their knowledge and taste buds. For a new way to explore the city, visitors can join internationally celebrated latte artist Barista Brian on the new “Coffee Connoisseur” walking tour. Brian has earned his title while decorating lattes for attendees of the Sundance and Toronto International film festivals and for multiple Hollywood celebrities. Participants will sip, savor, and learn about locally roasted coffee at four independent coffee shops in the capital. Barista Brian is famous for his renowned latte art creations and has produced multiple latte portraits of celebrities including Meryl Streep, Conan O’Brien, Jennifer Lopez, Kristen Stewart, and more. While touring, Brian will provide education about everything from single origin beans to sustainable coffee, the history of coffee, and how to properly taste. Attendees will enjoy tastings of several coffee drinks such as a blend, delicious espresso, single roast, and will finish off with a latte displaying the handcrafted art of Brian. For more information about Barista Brian and his work, head to https://www.baristabrian.com/. To purchase tour tickets and view available dates, https://www.eventbrite.ca/e/coffee-connoisseur-tour-with-barista-brian-tickets-764462898107.

Campobello Island’s FDR International Park Celebrates 60th Anniversary: A symbol of international cooperation, the Franklin D. Roosevelt International Park on Campobello Island is jointly administered, staffed, and funded by the people of Canada and the United States. In 2024, the landmark is celebrating its 60th year standing as a representation of global collaboration. Throughout the month of July, special anniversary festivities will unfold amidst the breathtaking views of the New Brunswick Island connected to Maine by bridge. The former U.S. president and his family would spend their summers on Campobello Island, and visitors can now experience the former 34-room summer mansion firsthand. Given as a wedding gift to Franklin and Eleanor in 1908 by Franklin’s mother Sara Roosevelt, the cottage quickly became a key piece of the couple’s beloved island. Activities include “Tea with Eleanor” in the backyard and guided tours. For further details and event updates, visit https://www.rooseveltcampobello.org/.

Market Square Boardwalk Revitalization: In Uptown Saint John, Canada’s oldest incorporated city, the Market Square Boardwalk will show off a new look in 2024. It is now known as Ihtoli-maqahamok (The Gathering Space), chosen through a community process between Saint John citizens, the Civic Commemoration Committee, Common Council, City of Saint John staff, and consultation with First Nations’ leaders from The Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick. The boardwalk has undergone a rejuvenation that includes a larger 360-degree stage with increased public space for live performances, tidal steps leading to the Bay of Fundy, and the installation of a winter outdoor skating surface that will convert to a verdant green space in the summer. The restaurants of Market square were also upgraded with glass-panel installations, creating patios with year-round dining. Ihtoli-magahamok (The Gathering Space) draws its design inspiration from the three foundations of Saint John: its people, the water, and the rugged rocks that define the city’s character. To learn more about the reimagined Market Square Boardwalk, head to https://saintjohn.ca/en/parks-and-recreation/ihtoli-maqahamok-gathering-space

Travel planning assistance from Tourism New Brunswick, 800-561-0123, www.tourismnewbrunswick.ca.

Summer is a 5 Sensory Season in Newfoundland and Labrador

From the rolling waves lapping off the coastline to the colorful clotheslines dancing in the ocean breeze, Newfoundland and Labrador is home to the slow way of life, especially when the seasons change. As spring rolls into summer, regular visitors to the province return, including the whales, birds and icebergs that heighten all senses. Visitors can experience the first sunrise in North America, witness the migration and play of whale species that return to the shores each year, and taste food foraged from land and sea. For relaxation, guests can soak in the bounty of the ocean in a bath with seaweed gathered off the coast of Grates Cove, go for a cold-water dip in the many outdoor locations including the North Atlantic Ocean, or sit and listen to the push and pull of the beach rocks as they roll with the waves.

Sea of Whales Adventures: The Atlantic Ocean surrounding Newfoundland and Labrador boasts as many as 22 diverse whale species. Just off the Bonavista Peninsula, travelers will smell the ocean breeze and be humbled by the spectacle of whale species like humpbacks, sperm, orcas, feeding, migrating, and playing on Sea of Whales Adventures whale watching boat tours. Family owned and operated since 2009, Sea of Whales Adventures offers three-hour whale watching tours daily from May 15 to October 14 and two-hour tours daily from June 15 to September 3. The two-hour tour rates start at $90 CAD for adults and $60 CAD for children, while the three-hour tour rates start at $110 CAD for adults and $80 for children.

Preserving the Dark Sky: Terra Nova National Park, the first designated Dark Sky Preserve in the province, allows travelers to gaze into the cosmos untouched by light pollution. Under the Dark Sky Preserve Program, the park is committed to protecting and improving nocturnal ecology by adjusting, retrofitting, or eliminating light fixtures while delivering new educational and interpretive programs on astronomy and various dark sky themes. The most popular viewing locations include Sandy Pond, rated to have the darkest skies in the park, Ochre Hill, historically used as a fire-watch station, Blue Hill, the highest point in the park putting guests among the stars, and Visitor Centre, with the starlit sky reflected across the water. New in 2024, UNESCO World Heritage Site Gros Morne National Park is applying to the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada for designation as a Dark Sky Preserve, offering visitors even more unaltered space to bask in the celestial views.

Wild Island Kitchen: Open year round, Wild Island Kitchen offers travelers the chance to dine aside breathtaking seascapes listening to the crashing waves while wild and sustainably caught seafood is cooked over an open fire. The locally owned tour and culinary group provides menus that change daily based on what is foraged and discovered each day, with guides teaching guests how to cook and prepare the cuisine. The “From Sea to Plate” Tour features sustainable, high-quality seafood cooked with water from the sea and cooked over an open fire, and guests can expect four to five courses over a three-hour period. For a shorter, one-hour experience, visitors can book the “Mug-Up” Tour which typically departs at 10 a.m. and includes a trip down the cove for a cup of tea or coffee and an interpretative food journey inspired by traditional coastal delights. Tour rates start at $175 CAD, but guests are encouraged to email [email protected] for specific pricing per tour. Pre-booking is required for both culinary experiences.

Grates Cove Seaweed Baths: In the northernmost part of Newfoundland and Labrador, weary travelers can soak in a seaweed bath at Grates Cave Co. Known for its healing and rejuvenating properties, seaweed is harvested off the coast of Grates Cove and transformed into 7 Fathoms skincare, producing a high-quality, highly bioactive brown seaweed extract suited for personal care. Grates Cove Co. uses the product, densely packed with essential nutrients and minerals, for the fresh seaweed baths in the comfort of the bathhouse overlooking the North Atlantic. The bathhouse is bookable from Monday to Sunday for two-hour time slots from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m., 2-4 p.m., and 5-7 p.m., and the price per couple is $110 CAD + HST (Harmonized Sales Tax).

More information: Newfoundland and Labrador, www.newfoundlandlabrador.com

See also:

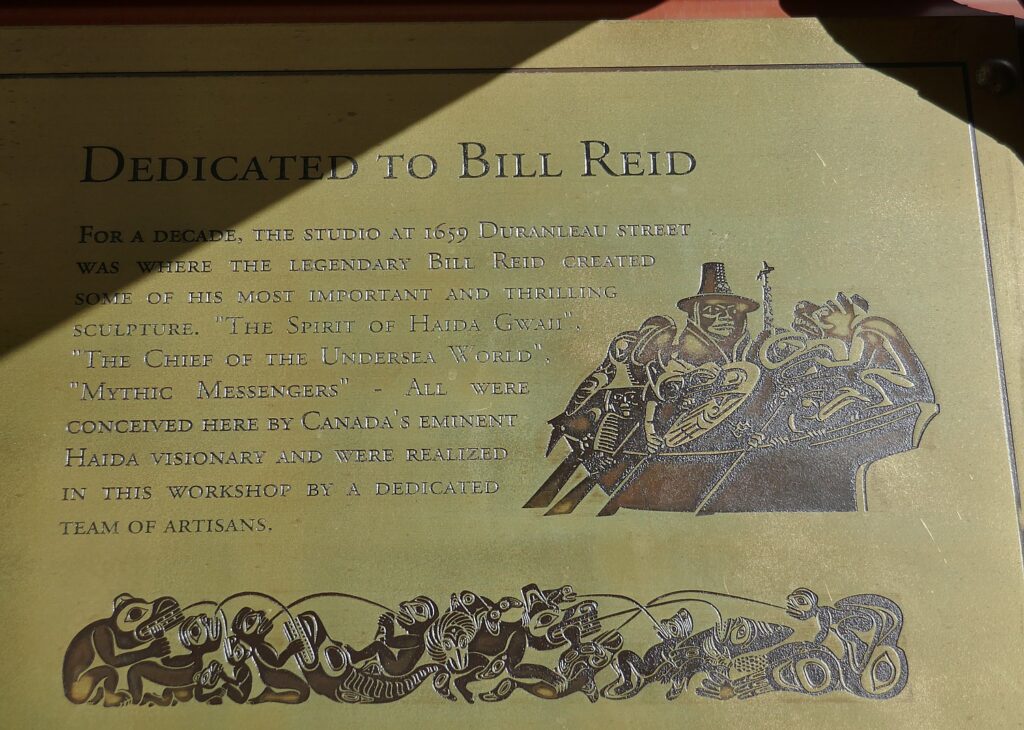

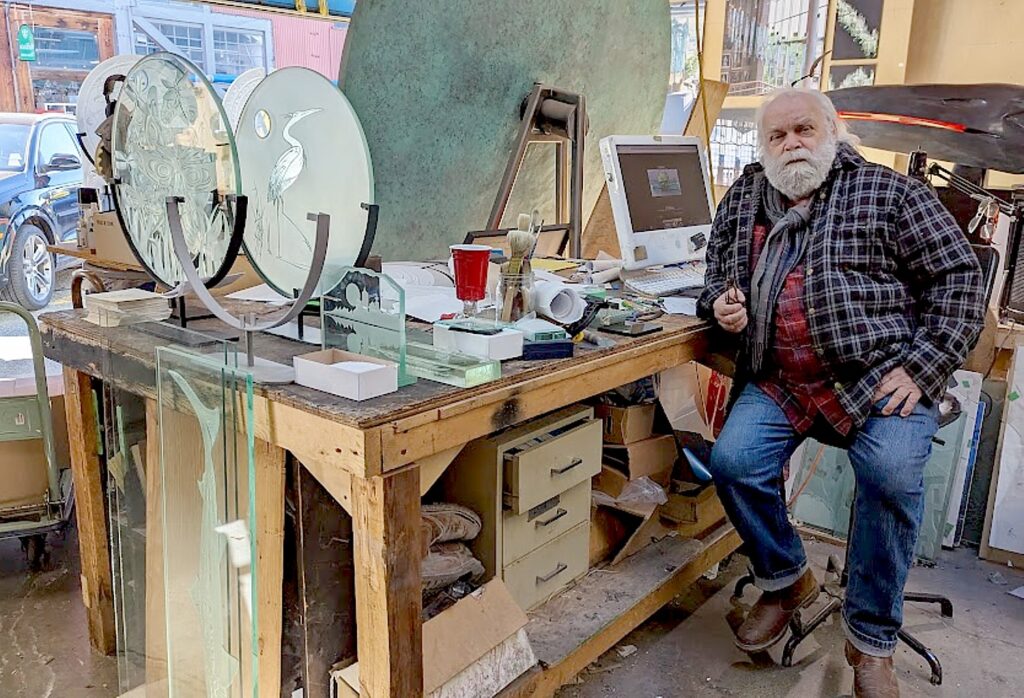

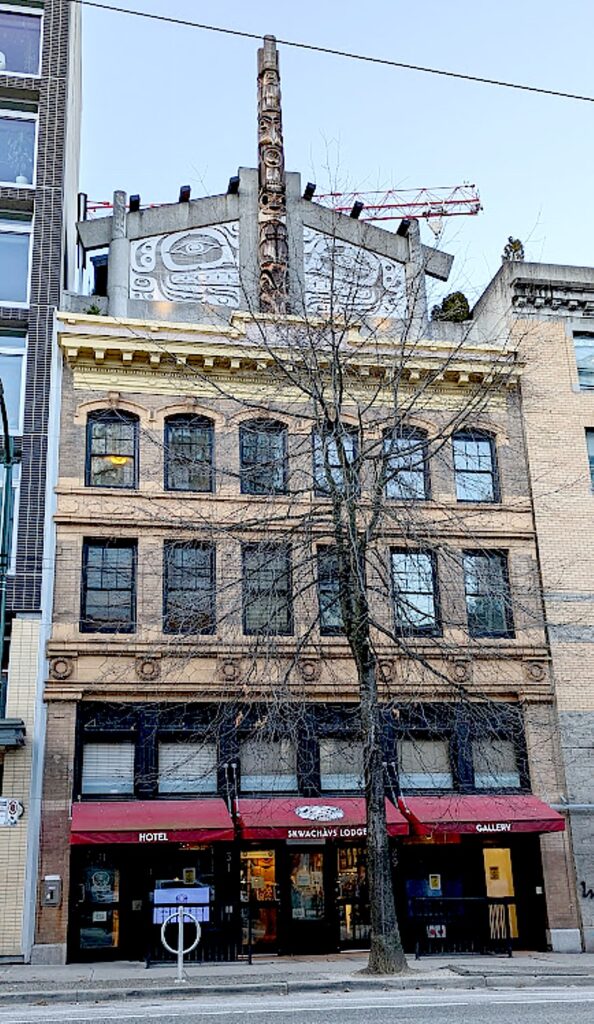

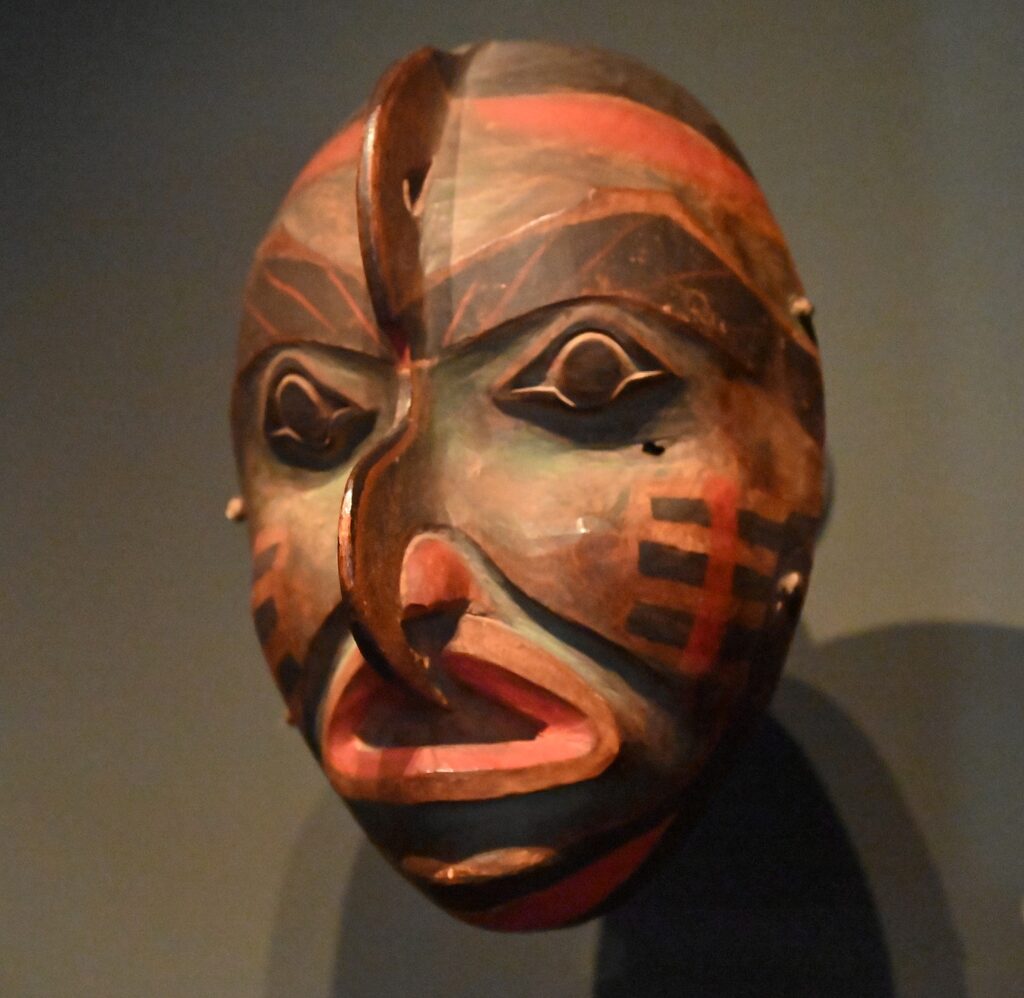

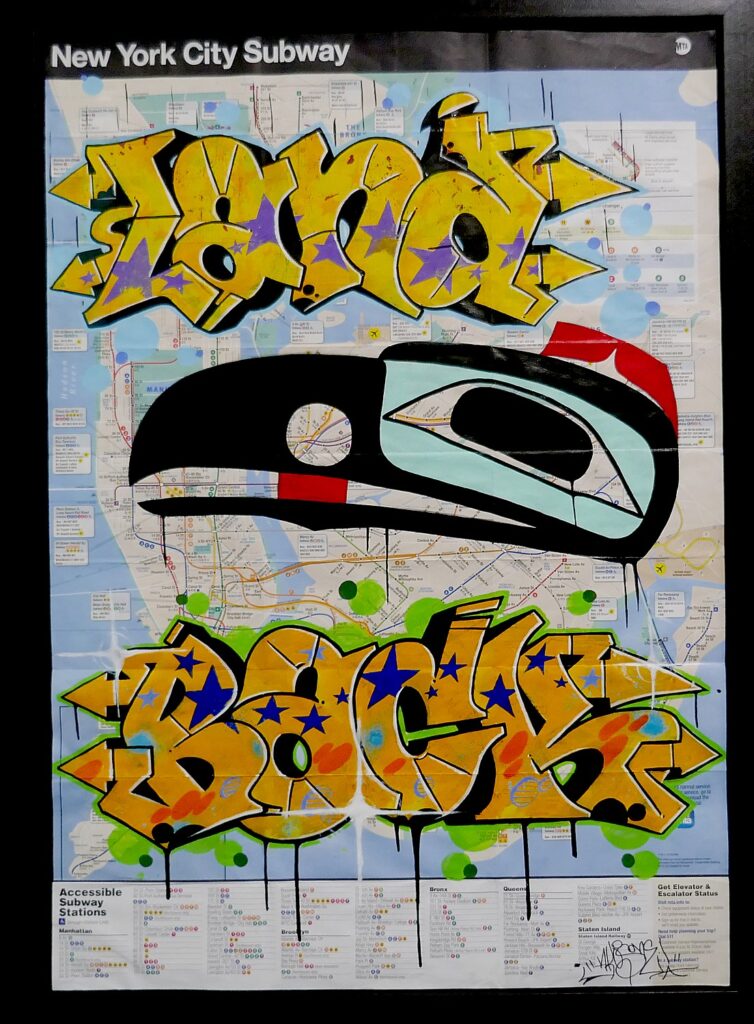

ON THE TRAIL TO DISCOVER VANCOUVER’S REVIVED INDIGENOUS HERITAGE

WALKING TOURS, DINING EXPERIENCES REVEAL VANCOUVER’S REVIVED INDIGENOUS HERITAGE

TRAIL TO DISCOVER BRITISH COLUMBIA’S INDIGENOUS HERITAGE WEAVES THROUGH WHISTLER-BLACKCOMB

NEW BRUNSWICK ROADTRIP: EXPLORING FRENCH ACADIA’S CULTURE, HERITAGE BY BIKE!

NEW BRUNSWICK ROADTRIP: METEPENAGIAG HERITAGE CENTER HIGHLIGHTS MIRAMICHI VISIT

________________

© 2024 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to [email protected]. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us atfacebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures