By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

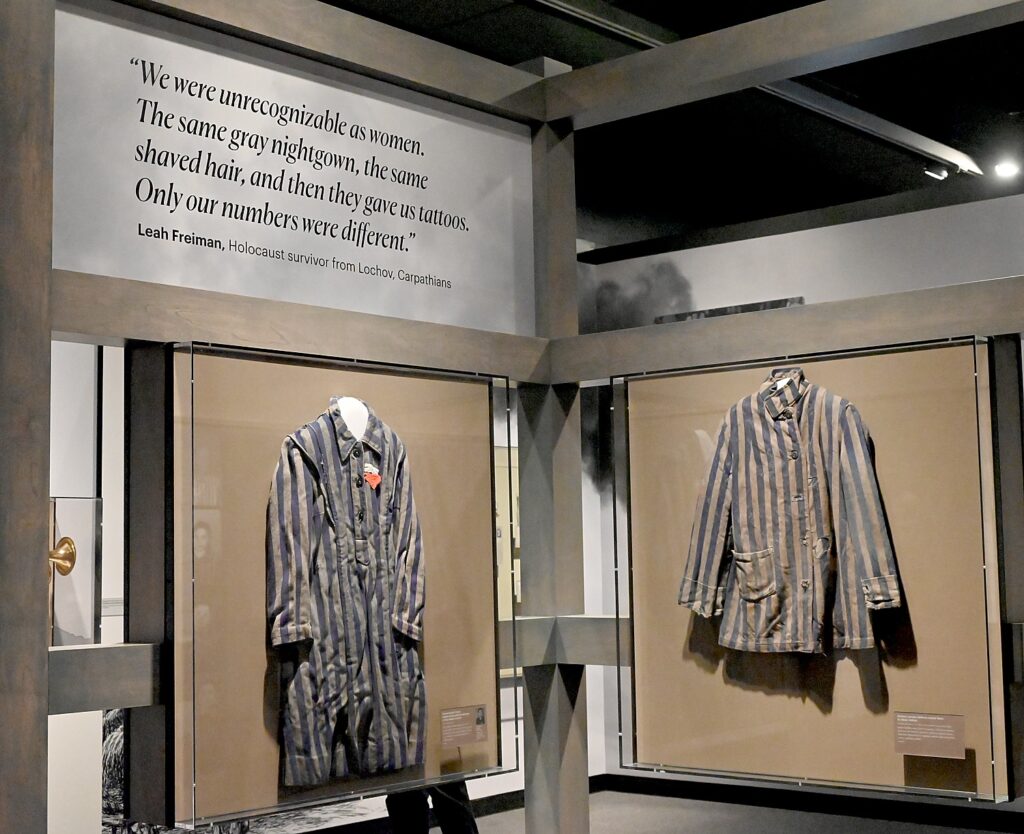

It is surreal, extraordinarily intimate, overwhelmingly emotional to find yourself standing in Anne Frank’s tiny room exactly as she had lived in it, in secret hiding for two years, just before she was taken away by Nazis to the concentration camp where she died just a few months before she would have been saved.

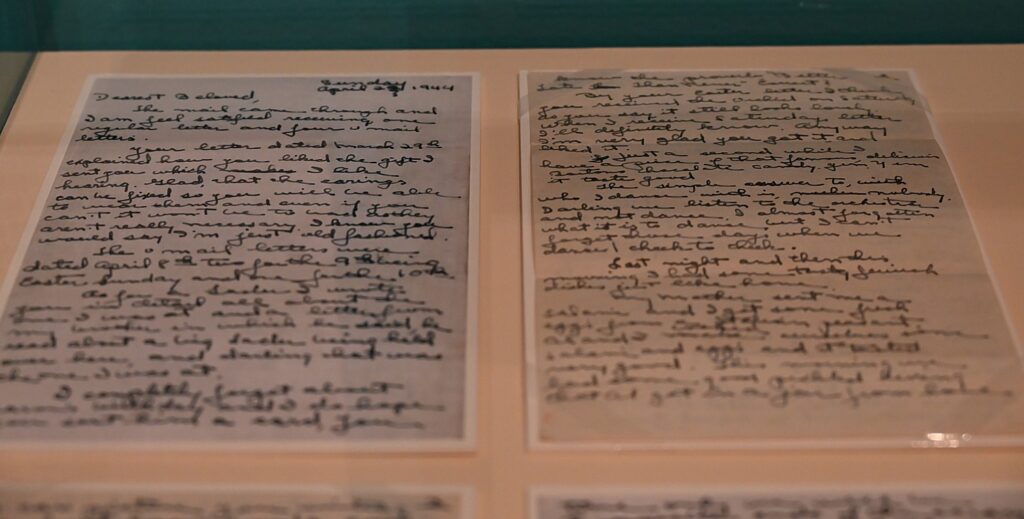

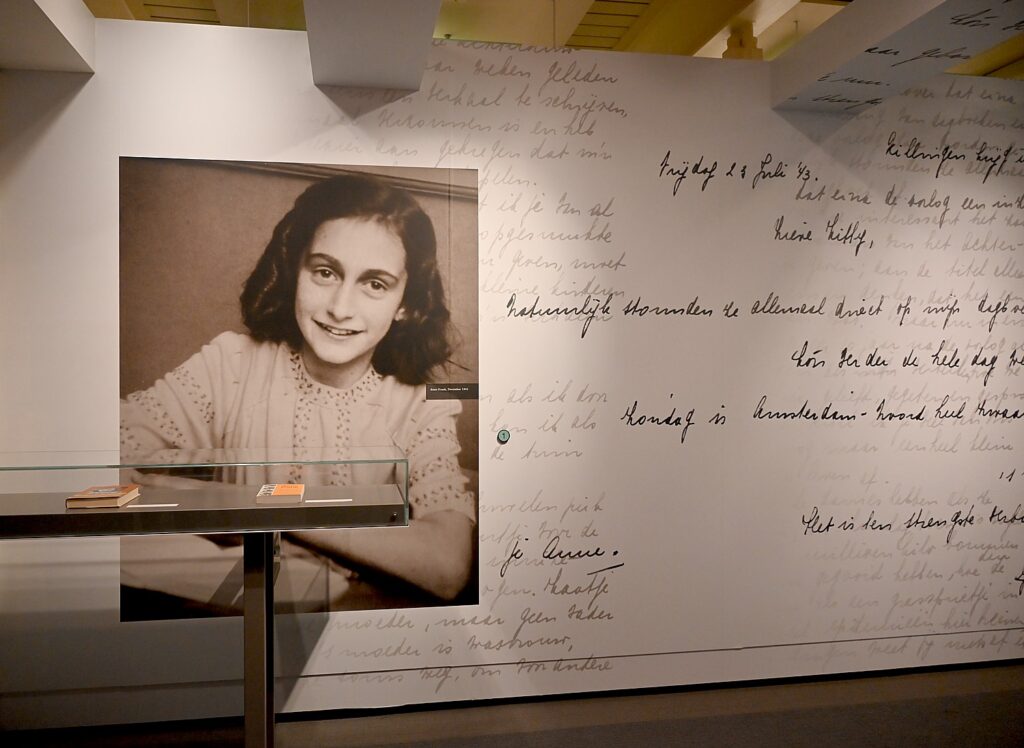

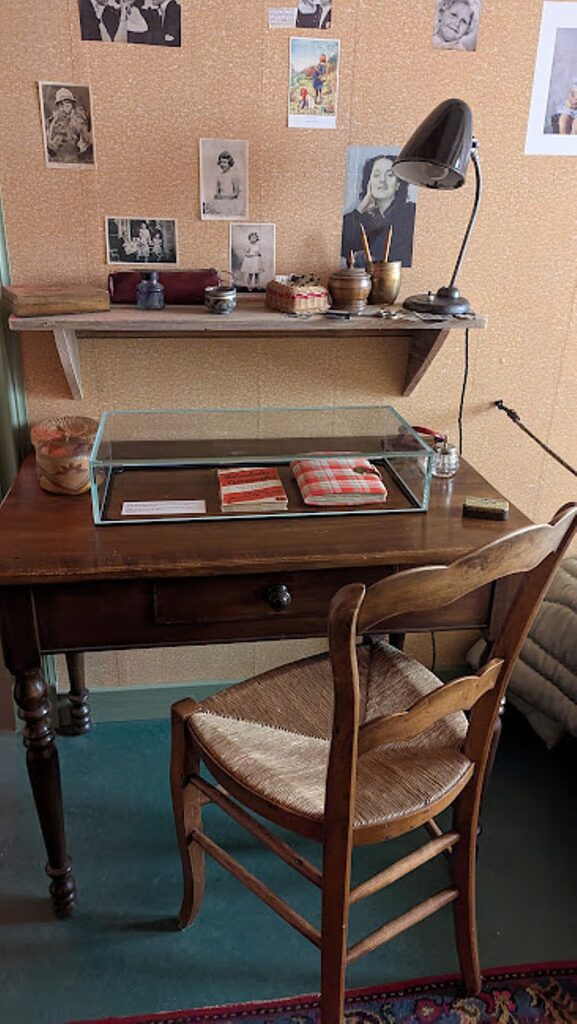

There are the photos she clipped from newspapers to put on her wall, to preserve some connection to a normal life, her life before the Nazis took over Germany, then invaded the Netherlands, where her family had sought refuge. You see the plaid-cloth covered diary she began to write the day she received it, on her 13th birthday, who she sometimes wrote to as “Dear Kitty” and treated as her closest friend and confidant, revealing things her father later admitted he never knew about his daughter despite being close and living in such constant proximity.

As you stand in this space, the tiny bedroom where she sat at this desk to write, you hear her words, “When I write, I can shake off my cares, my sorrow… my spirits soar…. But will I ever be able to write something great? Will I ever be able to be a journalist or writer? Oh, I hope so.” And then, “Writing allows me to record everything – thoughts, ideals, fantasies.”

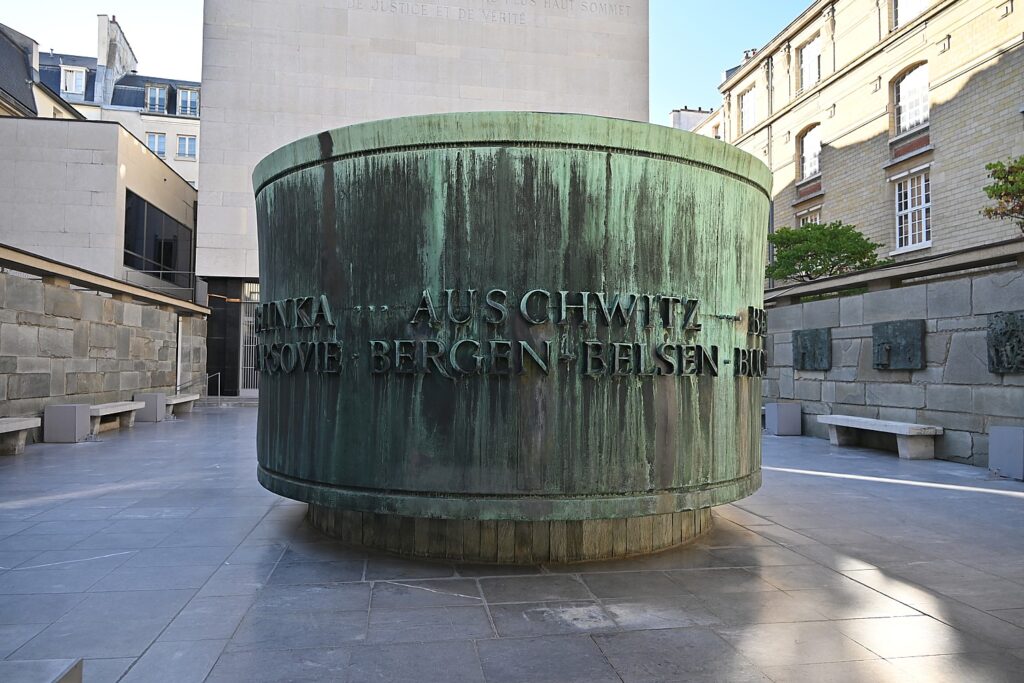

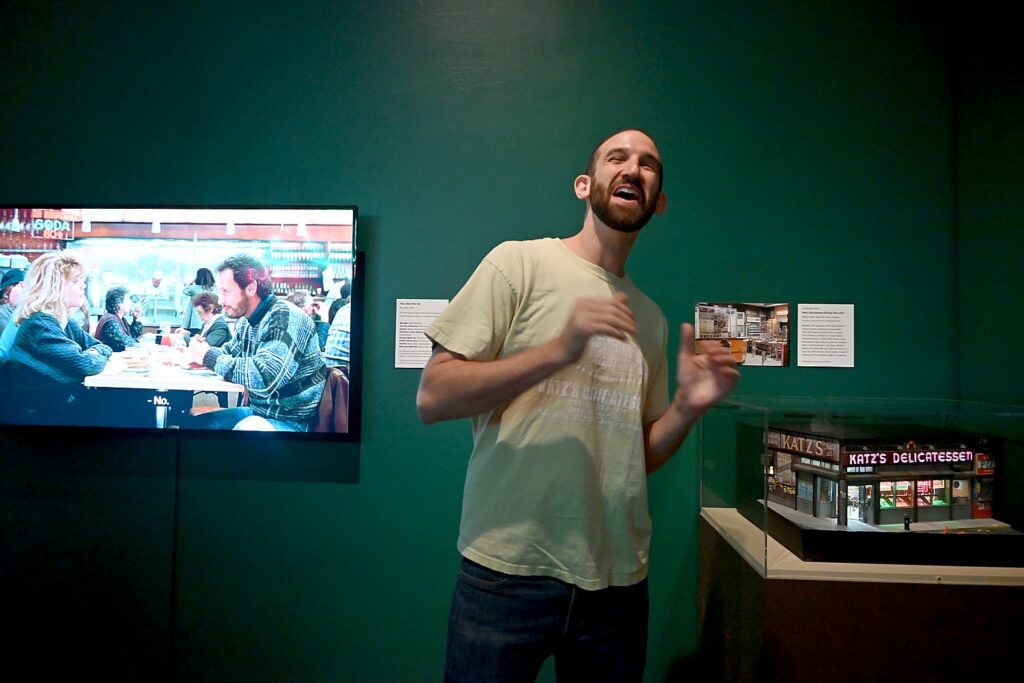

This is the remarkable Anne Frank The Exhibition, opening at the Center for Jewish History in New York City on January 27, coinciding with International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp where one million Jews were exterminated.

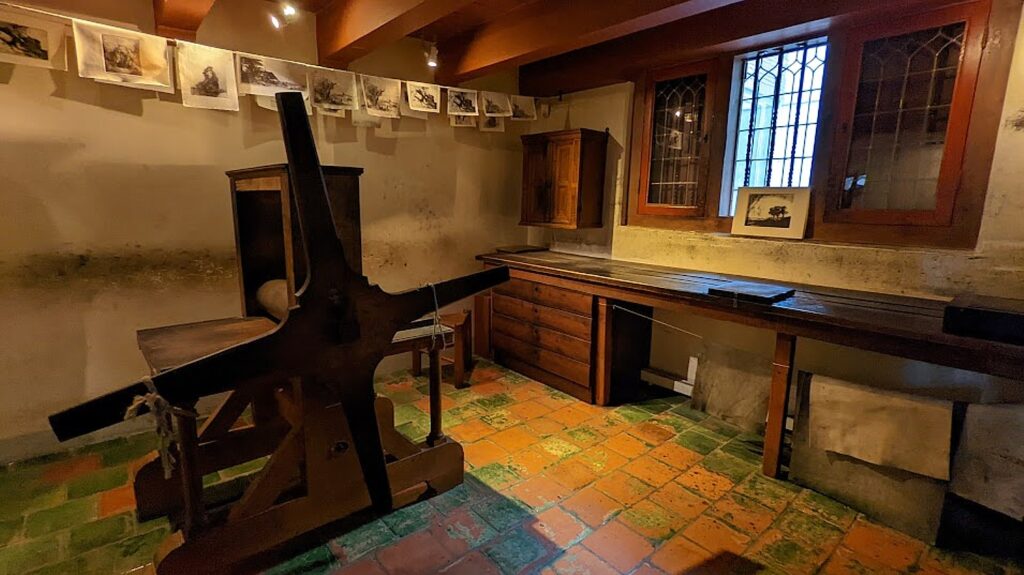

For the first time, visitors outside of Amsterdam will be able to experience the Anne Frank House, one of the most visited historical sites in Europe, but in a very different way: whereas in Amsterdam, the rooms are empty as they were after the Nazis left it, here, visitors are immersed in a full-scale re-creation of the complete Annex, furnished as it would have been when Anne and her family and four other Jews spent two years hiding to evade Nazi capture.

You see the pictures clipped from newspapers she put on her wall – a semblance of normalcy of a teenager. You hear her words from her diary as you walk through those rooms.

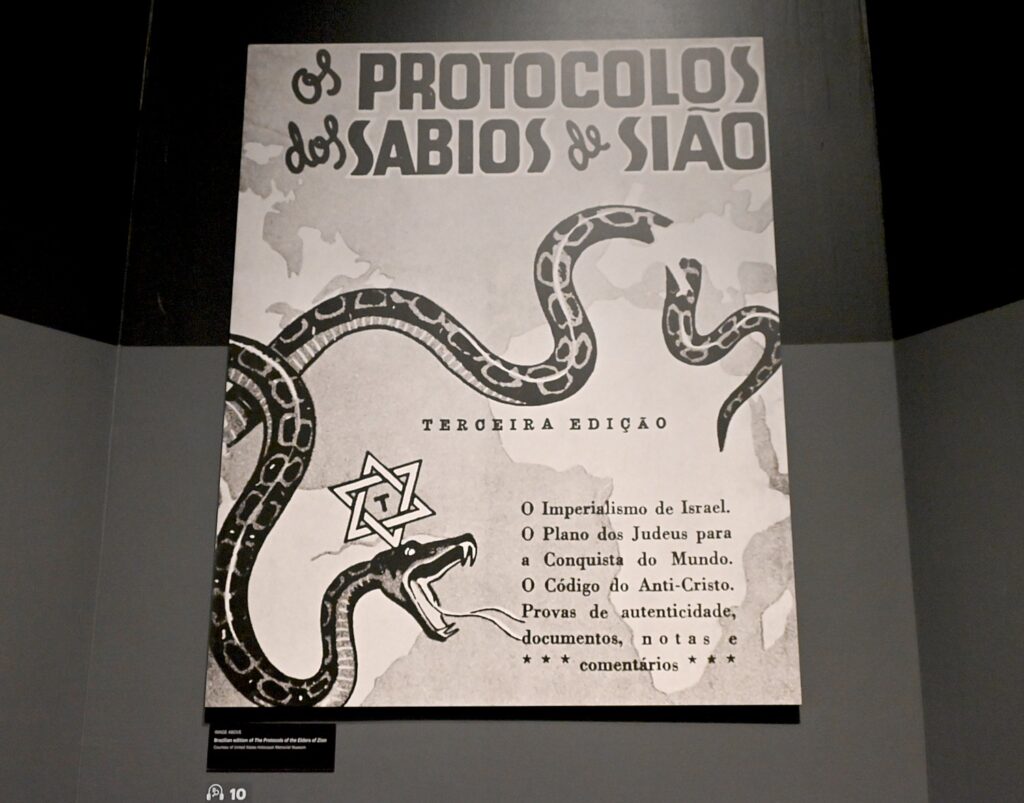

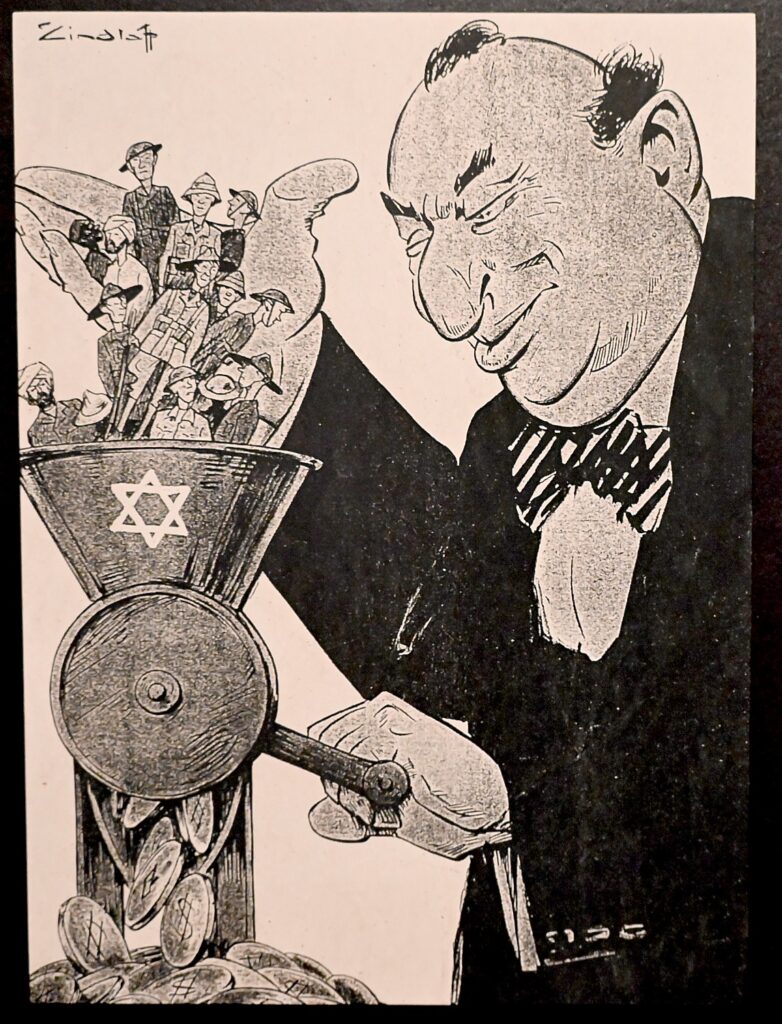

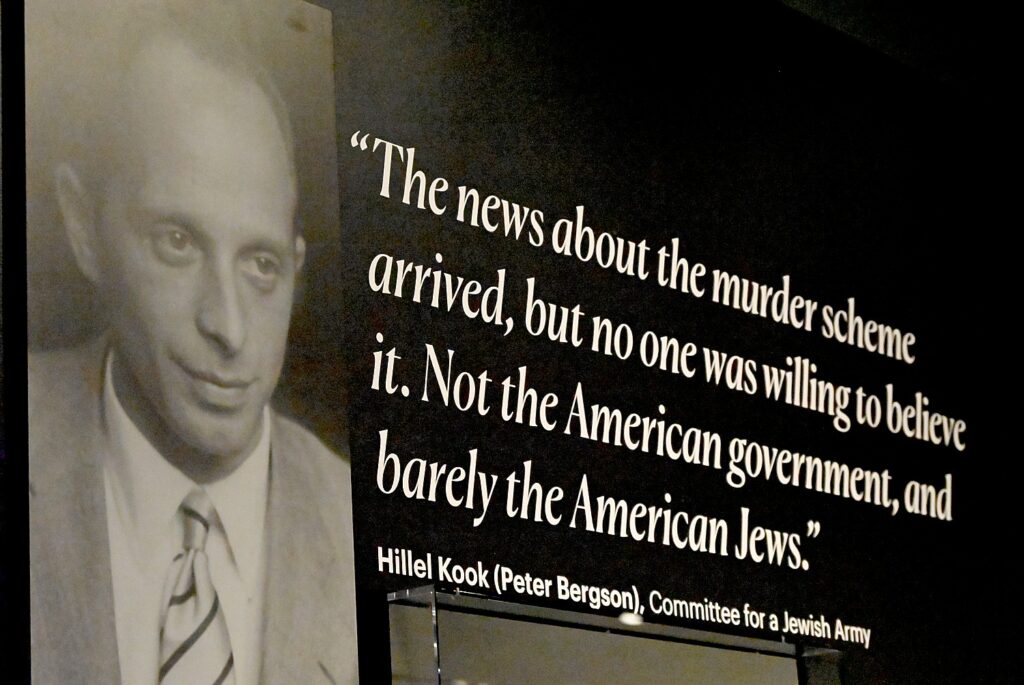

But there is another important difference: before and after you roam through this meticulously re-created Annex, you are immersed in her life and the lives of millions of others as you see the rise of Hitler and the Nazis, how the Holocaust was set into motion and what it was like to live with such terror– giving a broader context and meaning to Anne Frank’s story, resonating with chilling effect today.

Created in partnership between the Anne Frank House and the Center for Jewish History, this astonishing, Anne Frank: The Exhibition kicks off the Center‘s 25th anniversary season.

“We are absolutely thrilled to partner with the Anne Frank House on this landmark exhibition,” said Dr. Gavriel Rosenfeld, President of the Center for Jewish History. “As we approach the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in January, Anne Frank’s story becomes more urgent than ever. In a time of rising antisemitism, her diary serves as both a warning and a call to action, reminding us of the devastating impact of hatred. This exhibition challenges us to confront these dangers head-on and honor the memory of those lost in the Holocaust.”

The exhibition, he said, “dovetails with CJH’s mission. We don’t just preserve Jewish history, we mobilize to address today’s challenges. Public programs foster understanding in a world that needs it more than ever.”

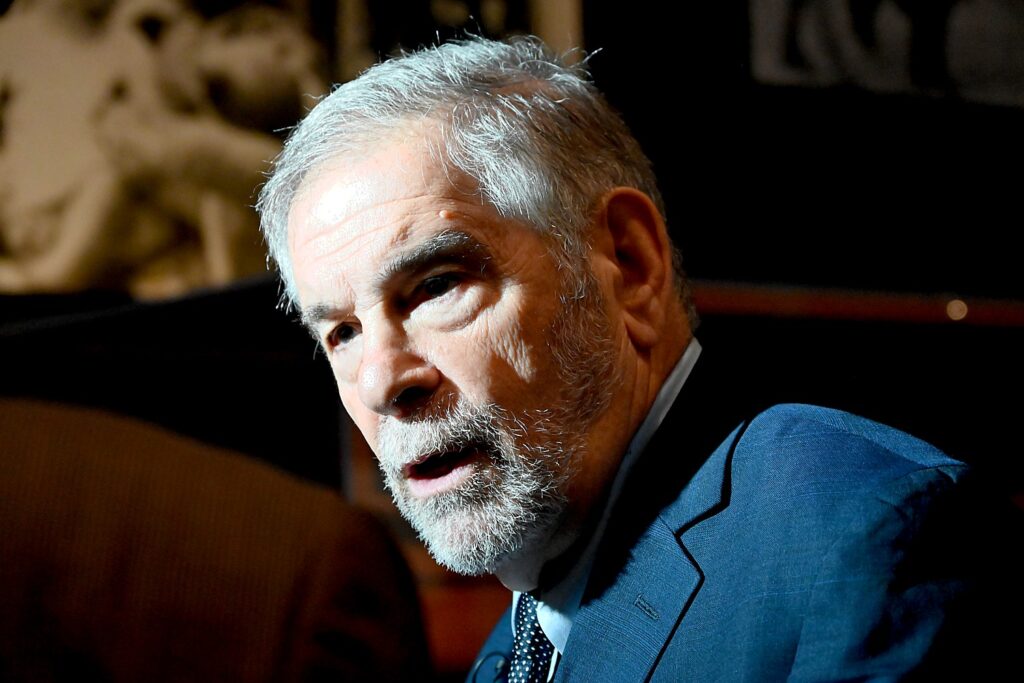

“When students learn to identify hate, learn to confront with empathy, critical thinking, they will champion justice and equality,” Ronald Leopold, the director of the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, said at the press preview. “An exhibition like this serves as powerful reminder of the importance of confronting hate through education and understanding.

“The exhibition is a beacon of remembrance, of education, of awareness. It arrives at a very critical moment. We are living in a time when antisemitism and other forms of group hatred are on the rise, not only in this country, but my country, the Netherlands, and around the globe.” He referred to terrible incidents as recently as the day before, in Sydney, Australia.

“Anne Frank’s story is known to many but what you will experience at this exhibition goes beyond her tragic fate. The exhibition hopefully will also offer a deeper, multifaceted view of who Anne Frank was- not just a victim of the Holocaust, but just a girl, a teenager, a writer, and an enduring symbol of resilience and strength.”

The Anne Frank House, was established in 1957 in cooperation with Otto Frank, Anne Frank’s father, as an independent nonprofit organization entrusted with the preservation of the Annex and bringing Anne’s life story to world audiences in order to serve as a place for teaching and learning about the Holocaust. Each year, the Anne Frank House, welcomes 1.2 million visitors, but many are turned away (you have to reserve tickets weeks, even months in advance), and requires visitors to come to Amsterdam.

“This exhibition is not just about the past,” Leopold said at a press preview. “It is important to learn about the past, but more important to learn from the past. That is the educational mission Anne’s father, the only one of the 8 Jews in hiding at the Annex who survived, gave us when Anne Frank House opened to the public in 1960.”

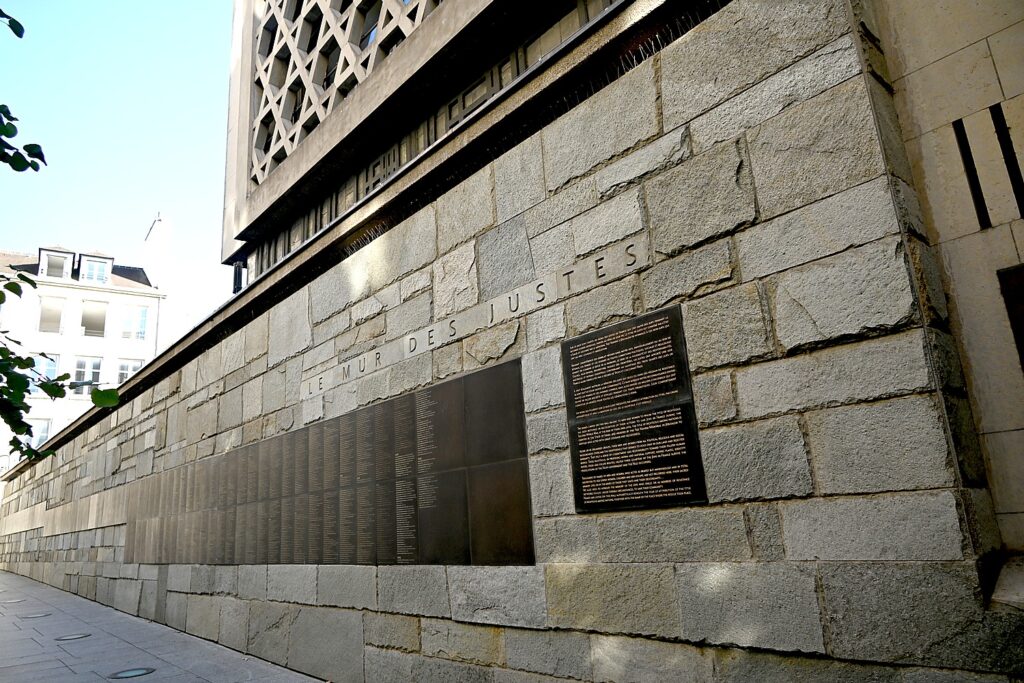

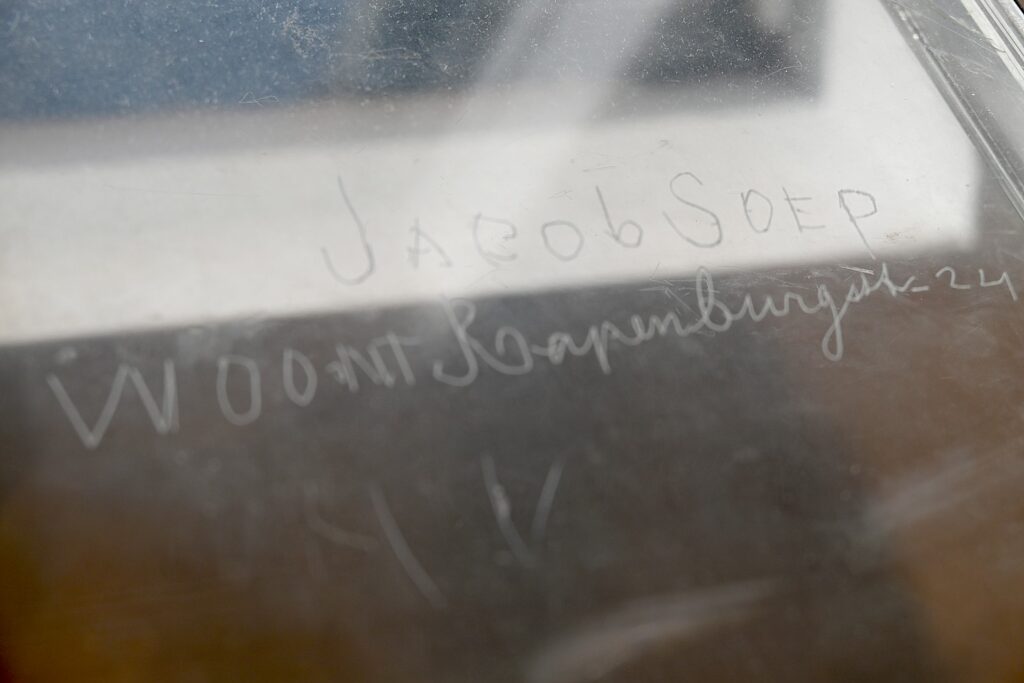

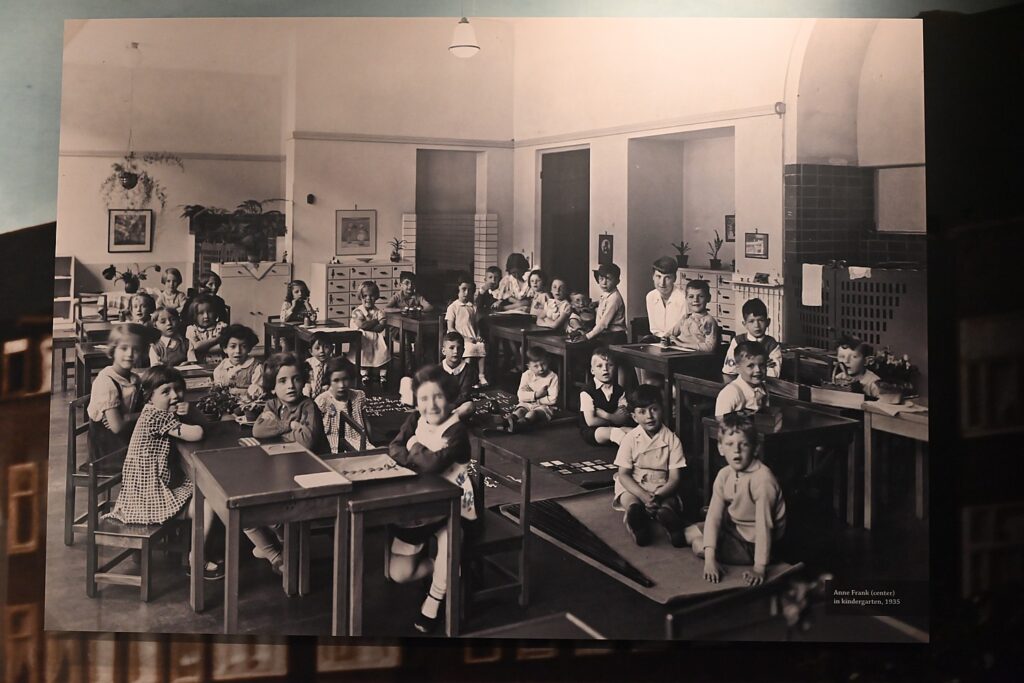

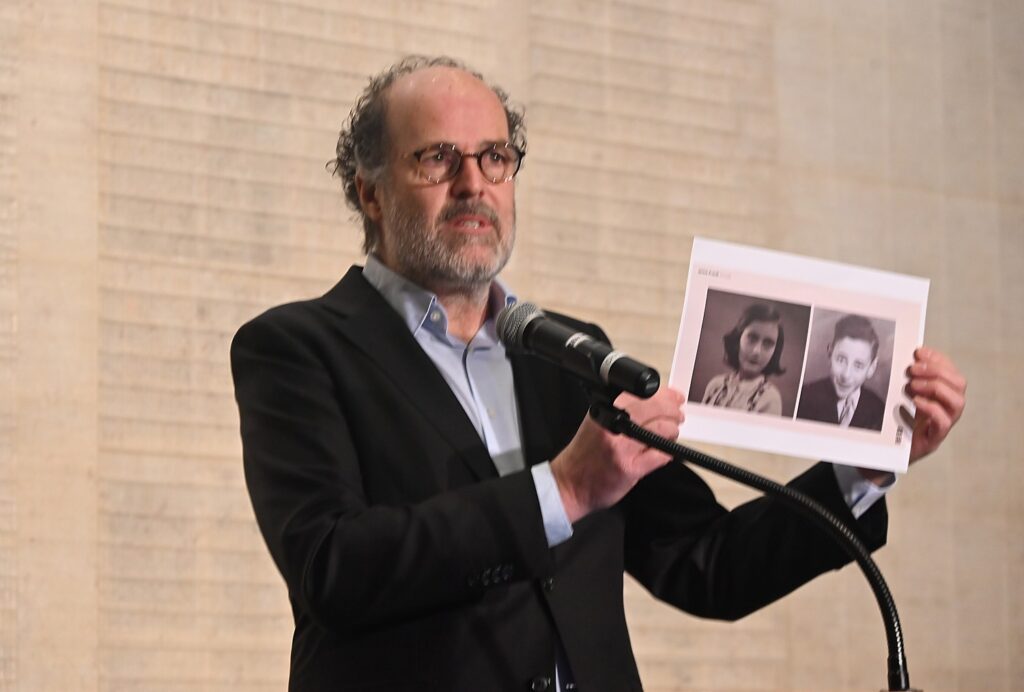

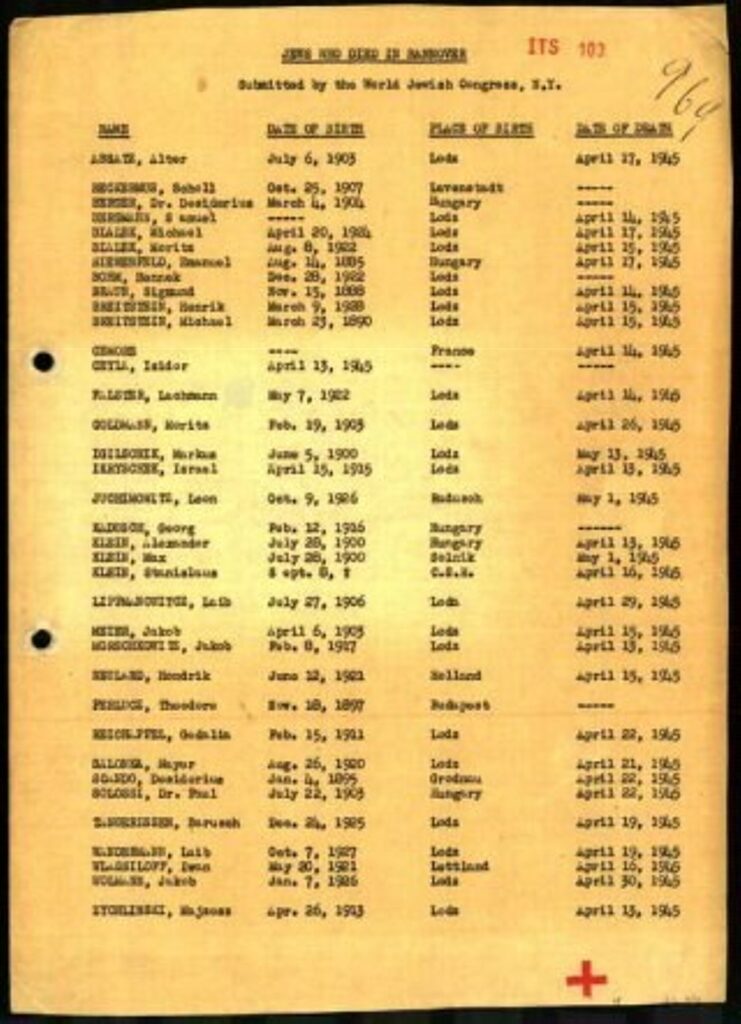

Leopold held up two photos, side by side. One is easily recognizable: Anne Frank. Next to her on the page is a photo a boy no one has heard of. He was born June 12, 1929, the same day as Anne, lived one block from where she lived, a 3 minutes walk. Their paths might have crossed – we don’t know. We know everything about this little girl, Anne Frank, we think, but there is no one in the world today who knows anything about this young boy except for his name, David Spanyeur, his date of birth, address and when and where he was murdered, on February 12, 1943 in Auschwitz.”

“If we bring Anne Frank to New York, and we go to remember her on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we also bring, David Spanyeur to New York, and remember him, as we will remember 1.5 million Jewish children’s lives cut short by human beings for the single reason they were Jewish. This is the message we try to bring, that goes beyond Anne Frank.

“We will remember David Sponyeur, we will remember Anne Frank, may their memories be a blessing. As we stand in presence of Anne’s legacy, we are reminded of our shared responsibility to carry this message forward.”

Philanthropic support has made it possible for the Anne Frank House to subsidize visits for students from New York City public schools and all Title 1 public schools throughout the United States. A special curriculum has been created for distribution to 500,000 children, and there is a 28-minute film at the center that is geared to school children.

So far, tens of thousands of already purchased tickets in advance of the opening; 150 schools have already scheduled visits from as far as California.

A Normal Teenager

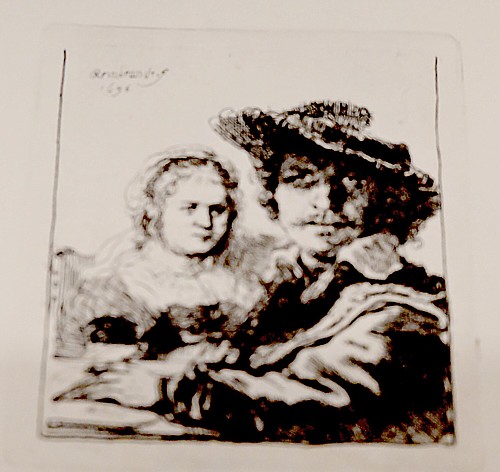

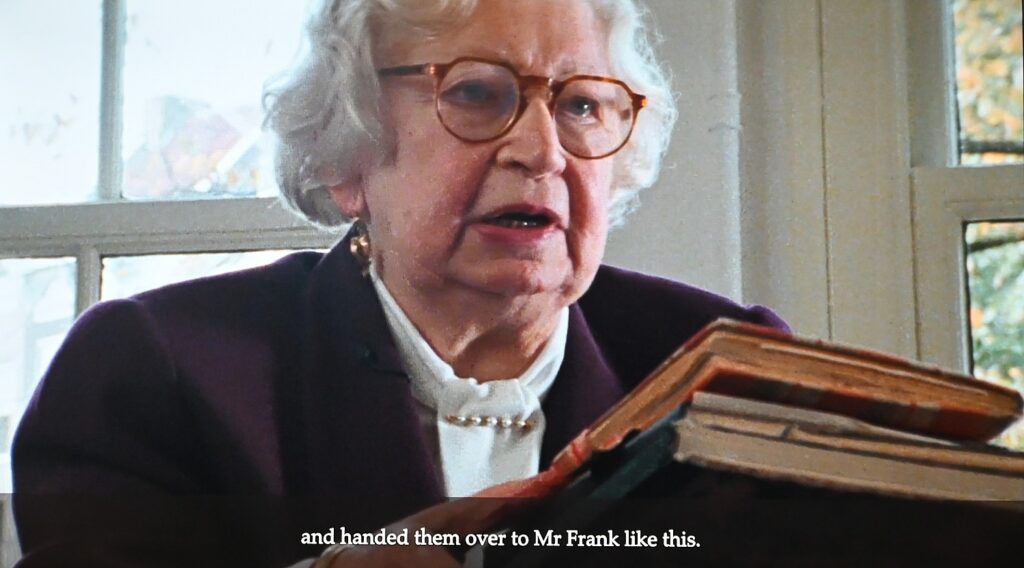

Anne Frank was one of 1.5 million children murdered in the Holocaust – who, like Anne, had dreams, talents, hopes that were snuffed out. Anne is the one who is most and best known because of the sheer miracle of her keeping the diary and her journals being saved, Miep Gies, one of the people who protected the Franks in the Annex, finding it after the Nazis had ransacked their rooms, and keeping Anne’s writings safe because she knew how much writing meant to her, then reconnecting with Otto Frank, who was determined to fulfill his daughter’s dream of becoming a published writer, then a publisher recognizing how important the diary was because too many did not see the commercial value, or perhaps, the political correctness.

There is so much that is astonishing about this exhibit – certainly being able to stand in this exact, full-scale re-creation of Anne Frank’s secret hiding place furnished as if they had just left, before the Nazis stripped everything out. Indeed, that is how you experience The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, totally empty. (The people from Anne Frank House in Amsterdam remarked how strange it was to see the rooms they know so well as empty, now furnished. “But we have the original diary, you have a facsimile!”) Also, it is what the exhibit is wrapped around with – the context surrounding Anne Frank’s experience and the experience of the 6 million Jews, including 1.5 million children exterminated in the Holocaust.

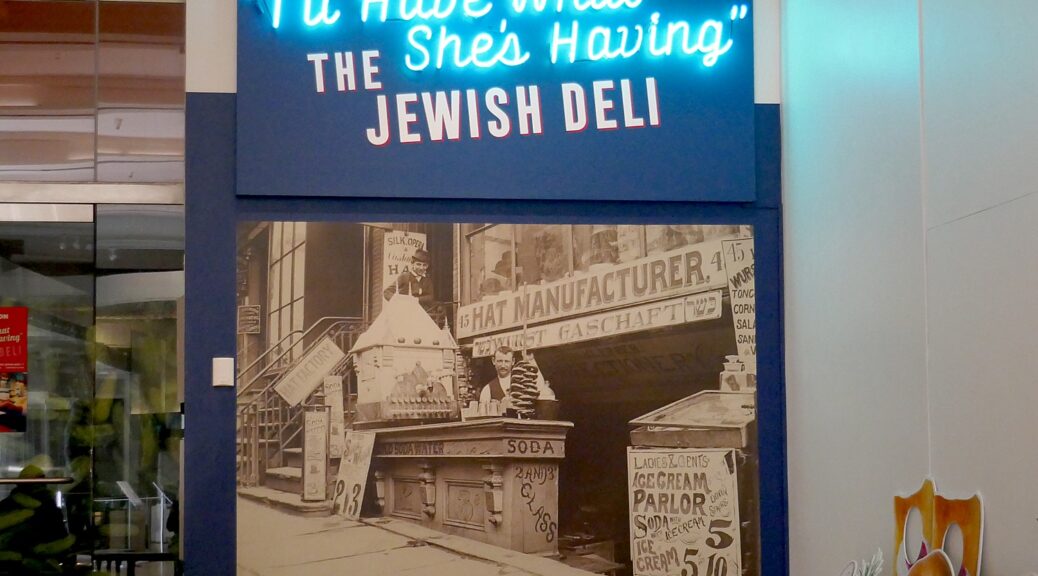

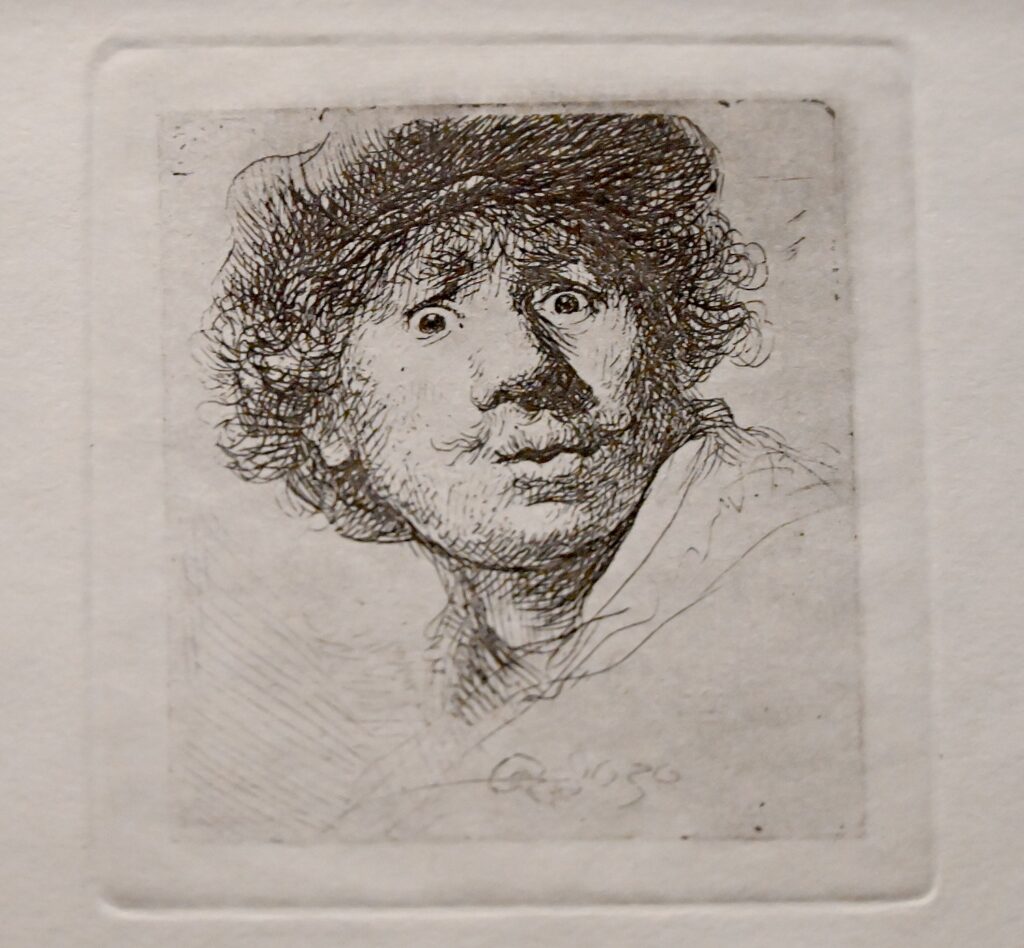

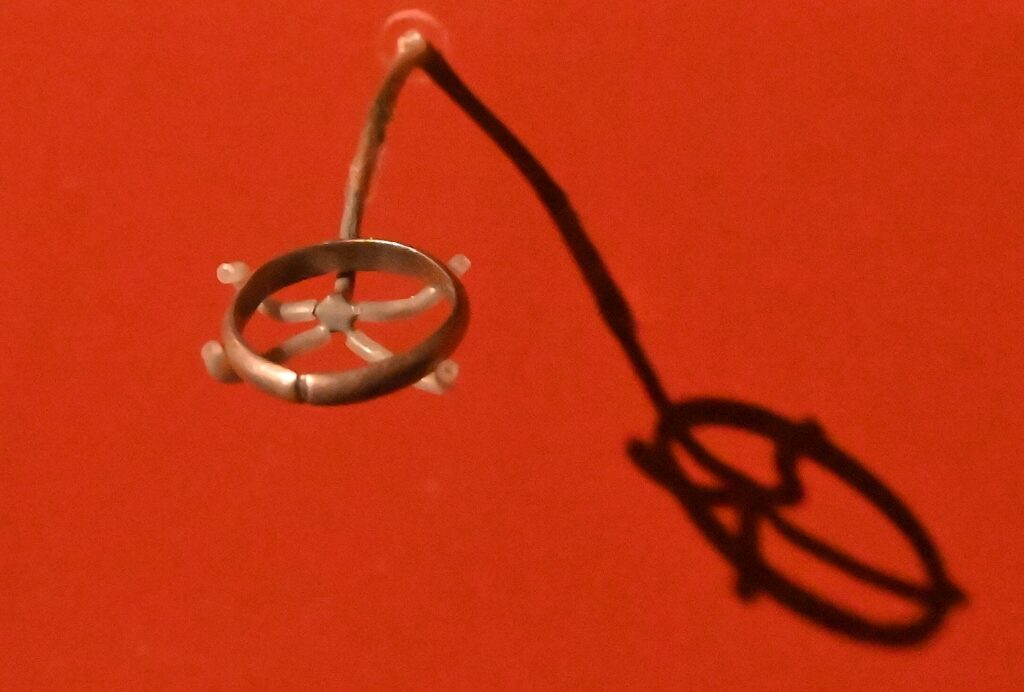

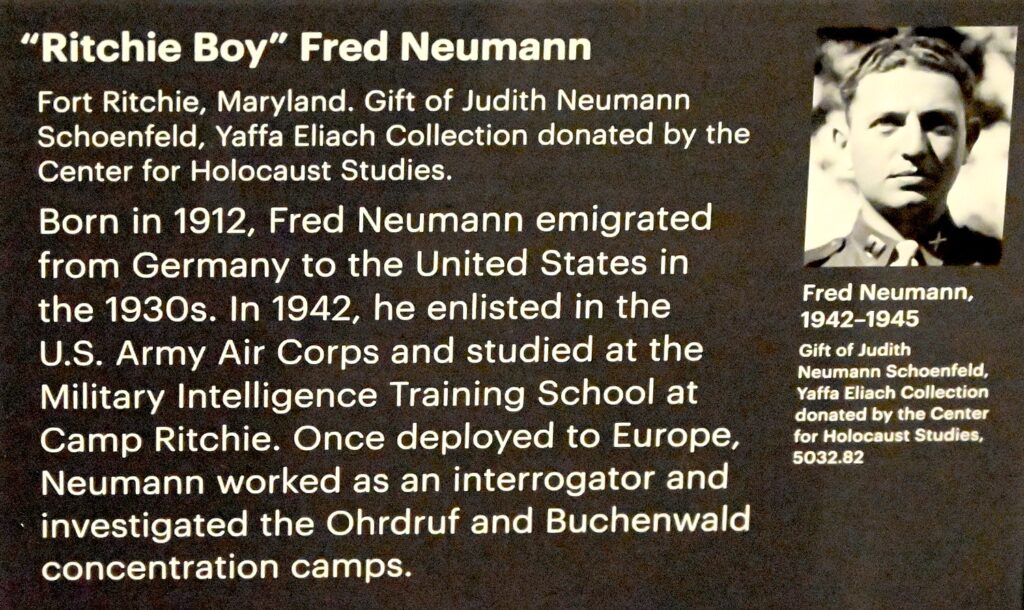

The exhibit features some 100 artifacts – some rarely if ever viewed in public – including an extraordinary exhibit of the family’s personal effects from their comfortable life in Frankfurt where Otto was a banker, before the Nazis and the Holocaust – even their china, a wooden desk from 1796, and Anne’s first photo album (1929-1942). You see family photos and photos of a normal life, a playful child with a fetching smile. There is even a video of a wedding couple leaving their apartment building that happened to capture Anne peering out from a second-story window.

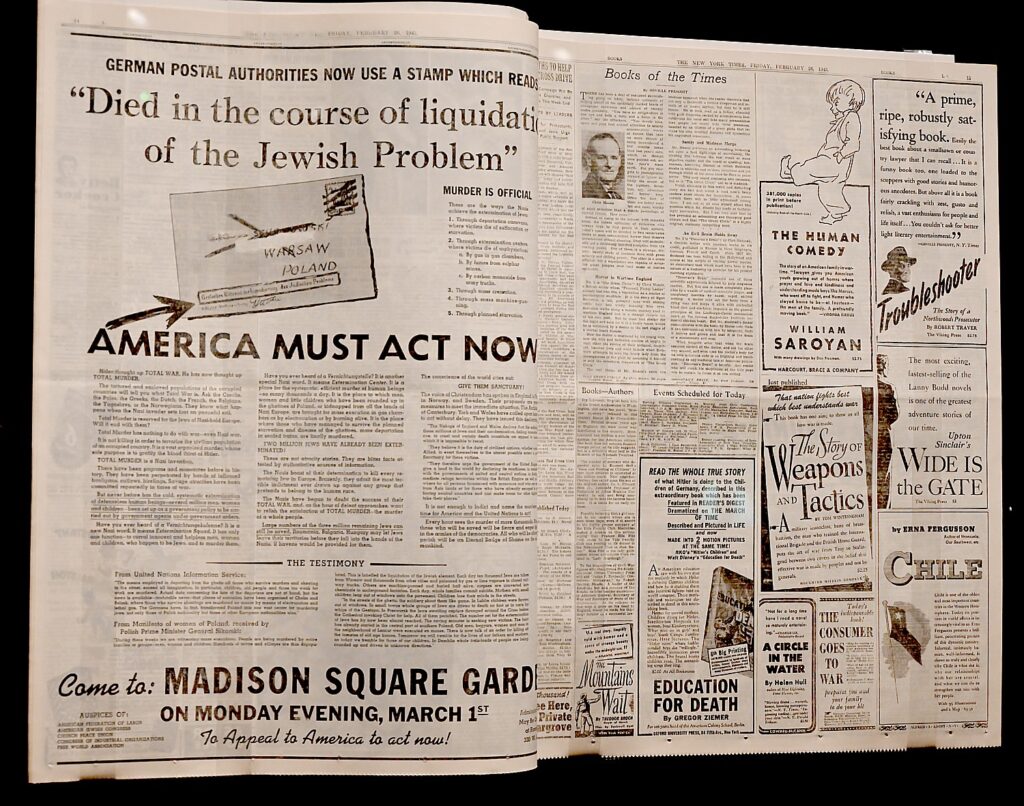

This exhibit wraps Anne Frank’s personal story with context: the rise of Hitler, democratically elected Chancellor, and the Nazi domination of Germany, the invasion of the Netherlands, France and Belgium, and the implementation of the Final Solution – systemic genocide of Jews, known as the Holocaust.

We walk through the bookcase, and are in the hiding place in the Annex. Throughout the exhibit, you have an audio guide that you can activate, but here, in the hiding place, is where what you hear is most affecting – not just the description of the place and what their lives were like for the two years they hid away, but Anne’s own words from her diary.

“When I write, I can shake off my cares, my sorrow… my spirits soar…. But will I ever be able to write something great? Will I ever be able to be a journalist or writer? Oh, I hope so.” And then, “Writing allows me to record everything – thoughts, ideals, fantasies.”

Anne decorated her tiny cramped room with pictures – Hollywood and Royalty, like any 13-year old. But by the time she was 15, her interests shifted and deepened -she favored art and history and more serious things.

We visit all their rooms – you feel you are intruding, actually – even the bathroom, where you hear that at the stroke of 8:30, there could be no running water, flushing toilet, walking around, no noise whatsoever.

The kitchen, where the Pels slept, served as the communal kitchen and living room, and is where they played games at night and celebrated holidays like Yom Kippur and Chanukah.

Anne describes how one moment they are laughing at the comical side of their hiding, the next, feeling frightened. “Fear, tension and despair can be read on our face.”

Then, on a fateful day, the audio guide relates, a man came up the stairs with a revolver and told them to “pack their bags, you have to leave.” They were taken to prison and on to the camps.

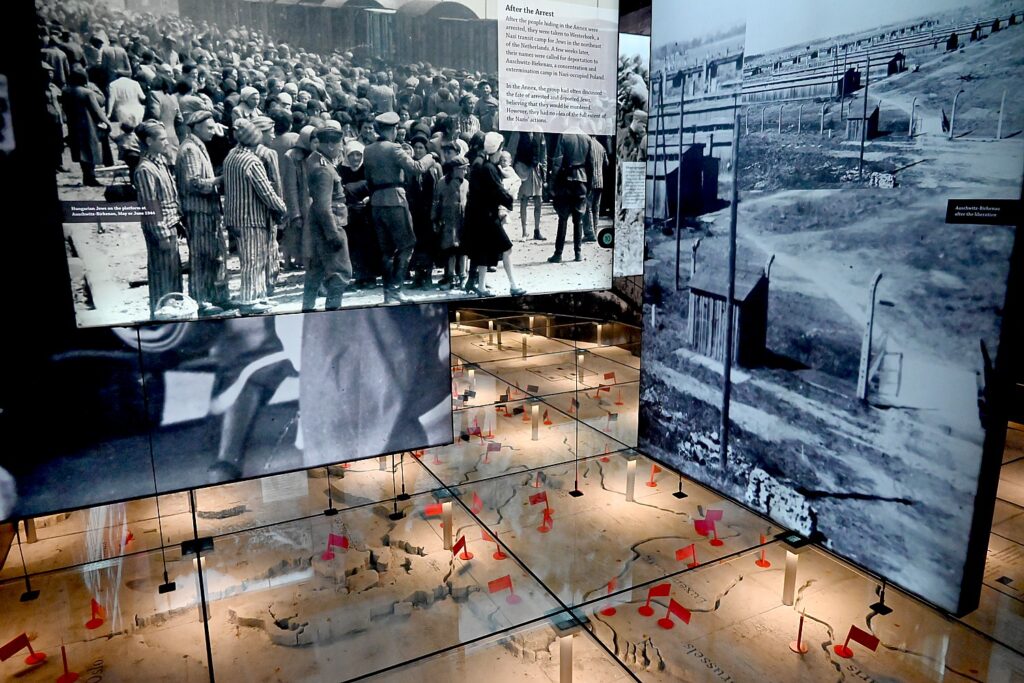

In the next rooms, you see how the Holocaust unfolded – photos of Jews pulled from their homes, crowded into the streets and loaded onto cattle cars, deported to labor, concentration and death camps. You see soldiers shooting masses of Jews in pits dug by the victims themselves.

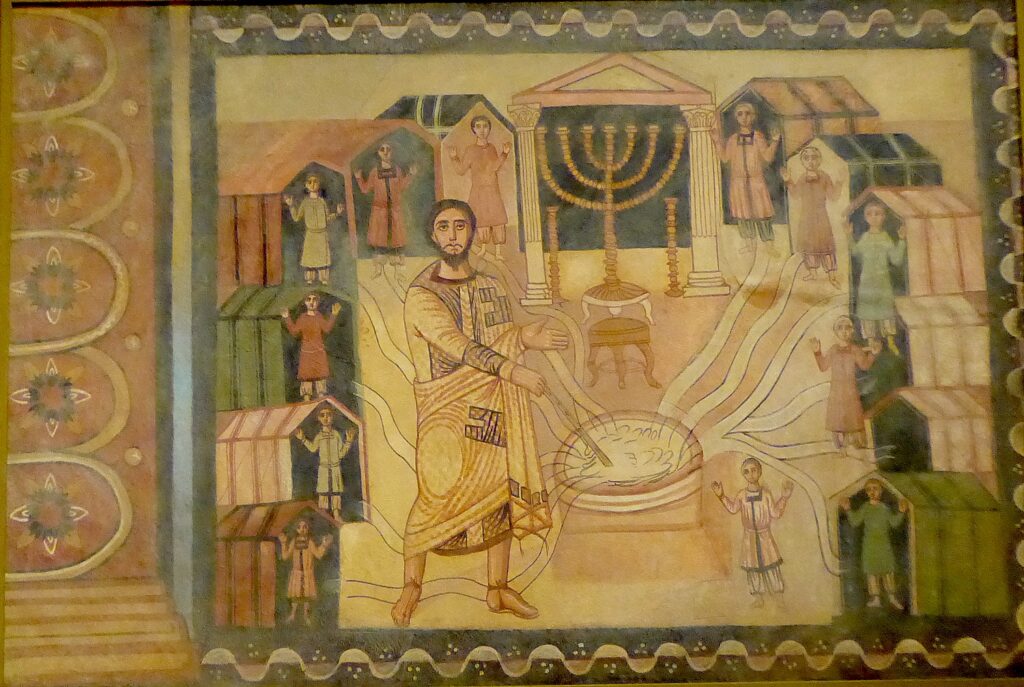

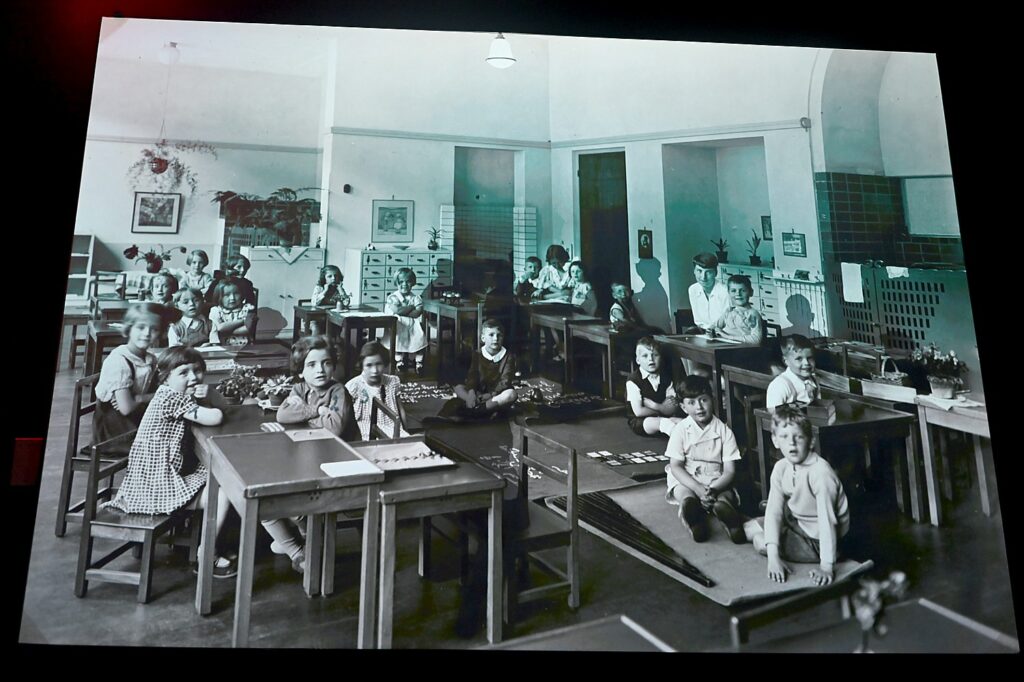

This room has a glass floor over a map of Europe with red flags denoting where the death camps and places of genocide were and hear names recited. As you come to the end, most affecting of all, is a projection of the 1935 photo of Anne Frank in her kindergarten class of 32 students, of whom 15 were Jews, which you saw in the first gallery. As you hear their names ticked off, one by one these adorable, innocent faces are disappeared from the photo and you hear their age when their lives were snuffed out: 12, 13, 14, 15. Only 5 of the 15 survived – by going into hiding or escaping. Anne was 15.

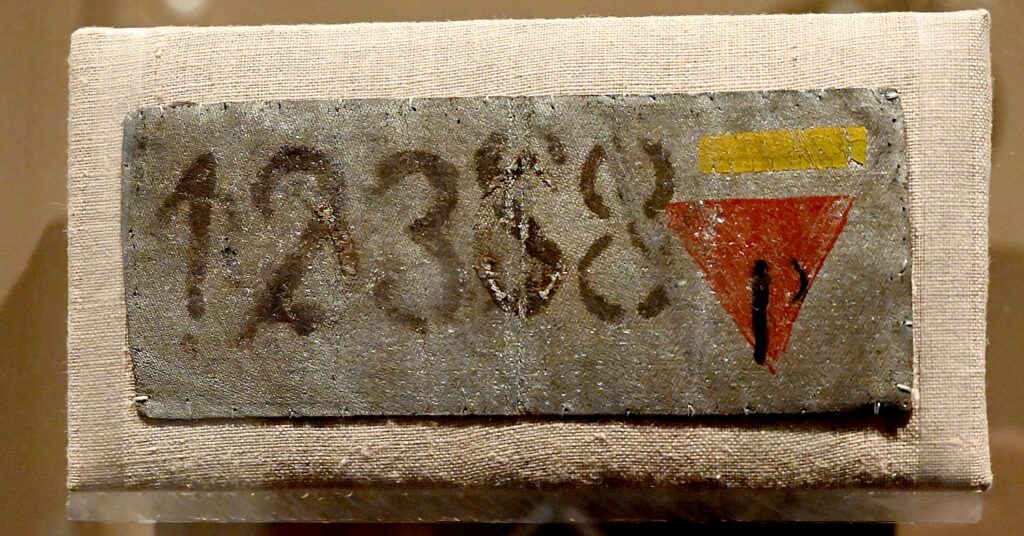

The next part follows Otto’s improbable journey from the camp when it was liberated in January 1945. Otto was the only one to survive of the eight who hid in the Annex, though he had yet to learn the fate of his family. All of his worldly possession fit into a tiny canvas bag the size of a book.

For Otto, it was just 10 months after being arrested that he returned – all of those who helped them in the Annex survived, though two men were arrested and sent to concentration camps but survived.

You actually see a video of Miep Gies, one of the Dutch citizens who hid and protected the Franks in the Annex (she lived to 100 years old), relating how she went into it after the Nazis ransacked it and found Anne’s diary and notebooks, keeping them safe because she knew how important her writing was to her. She re-creates how she reached into her desk and presented Otto with Anne’s volumes.

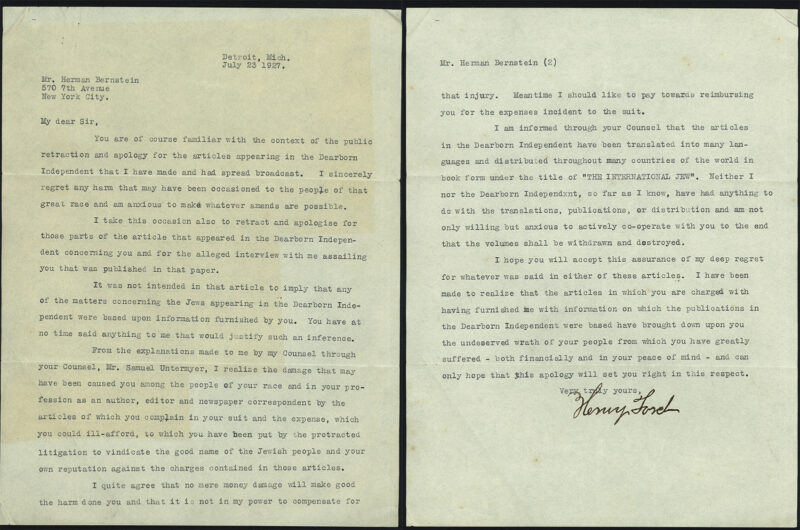

In an interview, Otto related that at first it was difficult for him to read the diary because of his grief, but when he started reading, he couldn’t stop. To honor her wishes of becoming a published writer, he set out to find a publisher – you see his letters and the replies from editors.

“Anne Frank’s diary, ‘Untergetaucht,’ [The Annex] impressed me deeply,” one editor writes back, “a monument to the sufferings of all people in Holland during the war…. If conditions were more nearly normal, I would recommend that we undertake an English translation…”

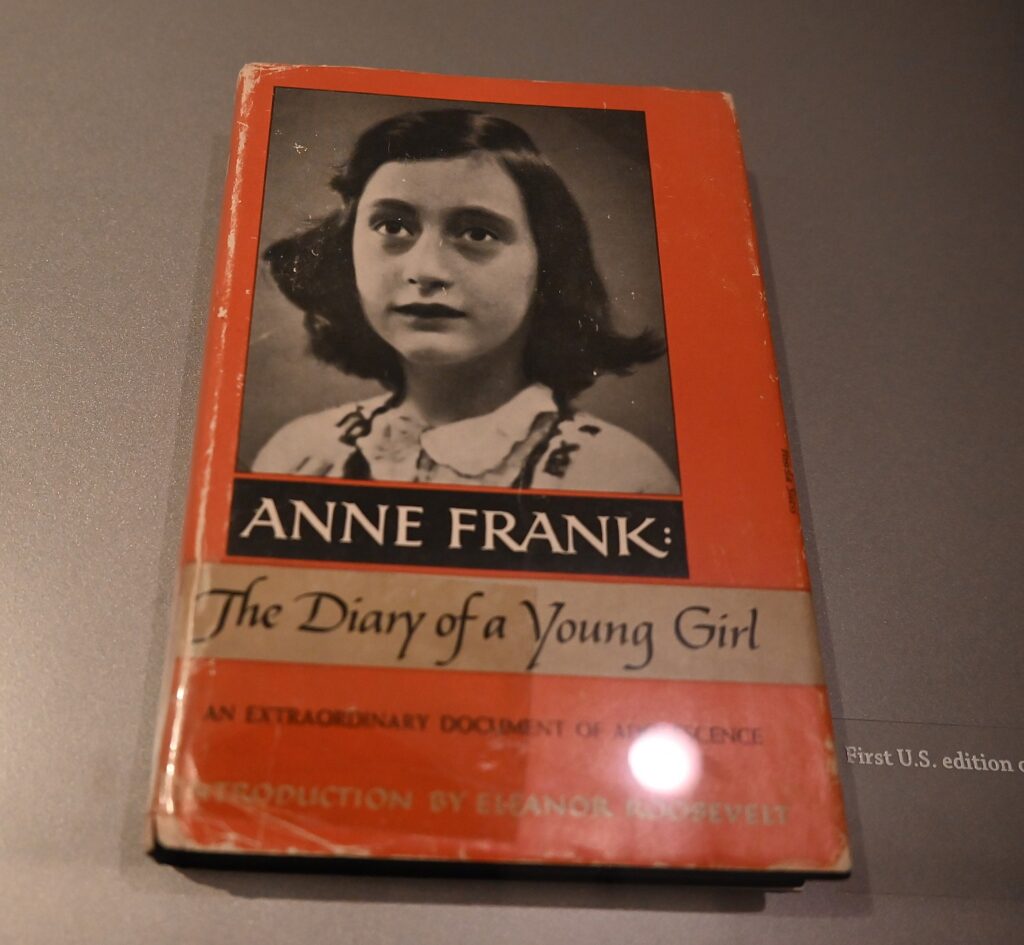

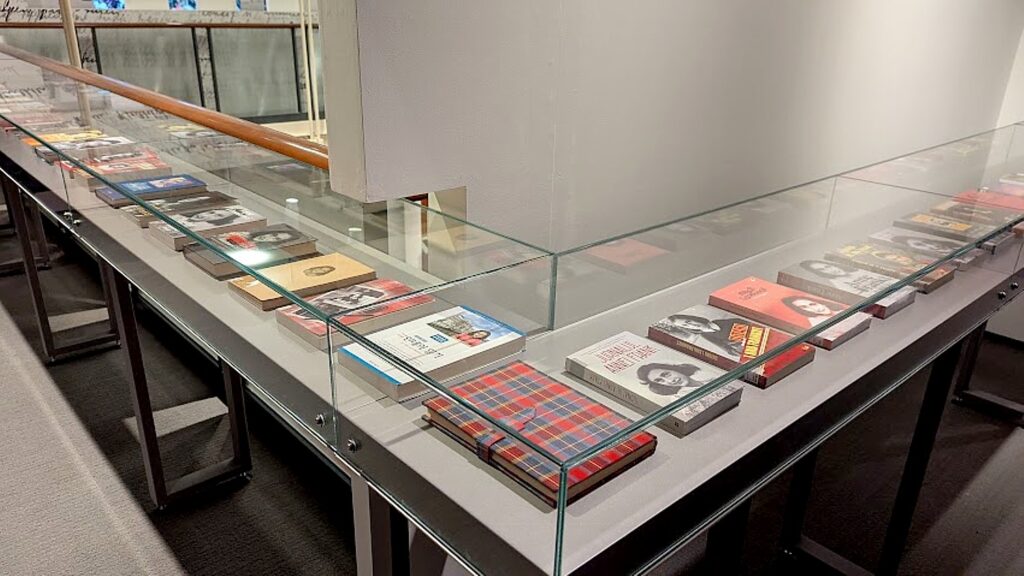

But ultimately Anne’s diary was published in English, “Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl” – you see the first edition which includes a forward by Eleanor Roosevelt – and translated into 70 languages, selling 35 million copies – and made into a play and movie (winning Shelly Winter’s an Oscar for her performance as Auguste van Pels).

The exhibition closes quoting Anne Frank, “I’ll make my voice heard, I’ll go out into the world and work for mankind!”

Otto Frank is quoted saying in 1973, “Anne’s Diary made you think about the cruel persecution of the Jews during the Nazi regime, but I want to stress that even now there is in our world a lot of prejudice leading to discrimination and everyone of us should fight against it in his own circle.”

Michael S. Glickman, CEO of jMUSE, a former director of the center, said, “This institution, one of the great Jewish archives and libraries in the world, will house singularly the most important Jewish exhibition presented in this country. It is such a privilege, honor to be involved in this exhibition that carries the memory, legacy, and future of the Jewish people in such a powerful and poignant way…. As we open, we do so in memory of 6 million Jews and the 1.5 million Jewish children murdered.”

The exhibition is designed for children (ages 10 and older) and adults. All general admission tickets include the exhibition audio guide. Plan to spend two hours.

Individual tickets: Timed entry tickets, Monday through Friday: $21 (17 and under, $16); Sunday and holidays: $27 (17 and under, $22); Flex tickets, Monday through Friday: $34; Sunday and holidays: $48

Family tickets (2 adults + 2 children under 17 years): Timed entry tickets, Monday through Friday: $68 (additional 17 and under ticket, $16); Sunday and holidays: $90 (additional 17 and under ticket, $22) Flex tickets, Monday through Friday: $95 (additional 17 and under ticket, $18); Sunday and holidays: $135 (additional 17 and under ticket, $25).

Hours: Sunday through Thursday: 9:30 am-7:30 pm, Friday: 9:30 am-3:30 pm; closed Saturday.

Educational visits to the exhibition, as well as Individual and Family ticket purchases, can be scheduled by visiting AnneFrankExhibit.org.

Anne Frank The Exhibition is a limited engagement, scheduled to close on April 30, 2025. For a list of upcoming programs, visit https://www.cjh.org/.

Genealogy, Holocaust Records at the Center

The Center for Jewish History also has Geneology Research Center, with genealogists on hand who can help you trace your family’s history, has formed a new-multiyear partnership with Ancestry® to open the Ancestry Research & Reflection Room, a new space and initiative to collect, preserve and share family histories of Jewish communities worldwide.

Ancestry®, which is committed to preserving the memories of Holocaust victims and survivors and ensuring that these records are freely accessible to future generations, together with the Arolsen Archives, one of the world’s leading institutions for Holocaust documentation, expanded its Holocaust-related resources by adding 7.5 million more documents to its resources, including Germany, Incarceration Records, 1933–1945.

These records can be searched for free at a newly opened Ancestry Research & Reflection Room at the center – a new space and initiative to collect, preserve and share the family histories of Jewish communities worldwide. It is opening to the public on January 27, coinciding with the opening of the Anne Frank exhibition, International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

Center for Jewish History 15 West 16th Street, New York, 212.294.8301, cjh.org, info@cjh.org.

__________________

© 2025 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Bluesky: @newsphotosfeatures.bsky.social X: @TravelFeatures Threads: @news_and_photo_features ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures