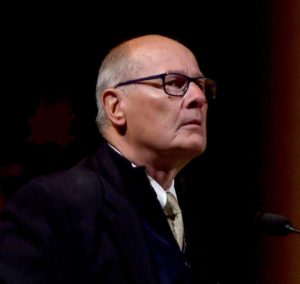

By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

Travel expert Pauline Frommer, of the Frommer Guides and radio show, says that 2017 is probably the best year for Americans to travel abroad because of a surging dollar, competitive pressure on international airline fares, and an international climate where destinations are thrilled to have foreign visitors.

But she began her presentation to the 2017 New York Times Travel Show counseling travelers to be skeptical of technology that is transforming so much of how people travel and even where they travel – how online search engines can force you into purchasing more expensive hotels and airlines based on the profile that previous searches create, and, as a corollary, the intrusion into privacy.

“Often the answers you are going to get through an online search aren’t necessarily the answers you want.” This is especially true because of the way the search engines keep track – through cookies, for example – and will provide listings that seem to conform to previous searches.” The cookies might be in your computer after you did a search for a hotel or a business trip where the boss pays, so you book a $400/night hotel. “So when you try to find a hotel for a family holiday, in your search, all the expensive hotels come up first. It’s more difficult to find the least expensive.”

This is true for flight searches on popular sites (like expedia.com), where if you log off, then go back, you might find that the flight is $200 more. The way around it? You have to either clear your browser of cookies, or go online again on a different computer, or “even go to Starbucks and use their WiFi.”

Based on research that Frommer commissioned from a freelancer, Frommer recommends a couple of websites for airline searches:

Momondo.com (which doesn’t use cookies, so when you return, the price is same but you have to reenter information); and Skyscanner.net (which does use cookies)

She also counsels that the cheapest days of the week to book are Saturday, Tuesday & Wednesday flights.

And based on a study of 26 million airline transactions by the Airline Reporting Corporation, which acts as middleman between airlines and travel agencies (online and storefront), there are trends in fares (she warns won’t always be true and likely not for traveling on Christmas or SuperBowl weekend). Nonetheless, to get the best fares, she advises:

Book on a weekend, 19% savings

Book 57 days before travel for domestic tickets,10% savings

Book 176 days before travel to Europe, 11% savings

Book 77 days before travel to the Caribbean 5% savings

Book 160 days before travel to Asia/Pacific 13% savings

Book 144 days before travel to the Mideast, Africa, 24% savings

Book 90 days before travel to Central/South America, 10% savings

Frommer (as well as travel expert Peter Greenberg) warn buyers to beware of the new category of “basic economy fares” which American Airlines recently introduced, following on heels of United and Delta. Averaging $25 less than regular economy, the airlines have tended to offer them in markets where carriers have competition from low-cost carriers like Frontier and Spirit.

“But these are really, really ugly. You will never get to choose your seat, which means you are likely to wind up in a middle seat. This is a problem if you are travel with children – if there is a plane crash, how could you leave the plane if your kids are in different seats. I don’t think will be brought up soon with current administration.” On American and United, the austerity goes beyond (and is even parodied by comedians): you don’t get to use the overhead bin, you can only bring on board the plane what you can slip under your seat; if you need to check luggage, it costs $25. Another disadvantage: you don’t get any loyalty points when you buy a basic economy seat (though loyalty doesn’t mean much of anything, anymore, she adds).

“Rethink loyalty. Loyalty has been devalued by the airlines now. In the last year, you would get points for how many miles you traveled; now it’s for how much money paid, that is multiplied by how high you are in their system. If you are a big-time business traveler, your money is multiplied by 5; if you only travel only twice a year, it is only multiplied by 2 – not greatest system. It will cause major fights at the gate.” American, she says, is soon going to use its new Loyalty standard to determine where you get on a list to upgrade (it used to be, as an elite member, first-come, first serve, now the airline will look how much money you spent to get elite membership).

The only way to make the points game work in this climate, she advises, is to use credit cards.

Good news for travelers: airfares in the US have stayed stable, and airfares abroad are dropping dramatically because of new players like Norwegian Airlines (offering $499 fare each way to London), WOW airlines, XL Airlines (operating to Paris, www.xl.com/us/, which used to only concentrate on French travelers, but now Americans, too); Thomas Cook Airlines, Eurowings, AirAsia, Emirates, and soon, JetBlue, adding, “Any airline flying into the United States has to adhere to our gate standards.”

Emirates Airlines, which has been offering low fares, is not new but going to a lot more places in Europe for a lot less money. “Now Milan is the cheapest gateway in Europe because of Emirates.” And the international scene may get a new competitor, as JetBlue is looking to starting to fly to Europe.

Also, AirAsia has started flying to Asia, pushing fares down 25% from last year.

How do you find great ways to sightsee besides using Frommer guide? All around the world, you can find local walking tours led by starving graduate students. “These are people who go to places like Venice, Rome, New York, Chicago to work on dissertations and to make a little extra money, often lead walking tours. They know they have to be really entertaining or they won’t get a tip (which is all they make). The best walking tour in Rome, Through Eternity, is led by a woman writing her dissertation on Michelangelo, who had been studying letters his assistants on scaffolding had been writing the Pope. From those, she learned that Michelangelo, who was from Florence, believed Rome’s water was poisoned and because of that, did not bathe for the 10 years he was in Rome. That’s what his assistants were writing about. This woman really knew and was passionate about what she was speaking about.” Such tours can also be a refreshing change from tour guides who, because of limitations on purchasing licenses, have been at it for decades, and “sometimes are so bored telling about Hadrian’s Gate for the 10,000th time.”

Atypical tour companies include:

G Adventures

Djoser

Intrepid Travel

Explore!

Context Travel

Road Scholar

G Adventures, Djoser, Intrepid Travel all are designed around small groups, never more than 12 people, use locally owned guest houses, local transportation to keep green [and provide a closer, more authentic experience], provide a lot of free time to explore on your own, and tend to be much cheaper than the competition. G Adventures is based in Canada, Djoser in Holland, and Intrepid is an Australian company so you are not just traveling with other Americans, but people from all over the world [which is also a special experience].

“I took an Intrepid family tour with my kids in Morocco. It was the most wonderful tour because of our group. We had a German family, 2 British families and a family who lived four blocks away from us in Manhattan. Explore!, an interesting British company, does hardcore tours of places that are otherwise difficult to get to on your own – the Stans, deep Africa, deep south Africa. Context Travel hires erudite guides – it is the most expensive on list, but they run really smart learning vacations to major cities. It started in Italy, now everywhere. Road Scholar (used to be Elderhostel) is for seniors, offering smart tours, hub and spoke so you stay in one place and take day trips; tours are often led by professors, educators.”

Under the category “Solo travel with a safety net,” Frommer cites Women Welcome Women (a UK-based international membership network started by a woman who was jealous of son being able to do exchange, http://www.womenwelcomewomen.uk/article/home.aspx; which is not a travel agency or travel company, but basically network women traveling to other cities).

Greeter Tours are free tours run by local who love showing their home town to people from around the world. (in NYC, Chicago, Houston, Paris, Lyon, Bangkok, Delhi, Cordoba, Grenada, Sydney, etc. (GlobalGreeetersNetwork.info)

Accommodations. There’s been a sea-change in accommodations – AirBnB now has more beds in its inventory than all the major hotel chains combined. “Last year, [hoteliers] were saying AirBnB wasn’t affecting prices because a different person uses AirBnB. But this year, they are saying it is affecting prices. It used to be hotel chains would know they could raise prices sky high for a major holiday; now they no longer have that kind of security [control].”

The best search sites for accommodations, she says, are HotelsCombined.com (#1 for prices 92% of the time, according to a study, but Hotelscombined doesn’t actually sell from inventory, it just Googles), followed by Trivago (which is owned by Expedia; expedia gets inventory from the major chains).

In terms of OTAs (online travel agents), booking.com wins (not just the big hotel chains), followed by Asia specialist Agoda.com (best prices for Asia).

The best Booking Blind sites are: Priceline.com, hotwire.com, and biddingtraveler.com.

For lodging rentals, she recommends:

AirBnB.com

Homeaway.com (owns Rentals.com, owned by Expedia, massive corporation)

Zonder.com

FlipKey.com

VRBO.com

Sea Changes in Cruising: The cruise industry is seeing a sea change in technology. Frommer is skeptical about where technology is leading, particularly the juncture of privacy and marketing.

Carnival Cruises, for example, is very excited about a new medallion that replaces a key card, credit card, and knows if you are scheduled for a yoga class or a show or have a restaurant reservation.

“Medallion or Horcrux? They hook you up to an app. They know where every member of your party is, open your door, order a drink, and will sell you things. I find this disturbing – from the point of view of the lack of privacy –a large corporation is going to know everywhere you are. They will be able to up-sell you. You may be glancing at a list of shore excursions and somebody will appear at your side to tell you why you should take a shore excursion.”

But one good trend in cruising, she says, are the lines that have responded to complaints about getting into a port at 9 am and leaving at 2 pm. Some are changing itineraries to allow more time in port, and some make it a focus. Azamara Club Cruises (which pioneered overnight stays, even 2-3 nights in a port so you can really get to know a city, but the trade-off is fewer sea days to relax) and other lines where they give you more time in port, like Oceania, Celebrity Cruises, Costa, MSC, and Holland America, so you can experience nightlife in a place and you don’t have to rush back to ship).

Cruiselines also are introducing new ports to their itineraries such as in Ireland, Australia, Asia, Scandinavia).

Frommer has a bugaboo about how much shore excursions cost: “They scare guests to take them when they don’t need to. They say if you don’t, the ship can leave without you. I say, get a watch. In most cases, you can wander off the ship and see as much as the shore excursion.

But, you can purchase less expensive port excursions than the ones offered by the cruiseline through such agencies as CruisingExcursions.com, ShoreTrips.com, Viator. CruisingExcursions.com and ShoreTrips.com offer 12-person vans and usually charge 2/3 of cruise ship costs. Viator is more of a marketplace for city tours will give you guarantee that if you miss the boat they will pay to get you to next stop.

There are tremendous differences in cruiselines – aesthetics, what the experience is like. “When you take a cruise, the ship is your vacation, so get the best ship for you. Use a travel agent. This is one area where you are foolish not to use travel agents – those who specialize in cruises, get special discounts they can pass along, complimentary upgrades, shipboard credits, bottle of wine. They know their boats [and typically have toured the ship and have worked with the line]. Not all travel agents are equal. Ask questions. Make sure the travel agent represents all lines or, at least, the ones you are interested in. They can suggest the best cabin for the price you are willing to pay.

River Cruising has become extraordinarily popular, largely due to the success of Viking River Cruises. “For centuries, the rivers of Europe, Asia, America were the arteries that people used to get place to place, so you are in the middle of everything. You step off the boat and in front of you is the cathedral, the historic square.” (Frommers has a guidebook just on river cruising.)

But not all river cruises are alike, she notes.

In the category of Over the Top, most luxurious: Uniworld, Tauck, Scenic. “Uniworld has a designer that Marie Antoinette would approve – crystal, silk wall paper; it’s over the top extravagance. Tauck is as luxurious but a little more contemporary in décor, well known for shore excursions. The dirty little secret of river cruises is that all the river cruises except Tauck and Gate 1 share the same guides on shore. Scenic gives all its guests headphones, so can hear commentary about what you are passing on shore; it is an Australian company so you are traveling mostly with Australians and blasts Olivia Newton-John at night; it offers fun trips (and also owns a budget river cruisline, Emerald Waterways).

Luxurious: AmaWaterways, Viking River Cruises, Avalon Waterways. Avalon and Ama are trying to attract younger crowd with more active experiences – kayaking on river; Ama carries bikes on board.

Budget – Emerald Waterways, Grand Circle, Croisie Europe. “Croisie Europe is the second biggest river cruise company in the world after Viking, but you probably never heard of it because the line only marketed to Europeans until recently – so in Europe, you are surrounded by Europeans. Croisie tends to have very reasonable prices, but some Americans aren’t comfortable because of a language barrier. “Grand Circle, in contrast, only markets to Americans so you will be on ship with Americans, have burgers at every meal if you want, but in their defense, they do a lot on the educational side, bringing on educators, so the cruises are more erudite, but cheaper than the others.”

Family friendly – AmaWaterways has partnered with Disney to do tours for families. “These are wildly popular and very well done (not surprising, Disney). There are no characters onboard, but they have activities to keep kids busy on land and river. It’s great for multigenerational.” Tauck is another with family-friendly tours.

Best rivers (for first timers): Danube (variety – castle, spas, vineyards, interesting trip), Mississippi (variety, start or end in New Orleans, plantations, Civil War sites, Mark Twain sites); Mekong (because you go to many places you couldn’t otherwise get to except by river cruise).

Where to Go

The US Dollar is strong pretty much everywhere, “whooping every other currency.”

Brexit tanked the British pound

Euro that cost $1.45 in 2012 costs $1.05 in 2017.

Japanese yen lost 1/3 of value against the dollar from 2012

“It’s never been a better time for Americans to travel abroad (at least from a strong-dollar point of view).

As for where to go, Frommer (and Peter Greenberg as well), also tell Americans not to be discouraged by terror attacks in places like Paris, which has lost 30% of its tourism, a vital economic component. “In certain rooms in the Louvre, I was alone; I didn’t make advanced reservations at restaurants, some of most coveted in Europe; the hotel room, everything was cheaper,” Frommer, who visited Paris in June, says., “And Parisians are happy to see Americans. There’s never been a better time.”

But she points out that a lot of the discomfort for Americans, who see headlines and have little comprehension of geography, is perception:

“What do the UAE, Bahamas, France, New Zealand, United Kingdom have in common? They each issued travel warnings against coming to the United States because of gun violence. We are New Yorkers. We know what it is to bounce back [after a catastrophic event].”

But if you are looking for a city like Paris but has bagels? Montreal is celebrating its 300th anniversary this year. The home city of Cirque d Soleil will be the scene of the craziest, most surreal celebrations – 40 foot tall marionettes marching through streets, 3D projections on the river; you can download a free app of the historic district and as you go through, suddenly there is a Sound & Light show.

Haida Gwaii (formerly known as the Queen Charlotte Islands; the people changed back the name to the original First Nations name) “has everything that Alaska has – fishing, wilderness areas, First Nation’s culture but without the crowds and 30% cheaper. I highly recommend visiting before it is better known.”

Indonesia, the largest Muslim nation in the world. “Open the doors. Go there but not necessarily Bali – that is over-loved.” She recommends Sula Wessy – an island of incredible culture, architecture, bright green rice paddies, the smallest monkeys on planet, and fascinating cultural rituals. In

Bali, outsiders can go to weddings and funerals, where welcome; in Sula Wessey, funerals are so elaborate that when people die, they are mummified similar to Egyptians, and left in the house; the mummy lives with the family for years because it takes that long to raise money for the funeral. They have elaborate processions, feasts, dances, and water buffalo sacrifices, then finally the body is buried in rock caves. It is fascinating to visit and less touristic than Bali.

Northern Lights. This is the year to see the Northern Lights, a phenomenon caused by storms on the sun that shoot particles into the Earth’s atmosphere. It goes in a 10-year cycle and 2017 is the last year of the cycle. It will be spectacular this year and crumby for the next. There are inland places in Norway, next to Arctic Circle, where there are no worries of fog from the sea obscuring as well as dog sledding.

Pantanal, the largest inland wetland in the world – twice the size of Iceland, is straddles Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay (?). A decade ago, you couldn’t go in, because it was too difficult, but now river boats go in and for nature lovers it is spectacular because all the foliage is low to the ground so you can see more easily than Amazon – 500 species of birds, jaguars, tapirs, giant otters, fascinating wilderness. It is becoming more popular, so go now.

Nashville – hot – wonderful city – 120th anniversary of Ryman, 50th of Country Music Hall of Fame – every kind of music – get off the plane, live musicians. Foodie scene. Parthenon-replica [Nashville considered itself the Athens of the South], – which sounds silly until you visit – it is the symbol for the city which has many universities, a major medical center, a whip smart population. You will meet great people.

Bermuda – will be home to the America’s Cup this year, undergone millions of dollars of infrastructure rejiggering. Martin Samuelson opening restaurant, great chefs opening. The Hamilton Princess has undergone a multi-million renovation. “More than fun in sun, Bermuda has interesting culture (British, high tea, Bermuda shorts without irony) –a really interesting place, historic sites.”

She adds as a “bonus place” to her list: Cuba. “President Trump has said he will shut the door there and he can with sign of pen. It was opened by President Obama by executive order so can be closed down just as quickly. But Cubans are smart, when Trump was elected, they fast-tracked port rights to Carnival and 5 other major lines, fast tracked hotel building permits to Marriott and Hyatt and are trying to get Corporate America on their side so Trump can’t undo relations. But go to Cuba while you can and before the changes that would inevitably come.

Connect with Pauline Frommer at Frommers.com, @frommers, on Facebook Frommers.

See also:

NYT Travel Show: Greenberg Tells Intrepid Travelers to Exploit ‘Brave New World of Travel’

____________________

© 2017 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures