By Karen Rubin, with Laini Miranda and Dave E. Leiberman

Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

Travel is as much about resilience, adaptability and problem-solving, as it is about personal growth, rejuvenation, and human connection. And so, though our intent was to camp (mostly wild camping) for our 8-day expedition through Utah’s wilderness and immerse ourselves in the topography and indigenous culture, the forecast for the first half of our trip in mid-April was for temps down to the 20s. In fact, when we arrived, there was a fierce gale-force wind blowing at 60 mph that pushed our rental Jeep around and made it difficult even to open the door.

Laini and Dave have taken the temperature into account and fortunately booked a spacious two-bedroom AirBnB in Teasdale (https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/41151071) just outside Capitol Reef National Park for our first night, and a one-room cabin at Canyons of Escalante RV Park for two nights in Escalante (where Dave has arranged for delivery of winter-grade sleeping bags and pads from Moosejaw.com).

Laini and Dave – who are making their third trip back to Utah and have invited their friend Alli and me to join – have carefully planned the itinerary. Each day has its own highlight and each destination its own topography and character and therefore, the experience we have. At Capitol Reef National Park it is the colored rock formations; Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument (for hard-core adventurers) offers slot canyons and hoodoos; Lake Powell in the Glen Canyon Recreation Area is our boat expedition into the flooded canyon; Cedar Mesa offers hiking expeditions in search of cliff dwellings and petroglyphs; and Arches National Park offers the most dramatic, expansive landscapes.

Fortunately, during the course of our trip, just about all the hikes and experiences we have are new for Dave and Laini.

We land at Salt Lake City Airport and pick up an off-road Jeep capable of plowing through deep gravel and sand from Alamo, and set out for the four-hour drive. Laini has planned to stop off at Walmart in Provo along the way to pick up food and camping supplies, and we find a delightful coffee shop (Java Junkie) for a snack and what becomes our all-time favorite coffee (Isis Roasters’ Grogg).

We arrive at Capitol Reef in the late afternoon and (I suggest) we take advantage of the gorgeous light and weather and drive the Scenic Drive to get a sense of the park. It is utterly perfect – the warm light, rich colors – and we get such a wonderful introduction.

The Scenic Drive is a 7.9 mile (12.7 km) paved road, suitable for passenger vehicles. You would need about an hour and half roundtrip to drive the Scenic Drive and the two dirt spur roads, Grand Wash and Capitol Gorge which go into canyons and lead to trailheads. (You can follow the Park Service’s Virtual Tour: https://www.nps.gov/care/planyourvisit/scenicdrive.htm; the tour is free but you still need to pay the $20 park entrance fee when you drive the Scenic Drive – though my America the Beautiful Pass satisfies.)

(The Scenic Drive, Grand Wash, and Capitol Gorge roads can be closed due to snow, ice, mud, and flash floods. Check at the visitor center or call 435-425-3791, for possible road closures.)

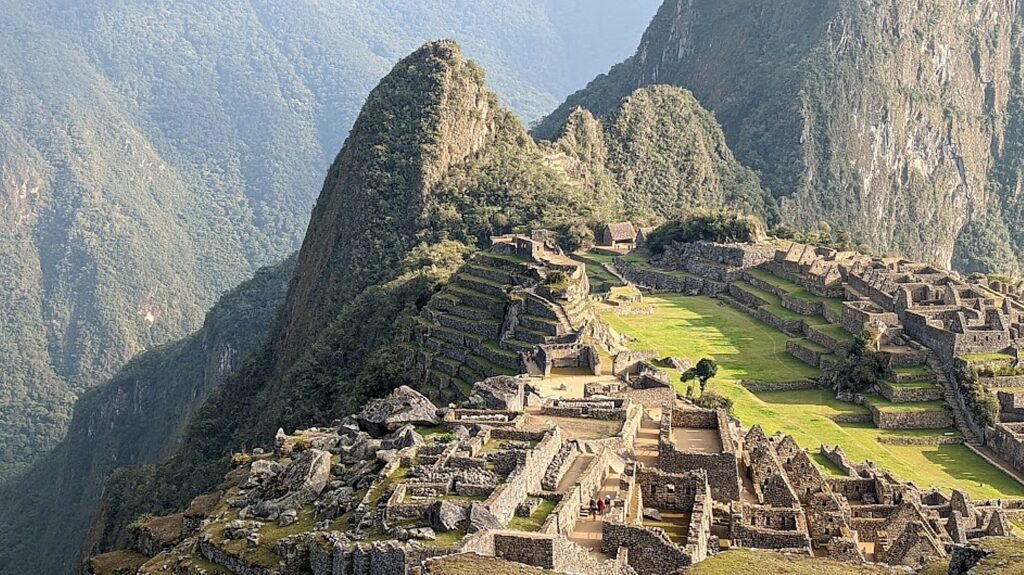

‘A Wrinkle in the Earth’s Crust’

“A Wrinkle in the Earth’s Crust” is the poetic description of Capitol Reef – referring to how this stunning landscape was formed. “The light seems to flow or shine out of the rock rather than to be reflected from it,” is how Clarence Dutton, a geologist and early explorer, described it in the 1880s.

Located in south-central Utah in the heart of red rock country, Capitol Reef National Park is a tapestry of cliffs, canyons, domes, and bridges. What makes Capitol Reef so special is how the rock layers tilt. The notes say that this was caused by intense crustal pressure which reactivated a fault buried deep beneath the sedimentary rock layers of the Colorado Plateau. This caused the overlying sedimentary rock layers to fold or bend into a one-sided slope called a monocline, which is uplifted 6,800 feet higher on the west side.

It is named the Waterpocket Fold because of the numerous small potholes, tanks, or “pockets” that hold rainwater and snowmelt and extends almost 100 miles from Thousand Lake Mountain to Lake Powell. The Waterpocket Fold has been impacted and shaped over eons by the geological processes of erosion, deposition, and uplift, all playing a part in the “drama” of Capitol Reef. This geologic feature is what accounts for the vibrant palette of constantly changing hues, as the light hits the towering cliffs, massive domes, arches, bridges and twisting canyons.

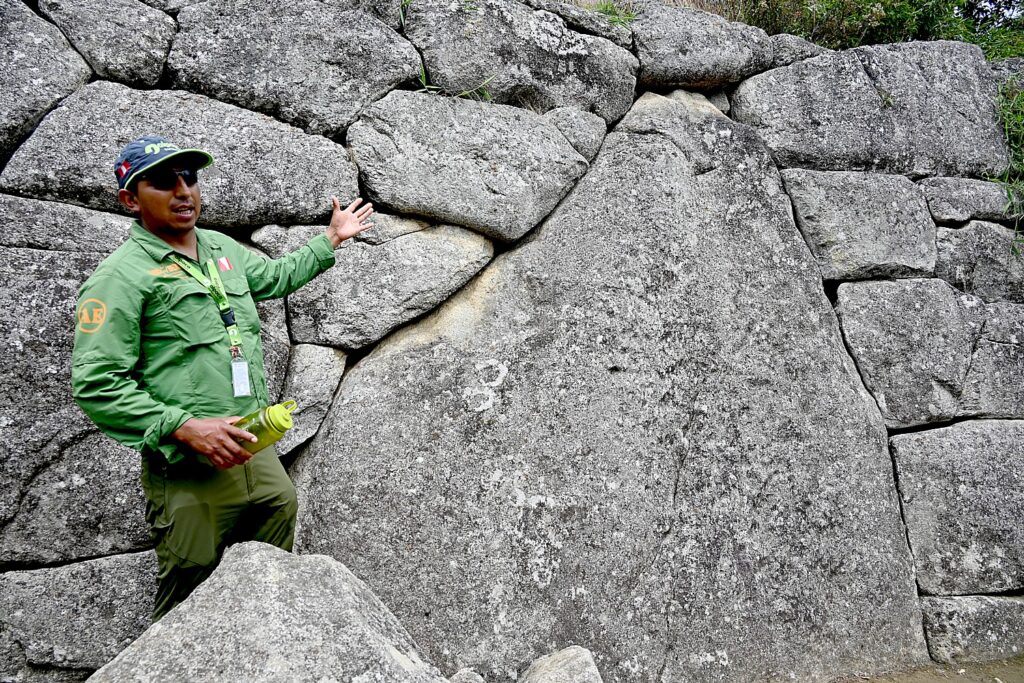

On the way back from our Scenic drive, we stop at a fascinating site, the Fremont Culture petroglyphs, not far from the Capitol Reef Visitor Center. The petroglyphs are reached after a short stroll on two boardwalks. The shorter boardwalk provides views of large, anthropomorphic (human-like) petroglyphs, zoomorphic (animal) petroglyphs of bighorn sheep and other animals, as well as geometric designs; the longer boardwalk parallels the cliffs and the petroglyphs along it are closer to the viewer but harder to see because of a patina that has developed over them.

The indigenous people who lived in what is now Utah for about 1000 years, from 300-1300 CE are known as The Fremont Culture, named by the archaeologists for the Fremont River canyon where they were first defined as a distinct culture. These petroglyphs (images carved or pecked into stone) are one of the most visible aspects of their culture that remains, according to the historic panels at the site.

Prehistoric people of Fremont Culture used area rock for tools and projectile points, and for the foundations of their homes. Clay was used for pottery, construction and to make figurines. Fertile floodplains supported crops of corn, beans, and squash along the streams of Capitol Reef until about 1300 CE.

(You can link to the audio guide, narrated by Rick Pickyavit, whose Southern Paiute ancestors lived here when the settlers arrived in the 1880s. https://www.nps.gov/care/learn/historyculture/fremont-culture-petroglyphs.htm)

Pickyavit says that unlike his ancestors, who were nomadic, the Fremont people settled in these canyons and became farmers and hunter-gatherers. It is not known if they were related to the better-known Ancestral Puebloans. What is known about the Fremont people’s daily lives comes mainly from artifacts and from these petroglyphs, but it is not known where they came from or why they left suddenly in the 13th century (though I believe it is now widely accepted that the people left after a historic, 20-year drought). “As you walk these paths and hidden places, do not even touch the petroglyphs. Protect their legacy, even as I respect it.”

It is natural to imagine the meaning of the images, but, Pickyavit says, “Caution must always rule in the interpretation of petroglyphs. With few exceptions, we cannot really be sure what the ancient maker of the petroglyphs had in mind. Some consider almost all petroglyphs a form of writing, while others consider most of them to be art, not writing. The large trapezoid-shaped human figures excite interest. Many have headgear and horns. Figures are commonly seen with necklaces, earrings and sashes. Animals, especially bighorn sheep, appear in many petroglyphs, indications that they were hunted and perhaps revered.”

I wonder, since these were created by different people in different times, isn’t it possible some were messages (writing, information) and some were art?

He notes that “Following the disappearance of the Fremont people in the 13th century, no one resided in the Waterpocket Fold country for 500 years. During this time, however, Ute and Southern Paiute hunters and gatherers roamed the region. They lived in close harmony with the natural environment and left little evidence of their presence.”

We stop in Torrey at the Torrey Grill and BBQ which offers a sheltered outdoor setting complete with firepit (we are still concerned about COVID) and is serving late.

The wind is still howling when we get to the AirBnB – home with gorgeous interior design, so cozy and comforting. I wake in the middle of the night to a blizzard – gale force winds, giant flakes of snow – that leaves 3-5 inches by morning. I feel (without hyperbole) we would have died –crushed under the snow or frozen to death – had we camped. I imagine us in some Survivor (or Disaster) movie based on fact (not the last time this image occurs to me during our Utah Adventure).

Hiking Capitol Reef National Park

Considering the weather, we phone the Visitor Center to get their recommendation for hikes, and the Ranger recommends Hickman Bridge and Cohab Canyon, both in the nearby Fruita area (435-425-2791). The snow, so gorgeous in the morning, is gone by the time we arrive at Capitol Reef but for some oddly frozen patches, and we have perfect winter hiking weather.

Both these trails are extremely popular – and for good reason.

Hickman Bridge Trail, just 1.8 miles roundtrip, is the most popular trail (so the most crowded): it is geologically fascinating, relatively easy, great for families, with each step offering stunning visuals – red rock with beige and blond striations, textures, overhangs – and eminently doable to get the full appreciation, with the climax of a spectacular arch. The hike encapsulates for us what Capitol Reef is about.

Along the Hickman Bridge Trail, you see high-desert views, traces of prehistoric American Indian culture, and evidence of the Civilian Conservation Corps’ work in the 1940s. After ascending through a scenic sandstone side-canyon, the trail loops under the grand 133-foot span of the Hickman Natural Bridge. This is considered a “moderate” trail, but I would say it is easy. What an introduction!

From the same parking lot (and when it’s popular, it may well be difficult to find a parking spot so you have to wait for one to open), you can walk something like two miles to one end of the Cohab Trail. We smartly decide to move the car to a small, dirt parking lot, 1.2 miles down the Scenic Drive from the Capitol Reef Visitor Center, diagonally across from the picturesque historic Pendleton Barn, to access the trailhead at the other end (actually it is the beginning). (If this dirt parking lot is filled, you can backtrack 2/10 mile and park at the picnic area.)

We have our lunch in the picnic area before starting out on the Cohab Trail.

Cohab Canyon trail is of easy-to-moderate difficulty with gorgeous vividly-colored rock formations and shapes. The first 0.3 mile is a tad steep (I’m glad I brought my hiking poles for this hike). A series of switchbacks lift you up 400 feet, all the while you gaze out at gorgeous views of the Johnson Mesa and Fruita Cliffs. But once within the canyon, the hiking is fairly easy.

Cohab Canyon is called a “hanging canyon” because it sits above the Fremont River floodplain. The entire trail is so beautiful – we come upon a few slots to explore, a 20-foot high mushroom shaped hoodoo (a tree is growing out of the top!) surrounded by slickrock, the Cohab Canyon arch, then some stunning overlooks of the valley and Fruita.

We opt not to do the whole hike, which goes 2.9 miles one way to the Hickman Trail parking lot (which would require taking a shuttle back, or, if you do the round trip, would take 4 hours). We hike in about 1.7 miles and return.

The two hikes – Hickman and Cohab Canyon – afford a very different experience, though both offer dramatic landscapes that are signature Capitol Reef. Hickman is well-traveled, ideal for families, and you feel like a tourist – but Cohab Canyon is all but devoid of other people so you feel the isolation (even if you do come upon another hiker here and there).

Laini had The Castle Trail hike on her to-do list but unfortunately, we don’t have the time. (It’s described as an old trail that apparently is no longer “advertised” to the enigmatic “back side” of the Castle, exploring a hidden canyon lined with mammoth boulders and violet-colored hoodoos, taking about two hours.)

You can see the cragged hunk of The Castle from just outside the Visitor Center. One of Capitol Reef National Park’s iconic landmarks, The Castle is a prominent sandstone formation made up of three primary layers: the bottom sandstone layer, the Moenkopi Formation, is 245 million years old; the middle gray-green layer, the Chinle Formation, was laid down as volcanic ash 225 million years ago; the top layer, including the Castle, Wingate Sandstone, formed 200 million years ago.

Also, though we didn’t hike Grand Wash on this trip, Laini and Dave hike it on their next one and highly recommend entering through the lower trailhead for an easy 20-30 minute walk through the most dramatic and narrowest part of the canyon, with towering walls over 100 feet overhead.

In the Fruita area, there are 15 hiking trails with trailheads located along Utah Highway 24 and the Scenic Drive. These offer a wide variety of hiking options from easy strolls over level ground to strenuous hikes involving steep climbs over uneven terrain near cliff edges. Round trip distances range from a mere quarter mile to 10 miles, and are well-marked with signs at the trailhead and at trail junctions and by cairns (stacks of rocks) along the way. Some trails have self-guiding brochures, available for a fee at the trailhead and visitor center.

The best detailed descriptions of these hikes are available at https://liveandlethike.com/category/utah/capitol-reef-national-park/

Capitol Reef also offers many hiking options for serious backpackers and those who enjoy exploring remote areas. Minimally marked hiking routes lead into narrow, twisting gorges, slot canyons, and to spectacular viewpoints high atop the Waterpocket Fold. Popular backcountry hikes in the southern section of the park include Upper and Lower Muley Twist Canyons and Halls Creek and in the Cathedral Valley area. A backcountry permit is required for camping outside of established campgrounds. The permit is free and can be obtained in person at the visitor center during normal business hours.

Capitol Reef offers so much to explore, Laini says, you really need more time there. Tourists overrun the main part, but there is a whole “backcountry” side that most miss.

See: https://www.nps.gov/care/planyourvisit/trailguide.htm and https://www.nps.gov/care/planyourvisit/hiking.htm

Scenic Byway 12

Driving out of Capitol Reef we come to an overlook just as the sun is at a perfect angle to make the red rocks blaze.

We drive 64 of the 124 miles of the Scenic Byway 12 to Escalante. Scenic Byway 12 is Utah’s first “All-American Road,” (and one of Laini’s favorite roads in the country) winding through vast slickrock benches and canyons. We reach the summit, 9,600 feet – and the temp has dropped to 15 degrees – with sweeping vistas of the Henry Mountains, Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument and Capitol Reef National Park.

Because the forecast had been for temps in the 20-30s, Dave and Laini booked a cabin at Canyons of Escalante RV Park, right in Escalante. It is one room for the four of us– very cozy (we still have to go outside for the bathroom, so we have that camping experience). And we’re able to have dinner at one of their favorite places from their previous adventures, Escalante Outfitters, serving up the best pizza outside of New York.

I find this day’s hikes in Capitol Reef perfect to acclimate and just become immersed in the spectacular scenery. And, I soon find out, these hikes are so very different from what we have yet to experience in the Grand Staircase-Escalante, where our Utah Adventure continues. Because Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is for more hardcore hikers.

Next: Grand Staircase-Escalante

______________

© 2023 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to [email protected]. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/KarenBRubin