By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

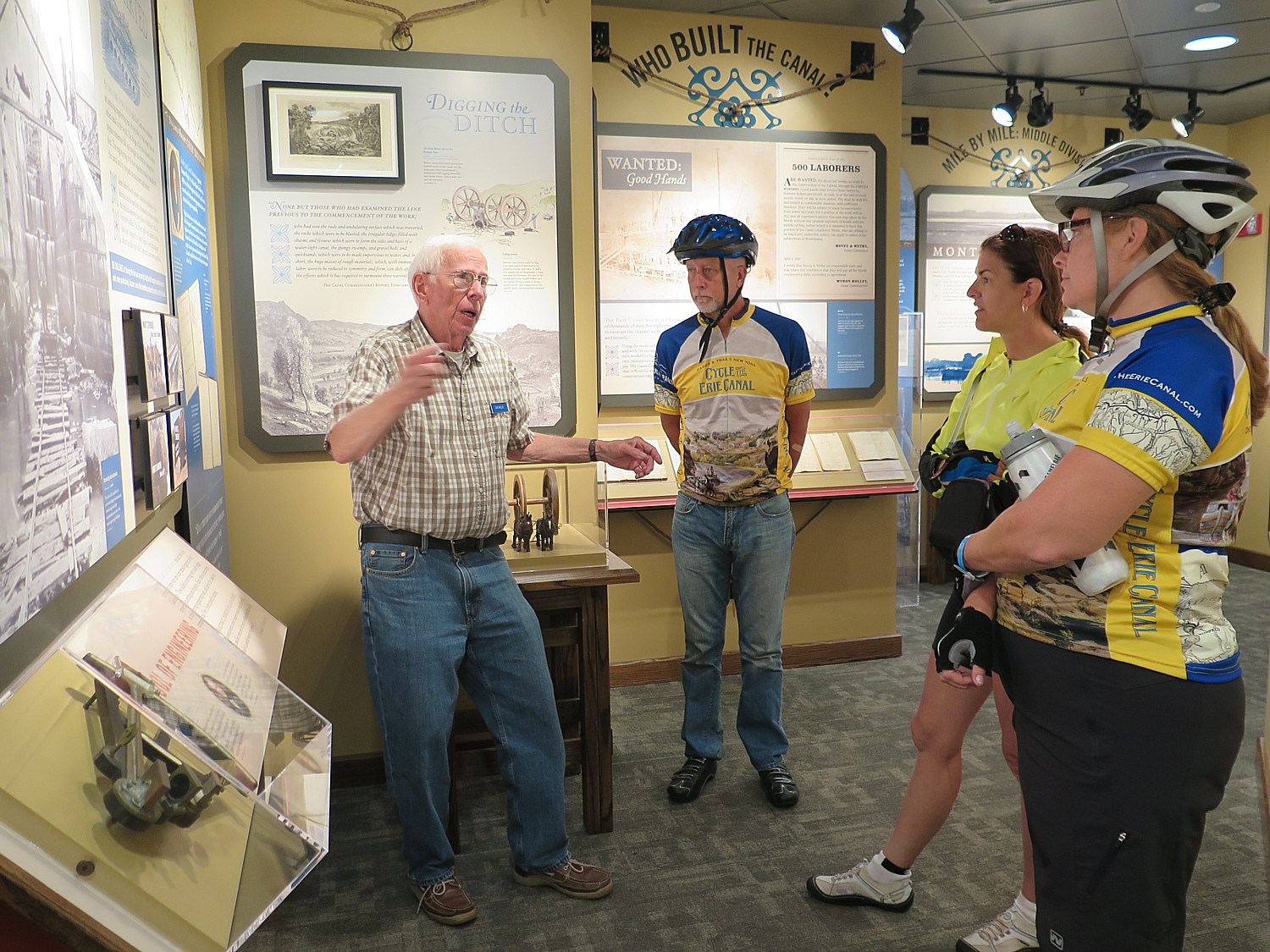

A highlight on Day 7 of Parks & Trails NY’s annual 8-day, 400-mile Cycle the Erie biketour from Buffalo to Albany is Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site. It looks fairly innocuous at first, a farm house along the canal, but here is the only place where you can see all three alignments of the Erie Canal – the 1825 “Clinton’s Ditch”, the 1836 expanded canal and the modern, 1918 “Barge Canal.” The house, now a visitor center, contains a fascinating exhibit and is adjacent to outlines of Fort Hunter, an 18th century fort and trading post, remarkably only discovered after Hurricane Irene in 2011.

The historic flooding caused the Schoharie Creek to breach its banks and destroyed the site’s parking lot. After the flood water receded, a number of stone walls and numerous artifacts associated with Fort Hunter emerged. Excavations revealed flat stone foundations upon which a fort wall and 24-foot square blockhouse would have been constructed.

After the archaeological work was completed, these original fort foundations were preserved by reburying them. Their exact locations are now represented on the surface with modern stone pavers. Artifacts recovered during excavation included a mix of domestic and military objects that represent the site’s Mohawk and British occupants. Dates associated with the artifacts suggest that the blockhouse saw greatest use from the 1740s to 1760.

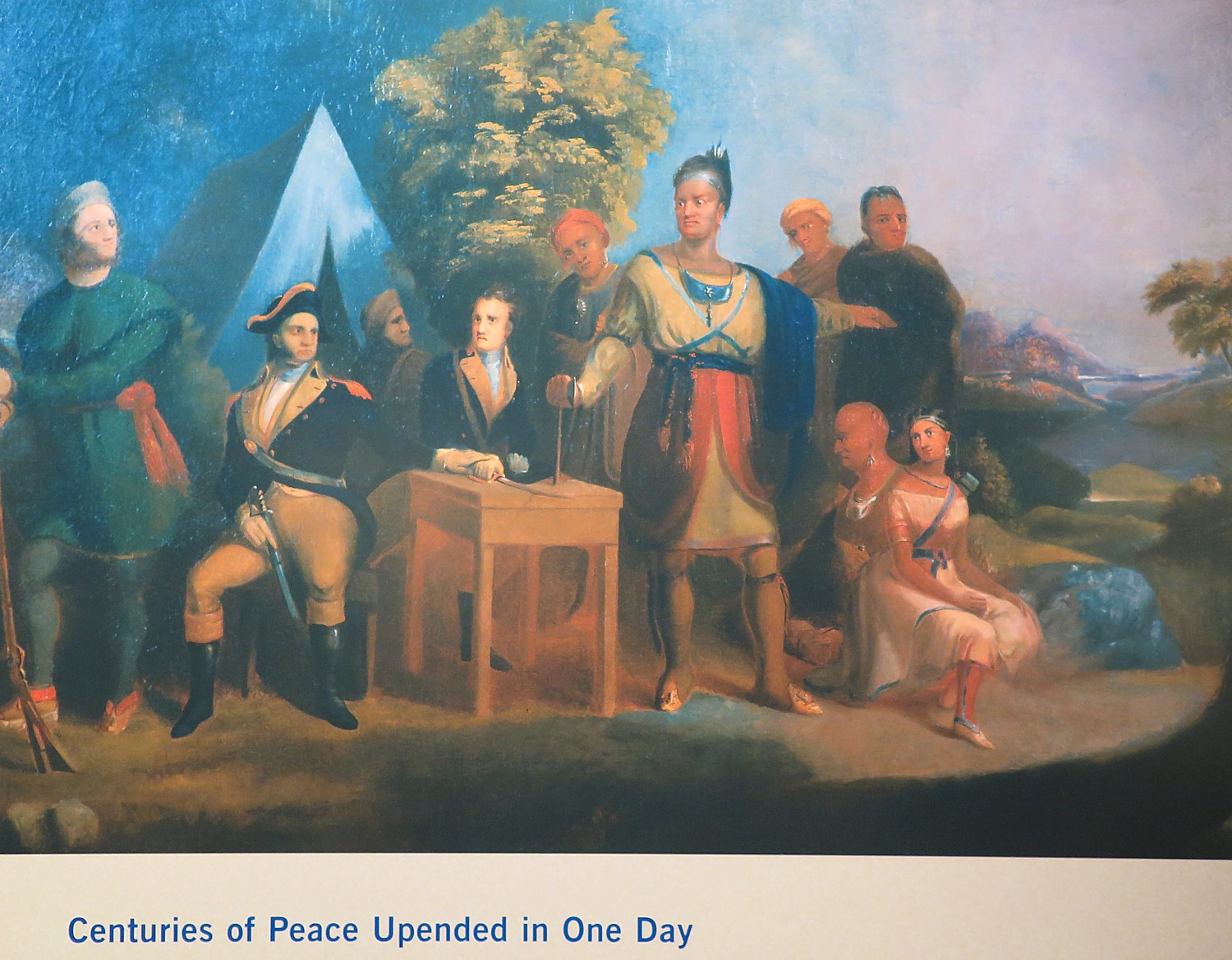

Though you don’t really see anything of Fort Hunter, it points to how significant this area was in colonial times: Schoharie was a place of key interactions between Europeans and Indians, setting up a later clash of cultures.

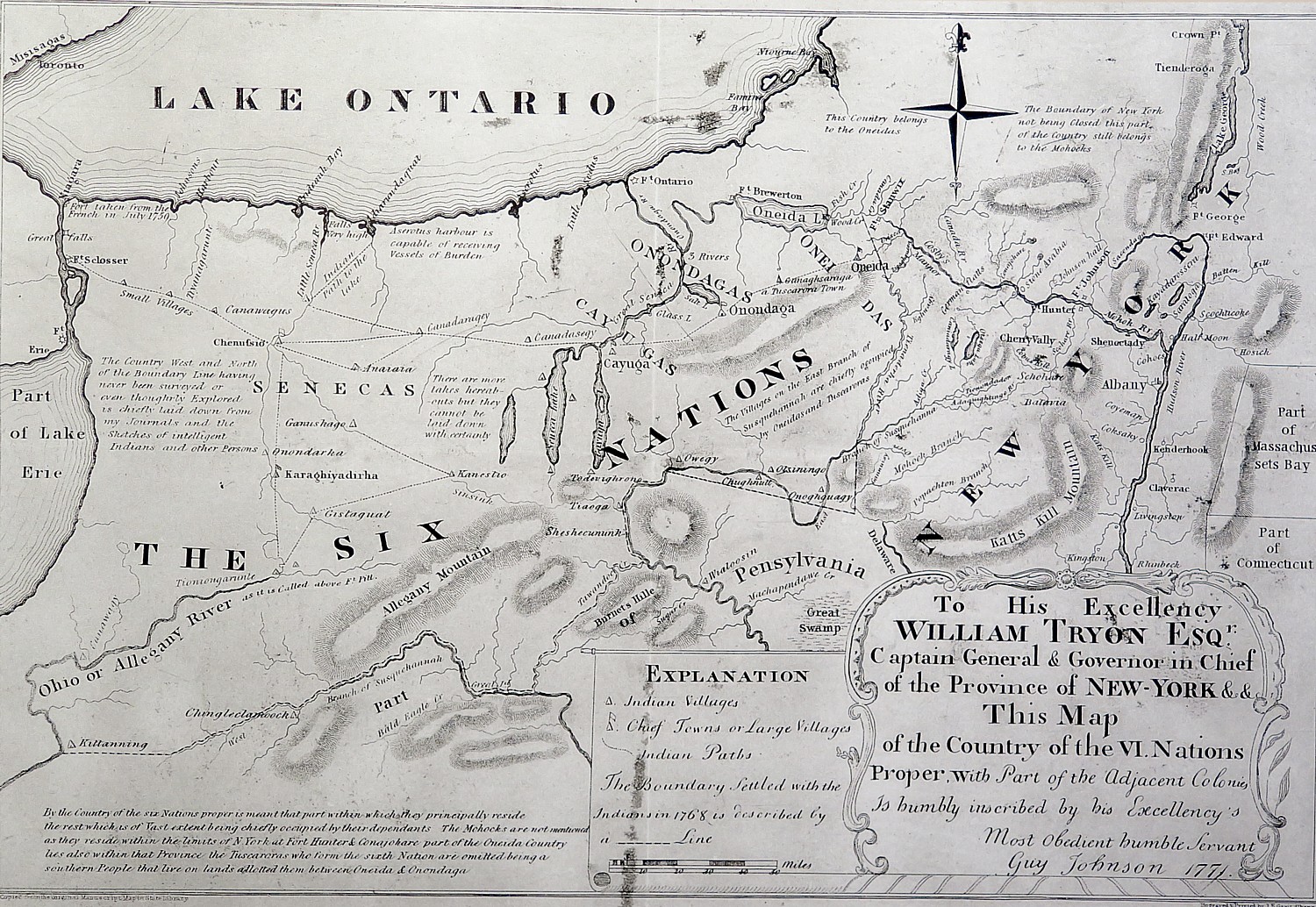

During the 1600s, the British and French competed for control here. In the 1690s, the British forged an alliance with the Iroquois to establish a permanent structure – a fort/trading post – in order to solidify their standing.

The Indians at the time of the Revolutionary War were settled on farms and in towns. They employed European style farming techniques, lived in houses, and the gender roles started to shift away from the matriarchal society to male-dominated, copying the Europeans.

By the time of the Revolutionary War, there might have been about 10,000 Indians living in the area.

“They didn’t have a concept of property ownership. They were outnumbered early on” largely because of the diseases the Europeans brought that wiped out large numbers of the population, and over-trapping which pushed many further west.

“They were very good at diplomacy – well organized – and controlled access to the waterways. They played the European powers,” David Brooks, Education Coordinator says.

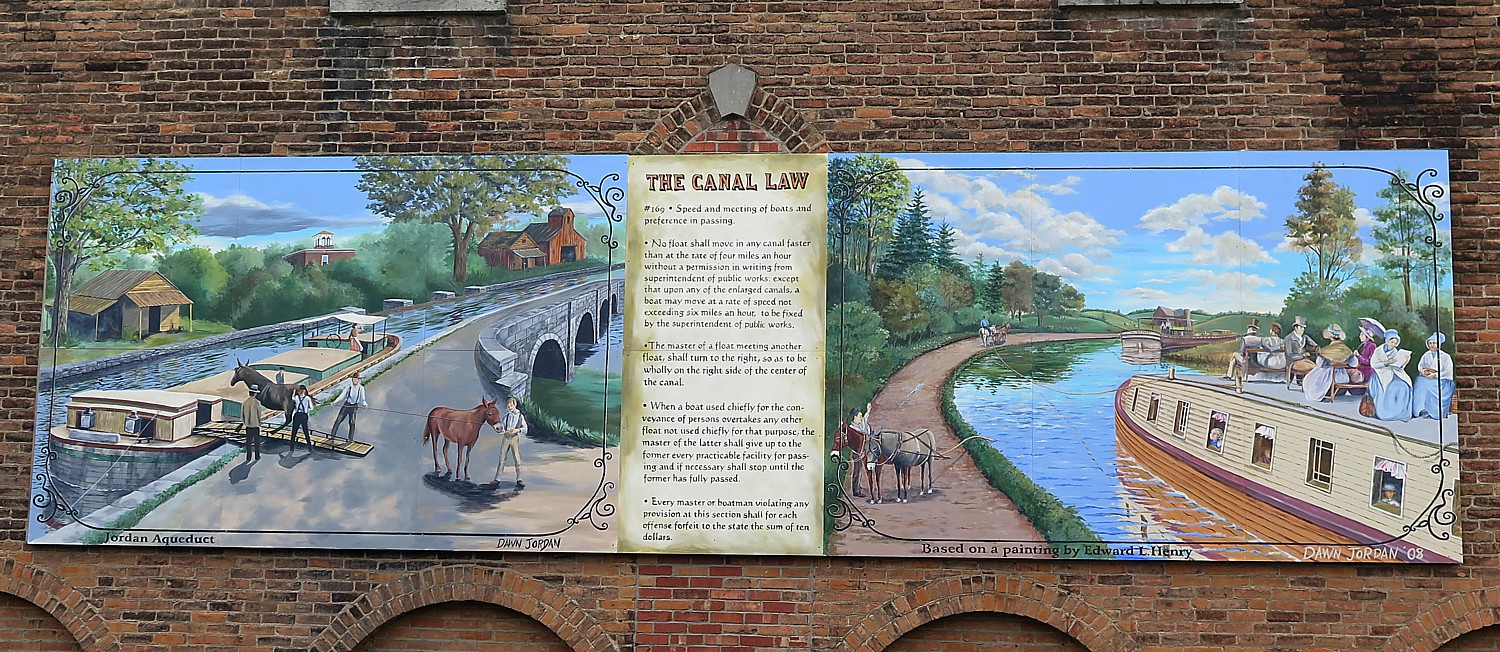

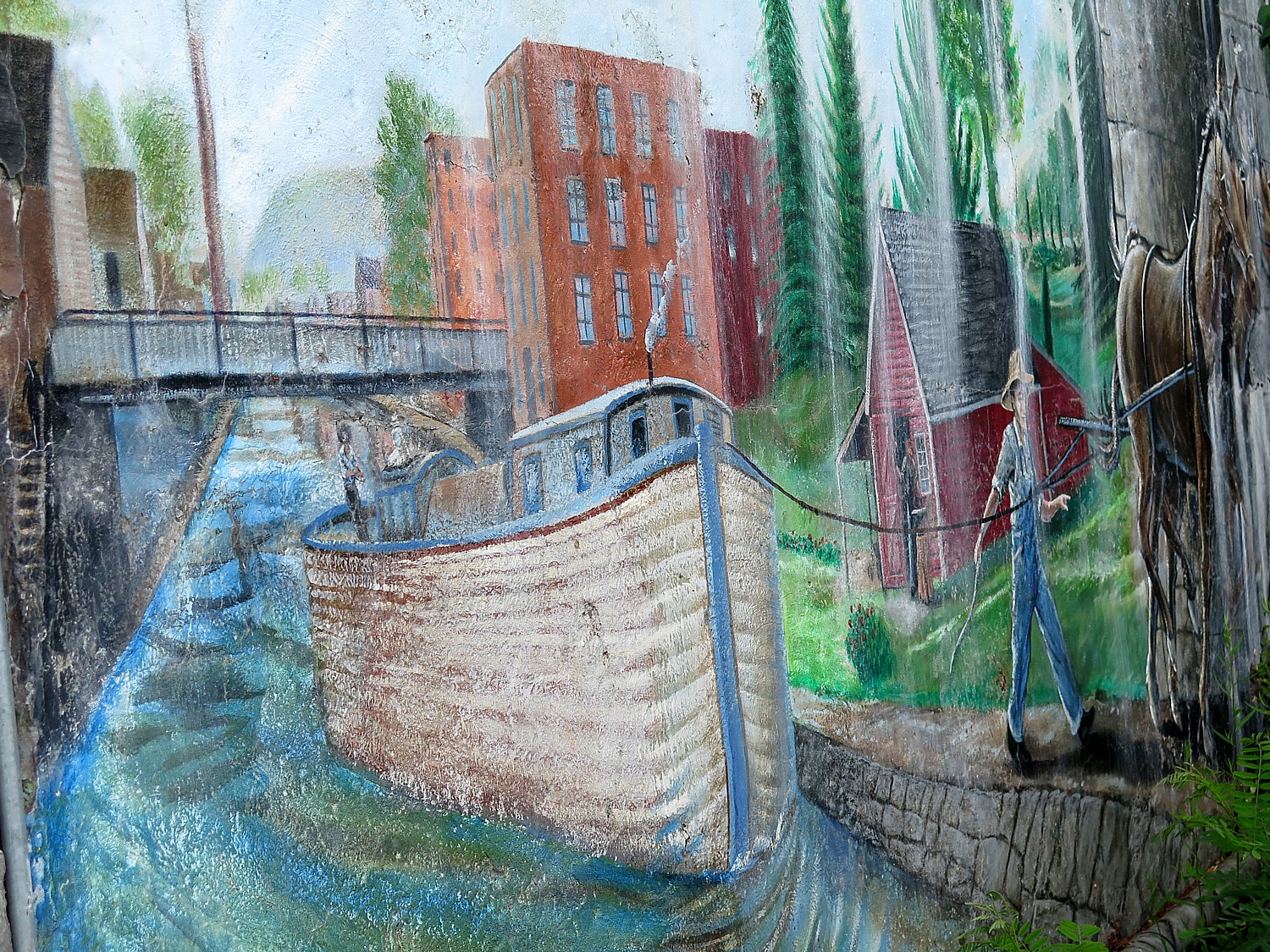

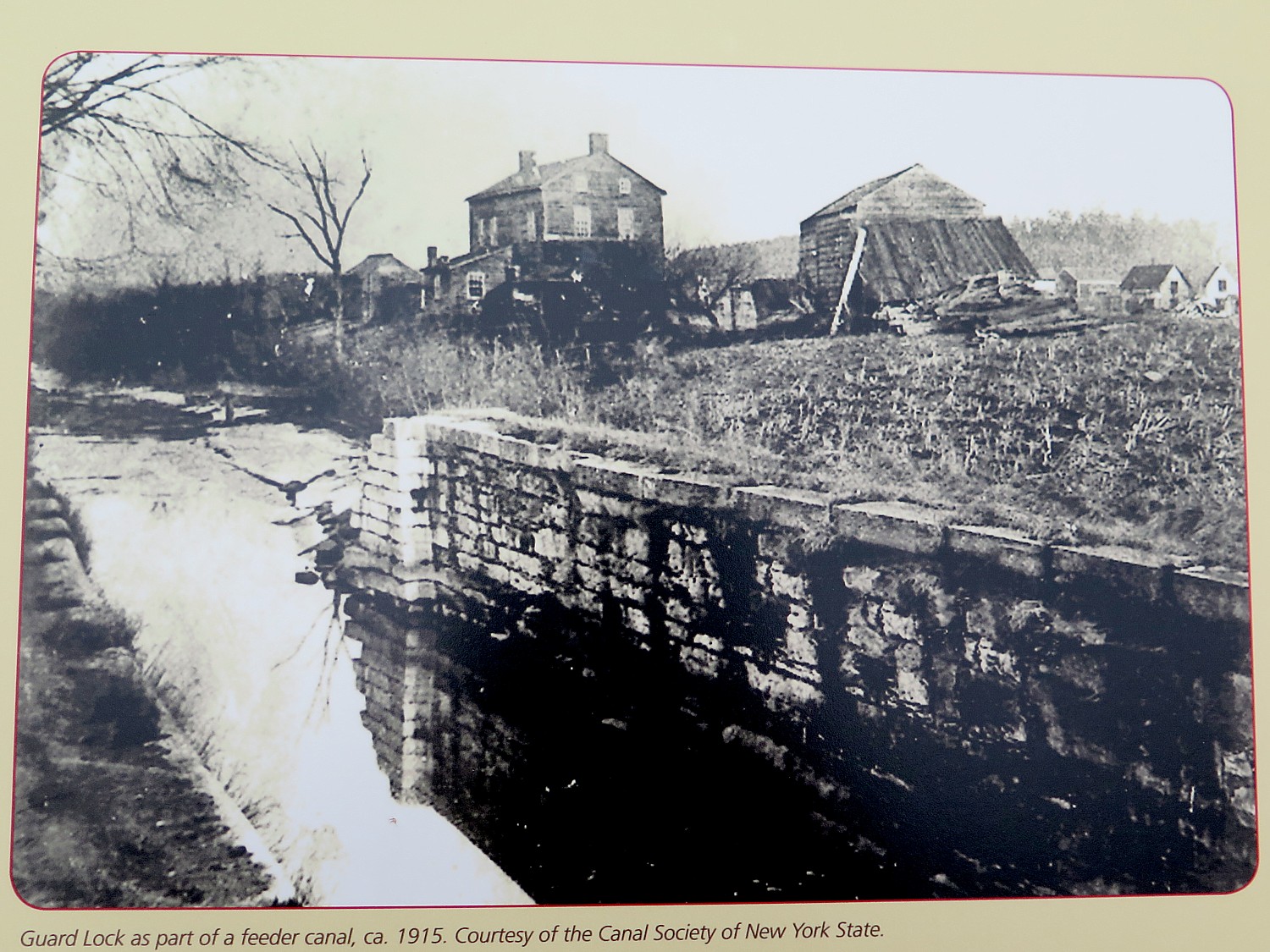

Most interesting at Schoharie Crossing is you can stand over the East Guard Lock – the original 1820s “Clinton Ditch” canal (now overgrown) – and see the same scene, minus water, as depicted in a historic photo.

Facing the other direction, standing beside the water, you can look over to what remains of the Schoharie Creek Aqueduct, built between 1835 and 1841 for the enlarged canal. This once grand 14-arch, 624-foot long aqueduct carried the canal above and apart from the Schoharie Creek (it enabled the canal to continue to function during flooding). The aqueduct was abandoned in 1917 when the Barge Canal opened on the Mohawk River, and over the years it declined so only six of the arches remain.

What remains of the Schoharie Creek Aqueduct © Karen Rubin/ goingplacesfarandnear.comA short bike ride further along the trail, you can visit Yankee Hill Lock #28 and the Putman Canal Store – the last double lock that was completed in eastern New York. The Putman’s Lock Grocery was constructed in 1856 and owned by the Garrett Putman family into the 1900s. (Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site, 129 Schoharie St., Fort Hunter, NY 12069, 518-829-7516, SchoharieCrossing@parks.ny.gov).

Mabee Farm

The initial appeal for me to join Parks & Trails NY’s annual Cycle the Erie bike tour was the exciting prospect of biking 400 miles, point to point, mostly without cars (and mostly on a flat trail), across New York State, with support services to carry our gear and host meals. But each and every day, I am pleasantly amazed at the array of sites to explore and discover. The Parks & Trails NY people who have designed the tour not only arrange visits at important sites along the way, but for morning and afternoon rest stops at interesting attractions that you might not have considered visiting on your own.

This is the case for our afternoon rest stop (at Mile 33.6), at the Mabee Farm Historic Site, which also houses the Schenectady Historical Society Museum.

Here, you can visit the Mabee’s 1705 Dutch-style Stone House, which was owned by the Mabee family until 1999.

This is one of the oldest homes in New York State and the oldest in the Mohawk Valley. It was first built in 1670 by Daniel Janse Van Antwerpen, who, it is believed, opened it as a fur-trading post. The property was sold to Jan Pieterse Mabee in 1705 and the house stayed in the Mabee family for a remarkable 288 years. It was given to the Schenectady County Historical Society in 1993 by George Franchere, the last descendant of the Mabee line, for the purpose of being a museum and education center.

It is a surprise to most who visit these colonial sites to learn that slavery was practiced here, beginning after Jan Mabee’s death in 1725 and ended 100 years later in 1827 with Jacob Mabee, his great grandson (when New York State abolished slavery). Among the 583 original documents from the farm are three bills of sale for slaves, wills giving slaves to children and a receipt from the Crown Point Expedition in 1755 when a trusted slave, Jack, was sent to Fort Edward and Lake George with supplies, two weeks before the Battle of Lake George.

“What is significant about the Mabee family is that they were ordinary,” the docent says.

Jan Mabee, born in Holland, bought the property from a neighbor in 1705, and lived in the cellar as he built the house. Jan and his wife Annette had 8 kids.

The house partly made out of stone; the wood beams are 1000 years old.

Jan was likely involved in the illegal trapping business. His wife was part Mohawk so they had a good relationship with the local Indians. The Dutch were tolerant and fair with the tribes (it was the British and French who cheated them).

Over the years, the house was turned into the Mabee Inn. Simon Mabee farmed the land and when he died, he left everything but the Inn to his son, Jacob; he left the inn to his two sisters.

It turns out that the Mabee farm is more than a history lesson, but a study of a dysfunctional family.

“Jacob was not a nice man. Jacob evicted them. He hired a carpenter and flipped the staircase around so they have no way to get up to the second floor. He built a new door. The sisters lived in one room. Jacob died 6 years later and the land passed to Margaret.”

Just outside the house is the family cemetery. You can visit the 1760s Nilsen Dutch Barn, see the beautiful Mohawk River flow alongside the site. Tied to the dock or parked behind the Dutch Barn is a reproduction 18th century bateaux, the De Sagar and the Bobbie G , which provides an idea of how goods were shipped up and down the river.

During our visit, a country fair is underway.

(Mabee Farm Historic Site, 100 Main St (Rte 5s), Rotterdam Junction, NY 12150, 518-887-5073, schenectadyhistorical.org/sites).

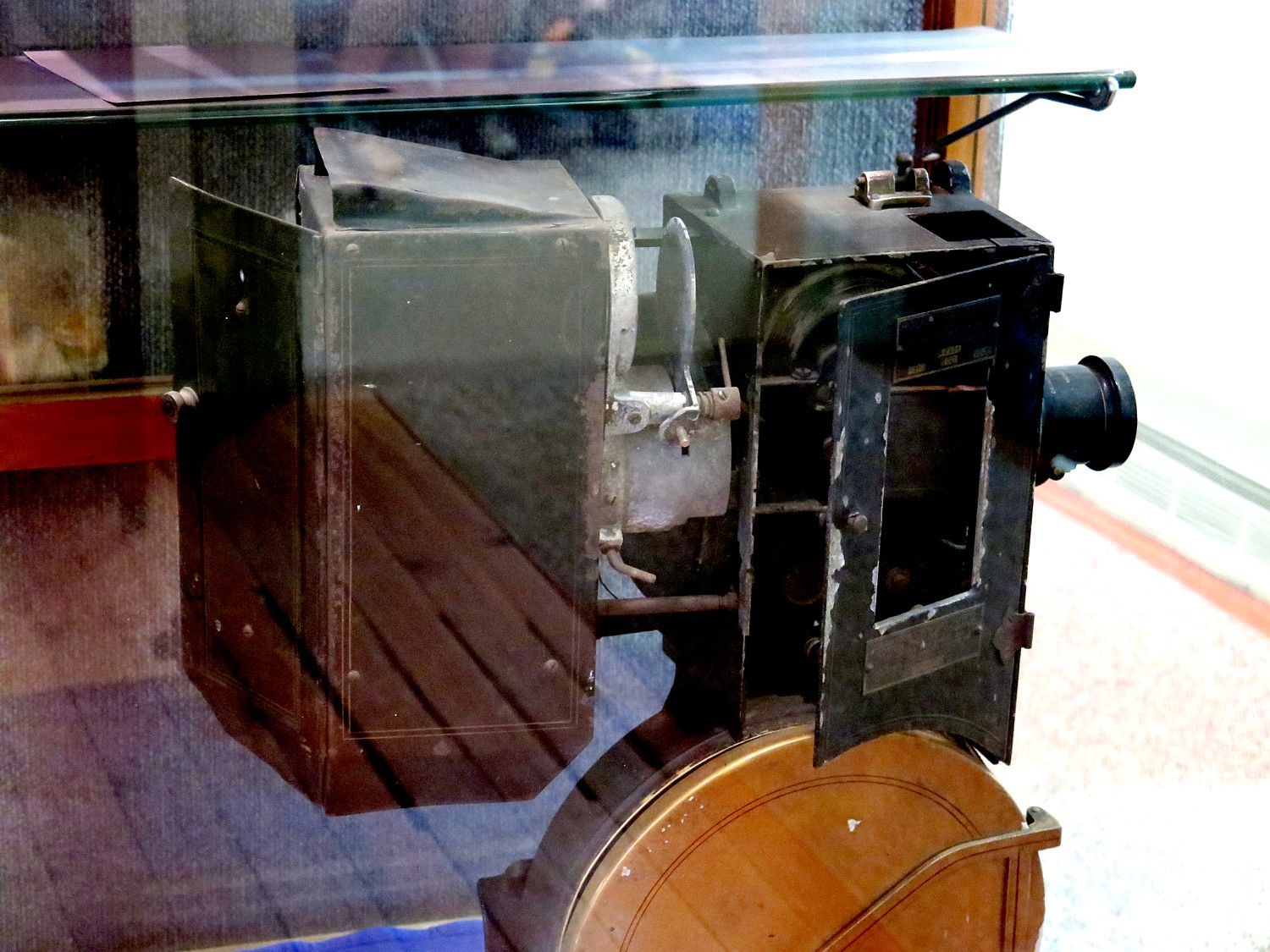

The Schenectady History Museum offers wonderful exhibits that follow the history of the county from the early settlers who traded with the Indians and farmed, to the 19th and 20th century. There is a collection of early American artifacts of the American Revolution era, the impact of the Erie Canal, and artifacts that show the role this area played in technological innovation and industrialization because of General Electric and the American Locomotive Company.

We ride a newly paved bike path into Schenectady.

In Schenectady, they have arranged for us to leave our bikes in a “corral” so we can explore the city.

I spend my time riding through The Stockade District. The oldest neighborhood in Schenectady, the Stockade District has been continuously inhabited for over 300 years, and is New York State’s first Historic District (since 1962) with an amazing assortment of historic buildings with more than 40 pre-Revolutionary houses and architectural styles that include Dutch Colonial, Georgia, Federal and Victorian.(You can access a cell phone walking tour at www.historicstockade.com.)

I pull myself away to finish the ride to get to the Jewish Community Center at Niskayuna, a suburban neighborhood of Schenectady, where we camp. This is an incredible facility with a country-club like outdoor pool (indoor pool also). I get there in time to swim.

This is the last night of our journey – and what a journey it has been. They have an elaborate “gala” dinner starting with beer and wine and hors d’oeuves, a fantastic catered dinner, and a “No Talent” talent show and a fashion show put on by the van drivers and baggage handlers of all the stuff that is still in the Lost & Found. And awards: like the most bones broken; the most crashes (5); most flat tires (4); the youngest solo peddling cyclist (8), the oldest cyclist (84). Side-splitting fun.

Day 8, Schenectady to Albany, 31 Miles

Our last day, the eighth of our 400-mile journey which began in Buffalo, is a breeze. Just 31 miles from Niskayuna into downtown Albany where most of us have parked our cars to take the bus to Buffalo for the start of the tour. The weather is perfect – sunny, cool.

The highlight of today’s ride comes at Mile 12: Cohoes Falls, one of the most powerful falls east of the Rockies which posed a major challenge for the Erie Canal engineers. Some of our riders who started in Buffalo were able to visit Niagara Falls and now are ending with Cohoes Falls, outside of Albany. What a way to bookend this journey.

Just next to the falls are 19th century brick structures, built as factories that have been repurposed to apartments.

Our ride takes us onto Peebles Island State Park, Waterford, where our final rest stop of our journey is arranged at the Erie Canalway Visitor Center. During the Revolutionary War, American forces prepared defenses here to make a final stand against the British. (518-237-7000, www.eriecanalway.org).

We ride through city streets – notable for the American flags that are flying – neighborhoods that have seen better days but nonetheless evoke a folksy feel of Americana.

Now, we come to the Hudson River, a goal in itself. We ride along a beautiful paved trail beside the Hudson that takes us into downtown Albany, New York State’s 300-year-old capital, and finally, cross the finish line, 400 miles.

You realize you haven’t just traveled 400 miles, but 400 years of American history, back to its very founding. And you understand so much better, the trajectory from colonialism and the clash of cultures with Native Americans, the transition from an agrarian economy to the Industrial Revolution, the wave of immigration and innovation, the progressive movements that followed and precipitated the explosive changes in society: labor, Women’s Rights, abolition. Most interesting of all, is how all of these seeds still flower in contemporary culture and politics. All of this unfolds before our eyes, mile by mile.

Biking adds an extra dimension to sight-seeing. It’s physical participation, an endorphin rush, an immersion. It puts you into the scene rather than merely observing – a participant, a part of the scene, rather than apart from it.

The tour is meticulously planned, well organized and supported, and how we have such wonderful opportunities to meet people from around the country (36 states are represented) and around the world (travelers from a half-dozen countries are here). A gathering like this prompts such fascinating interactions as people share their backgrounds, perspectives.

All of us have been so impressed by how well organized the trip is – from the truck drivers who pick up and drop off our gear each day, to the people who set up our breakfast and dinners and the morning and afternoon rest stops, to the SAG drivers and the riders who are there to assist if we have a problem. To the lecturers, the massage therapist and bike mechanics who travel along with us like camp followers.

For those who prefer not to set up their own tent (or take advantage of “indoor camping”) there is Comfy Campers, the closest thing to “glamping”. You have the luxury of having someone set up tent so it’s ready when you arrive, especially if it is raining, where you get a remarkably comfortable air mattress to put your sleeping bag on (amazing what a difference this makes), and take the tent down in the morning so you can just hit the trail again. Not to mention a fresh towel each day! Also, they set up a separate comfortable sitting area under canvas with charging stations. Those who want can also pay for coffee in the morning.

We are told that the finish line right at the Albany visitor center closes at 2 pm; UPS is on hand for those who need to ship their bikes home; a shower is made available nearby at the North YMCA; the municipal parking lot where many of us have parked our car is just next door; our luggage is deposited in the parking lot behind the visitor center for us to claim; some of us will take the shuttle bus back to Buffalo.

This has been one of the best, most memorable trips I have ever taken because the end-to-end Cycle the Erie ride hits on all cylinders: physically active and challenging so you feel you have really accomplished something at the end; communal – being with like-minded people from all over the country and the world, rich in heritage, scenic, affording real exploration and enlightenment. It’s no wonder that so many of us (myself included) have done it multiple times. (On this trip, the oldest cyclist, 84-year old, has done the tour 12 times.)

Cycle the Erie is an annual event, but you can download the route and do it all, or do segments as you like. A novel way to do it is by houseboat through companies like Mid-Lakes Navigation Co., Ltd. (11 Jordan St., PO Box 61, Skaneateles, NY 13152, 315-685-8500, 800-545-4318, info@midlakesnav.com,www.midlakesnav.com, and take a bike onboard, providing a unique experience. (Be aware: they pull the plug on the Erie Canal – actually drain the water – from November through April).

The 20th Annual Cycle the Erie Canal ride is scheduled July 8 – 15, 2018 (www.ptny.org/canaltour). In the meantime, you can cycle the trail on your own – detailed info and interactive map is at the ptny.org site (www.ptny.org/bikecanal), including suggested lodgings. For more information on Cycle the Erie Canal, contact Parks & Trails New York at 518-434-1583 or visit www.ptny.org.

The entire Erie Canal corridor has been designated the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor, Waterford, NY 12188, 518-237-7000, www.eriecanalway.org.

More information about traveling on the Erie Canal is available from New York State Canal Corporation, www.canals.ny.gov.

See also:

Cycle the Erie: 400 Miles & 400 Years of History Flow By on Canalway Bike Tour Across New York State

Cycle the Erie, Day 4: Seneca Falls to Syracuse, Crossing Halfway Mark of 400-Mile Biketour

Cycle the Erie: At Fort Stanwix, Rome, Time Travel Back to America’s Colonial, Native American Past

Cycle the Erie, Days 6-7: Erie Canal Spurs Rise of America as Global Industrial Power

_____________________________

© 2018 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin , and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures