By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

We finish our 62-mile ride on this third day of our 8-day, 400-mile Cycle the Erie biketour in Seneca Falls, renowned as the birthplace of Women’s Rights, where the organizers have arranged for the major sites, including the Women’s Rights National Historical Park, to stay open for us, and for a shuttle bus to take us from our campsite on the grounds of the Mynderse Academy into the downtown.

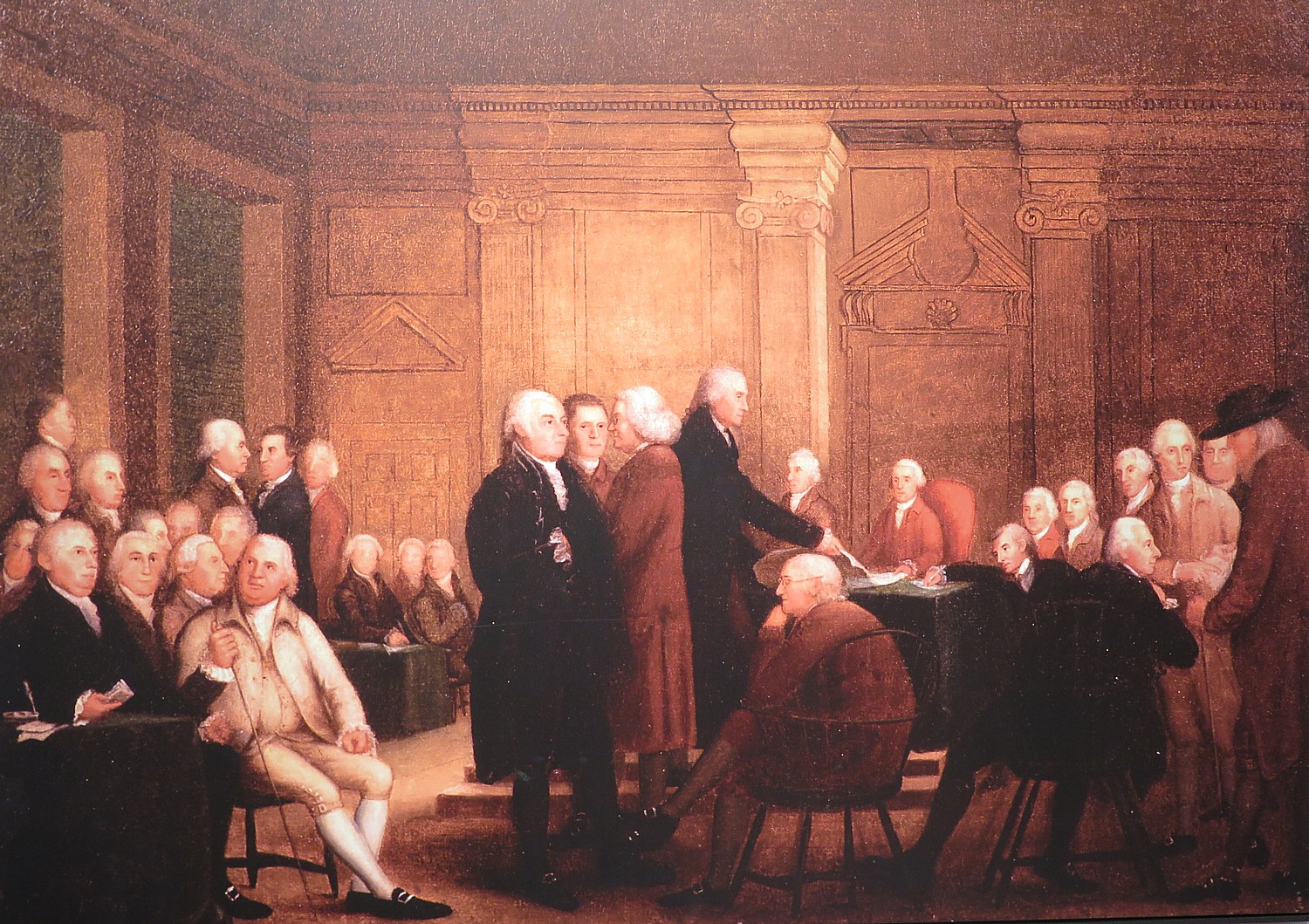

My impression of the Women’s Rights National Historical Park, operated by the National Park Service, has not changed from my first visit two years before: It is an absolute dud, especially when you consider the innovations in museums – especially compared to Fort Stanwix National Historic Site in Rome and the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse (both of which we will see in coming days). What is more, the NPS rangers who run the site know how antiquated and uninspiring – even disrespectful to women and the struggle for equality – the exhibit is and revealed a frustration in their inability to improve it.

There are no new insights or inspiration to be gained. The exhibit doesn’t have a clear theme, point or focus: is it about how and why the Women’s Rights movement started here in Seneca Falls (the influence of the Oneida Indians, which allowed women to become chiefs, have property and retain custody of their children, on Melinda Gage, for example; the prevalence of Quaker women among the early women’s rights leaders who had roles in their church; and the number of factories, spurred by the Erie Canal, which in turn employed women who subsequently wanted equal pay and to control their earnings)? Is it about the leaders of the movement, the courage they needed and how they persevered? What about exploring why it took 80 more years for women to get the vote, even after former slave men got their (theoretical) right to vote after the Civil War? Nor does it confront the controversies behind the continuing fight for women’s rights: why women still don’t earn as much as men for the same work, what is the “glass ceiling”. What role does the lack of affordable, accessible child care and healthcare play, and the mother-of-all controversies: why are women’s reproductive rights still so tenuous? And, oh yes, why are women still so underrepresented in elected office, including the highest office in the land, the Presidency?

What is glaringly obvious is that the exhibit reflects the 1980s Reagan perspective – more Phyllis Schafly than Gloria Steinem – a half-assed, slap in the face, disrespectful, condescending lip service to women’s rights and the ongoing struggle. If there is a theme, it is that women should be grateful for the opportunity to work in fields beyond teaching, secretarial and nursing – but nothing about pay equity or glass ceilings or sexual harassment. To Reagan (and now Trump), women’s rights are simply a way of supplying more workers and keeping wages low.

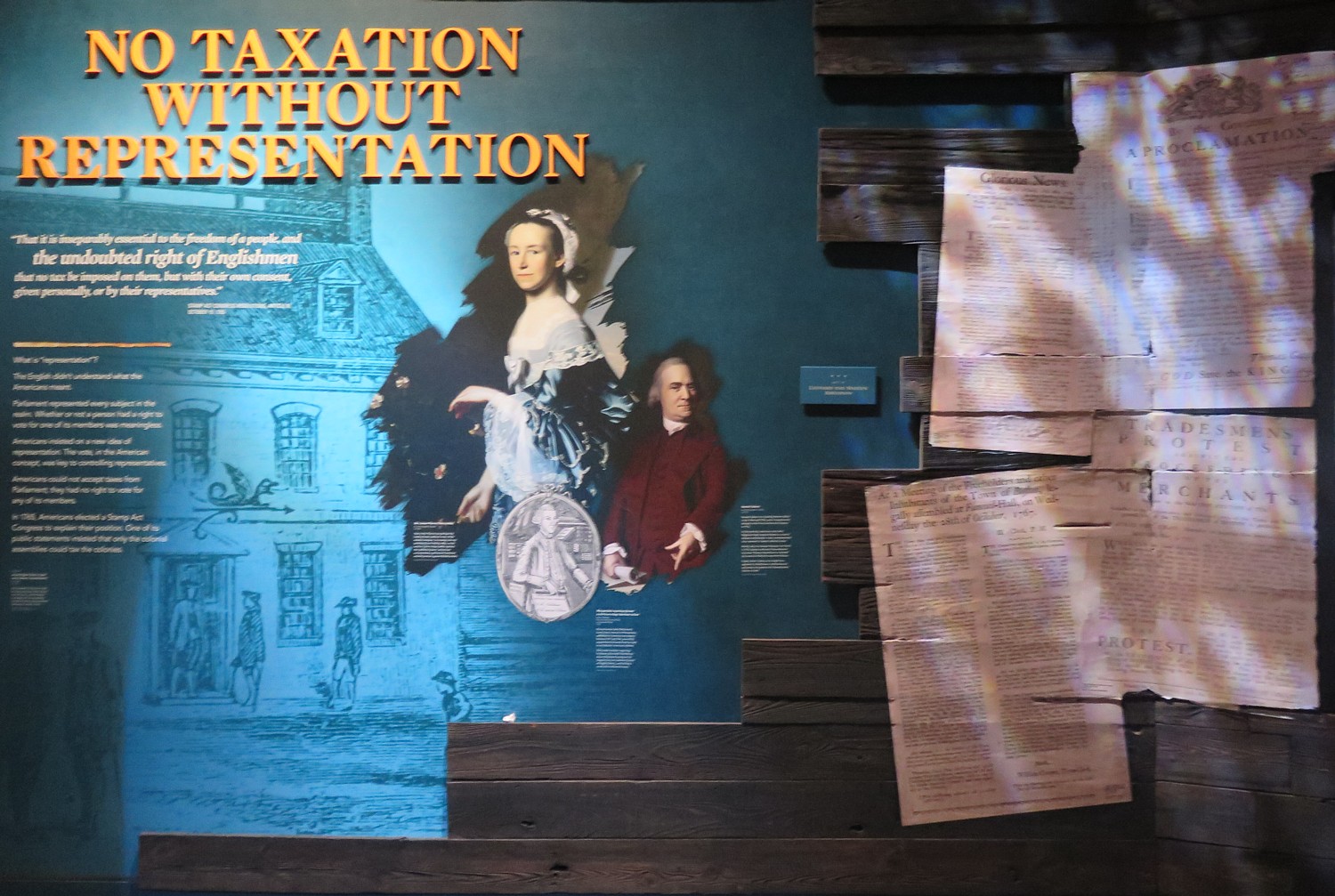

No discussion of how laws and the lack of anti-discrimination laws helped keep women down: How a woman could be raped, beaten, killed by her husband – was not much more than property (as were children) – and how a woman’s property became her husband’s. How women could be fired from jobs once married or pregnant or had children or reached a certain age or weight, or not hired at all merely because of gender. How insurance companies could charge women more (preexisting condition for being able to give birth). How landlords could refuse to rent to a woman without a husband’s signature; banks would not loan money for a home or business; how women couldn’t get a license to practice law. Sexual harassment”? The phrase was only invented in the 1970s, as the modern Woman’s Movement came into flower.

What did not having a vote mean for women in society? What happened when women were widowed or divorced? Why were there certain professions that women were steered into – like teaching, secretarial work, factories and nursing, positions which as a result tended to be woefully underpaid?

What was the role of the Church in suppressing women’s rights? That is, except for the Quakers who were the earliest advocates of women’s rights. What was the influence of the Oneida Indians, which gave women property rights, custody of children and the ability to become a tribal chief, on the early feminists including Melinda Gage (the mother-in-law of Frank Blum who wrote Wizard of Oz).

Where is the discussion of the women who opposed suffrage, equal rights (ie. Equal Rights Amendment, Phyllis Shafly), even the fact that Eleanor Roosevelt initially was not a supporter of women’s suffrage (until happened), and the women today who oppose a woman’s right to choose (then and still today)?

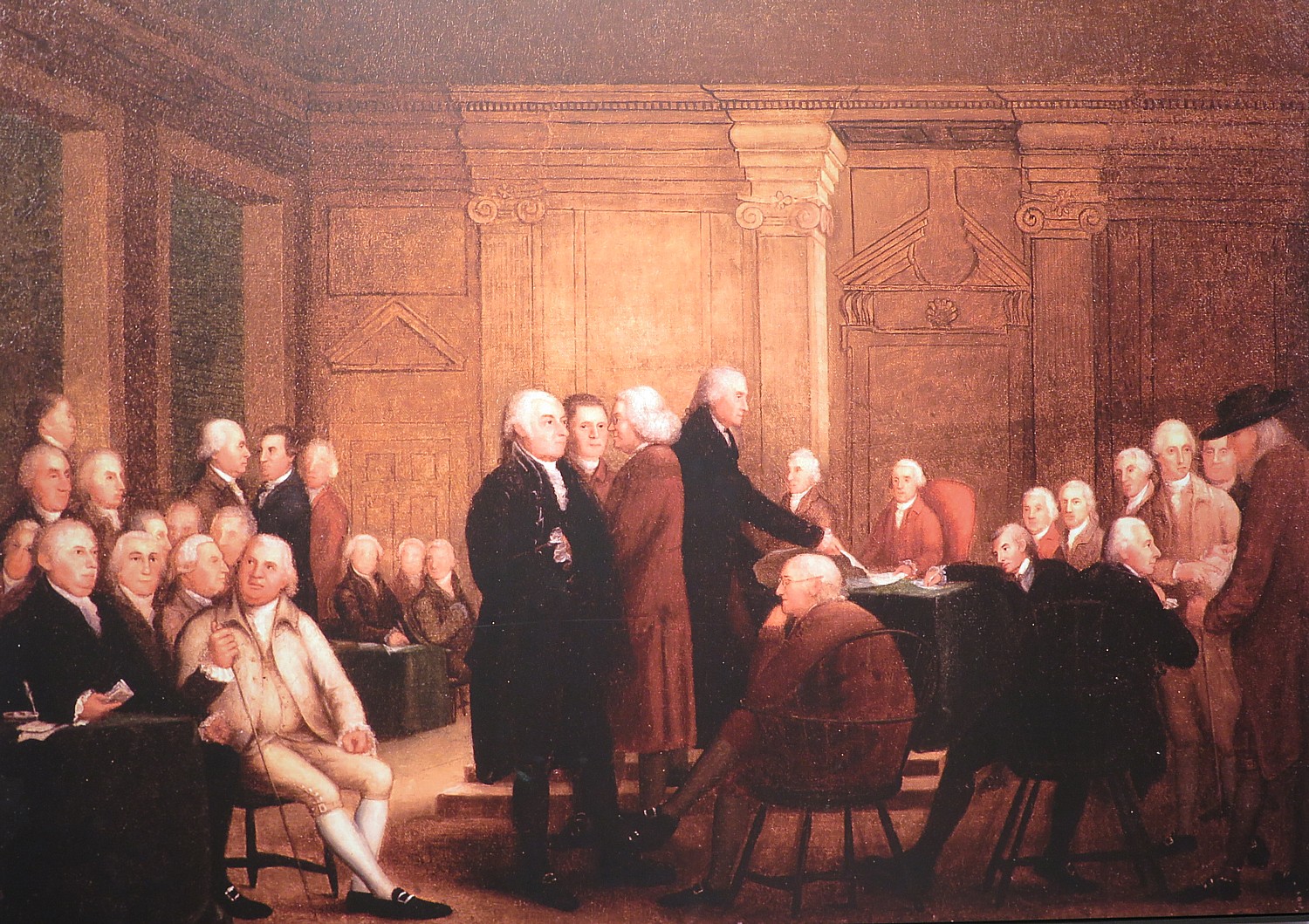

Instead of “women’s rights”, (and this is pretty typical of women’s issues generally) the exhibit goes off track into the bigger topic of civil rights (Abolition, the Underground Railroad). This should be seen in the context of how women were the backbone of the movement to end slavery, but after the Civil War, fully expected to win the vote along with freedmen, but instead only black men got the right to vote (such as it was, before Jim Crow). Also, it gives a nod to Jacksonian Democracy but doesn’t answer the question how white men without property got to vote without the need for a Constitutional amendment, but women didn’t get the vote until the 19th Amendment was finally ratified in 1920.

The exhibit is largely devoid of the heroic women (except for the sculpture) who fought for suffrage, and what the fight was like (locked up, force-fed).

There’s copy of Lily Ledbetter act signed by Obama in a case in the lobby, but no explanation or context.

There is a film in a lovely auditorium, “Dreams of Equality,” (delightfully cool and relaxing after biking 62 miles in the hot sun) which dramatizes the early internal debate over breaking out of the constrained role women were relegated to, is woefully and pathetically outdated – the historic elements aren’t bad but the pseudo “conversations” between girls and boys is frankly stupid and archaic.

But in the film, one of the main characters loses her husband in the Civil War and one woman says to the other, “If a woman had a say in making laws, there would be no wars,” to which the other woman replies, “If we had a say, who would listen?”

And in another bit of dialogue, the woman wonders, “Don’t women also have rights?” to which her brother responds, “What men most prize in a woman is affection.”

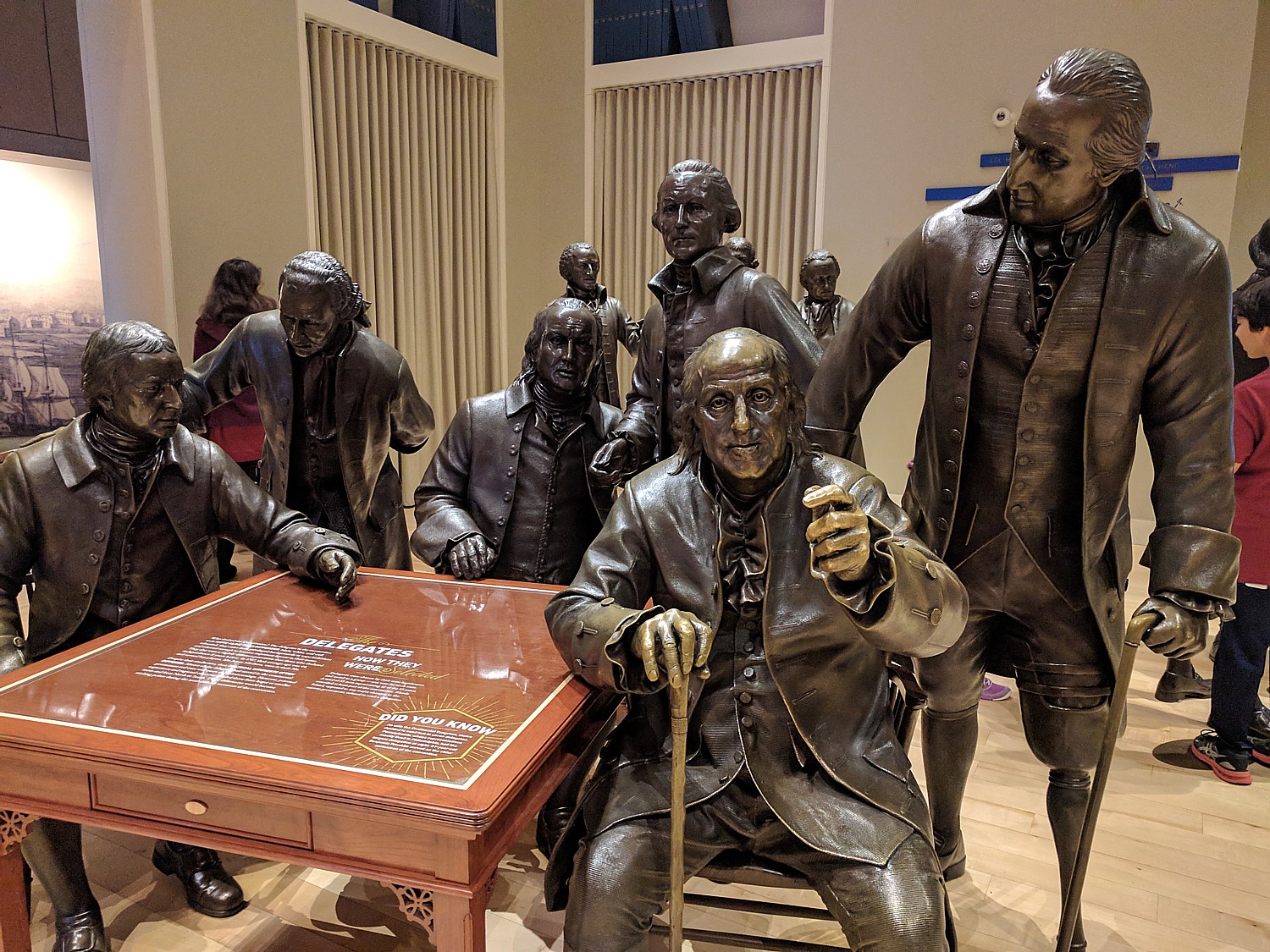

You also visit the Wesleyan Chapel where the first Women’s Rights convention was held in 1848 and the “Declaration of Sentiments,” modeled after the Declaration of Independence was signed. The structure’s history can be a metaphor for the ambivalence of American society to women’s rights: From 1843-1871 it was chapel, then an opera house/performing arts hall; then a roller skating rink, a movie theater (in 1910s), then a Ford dealership, and ironically enough, was a laundromat before facing a wrecking ball.

Women fought to save the building, and in 1982, during the Reagan Administration, it was turned into a national park.

(Womens’ Rights National Historical Park, 136 Fall Street, Seneca Falls, NY 13148, 315-568-0024, www.nps.gov/wori.)

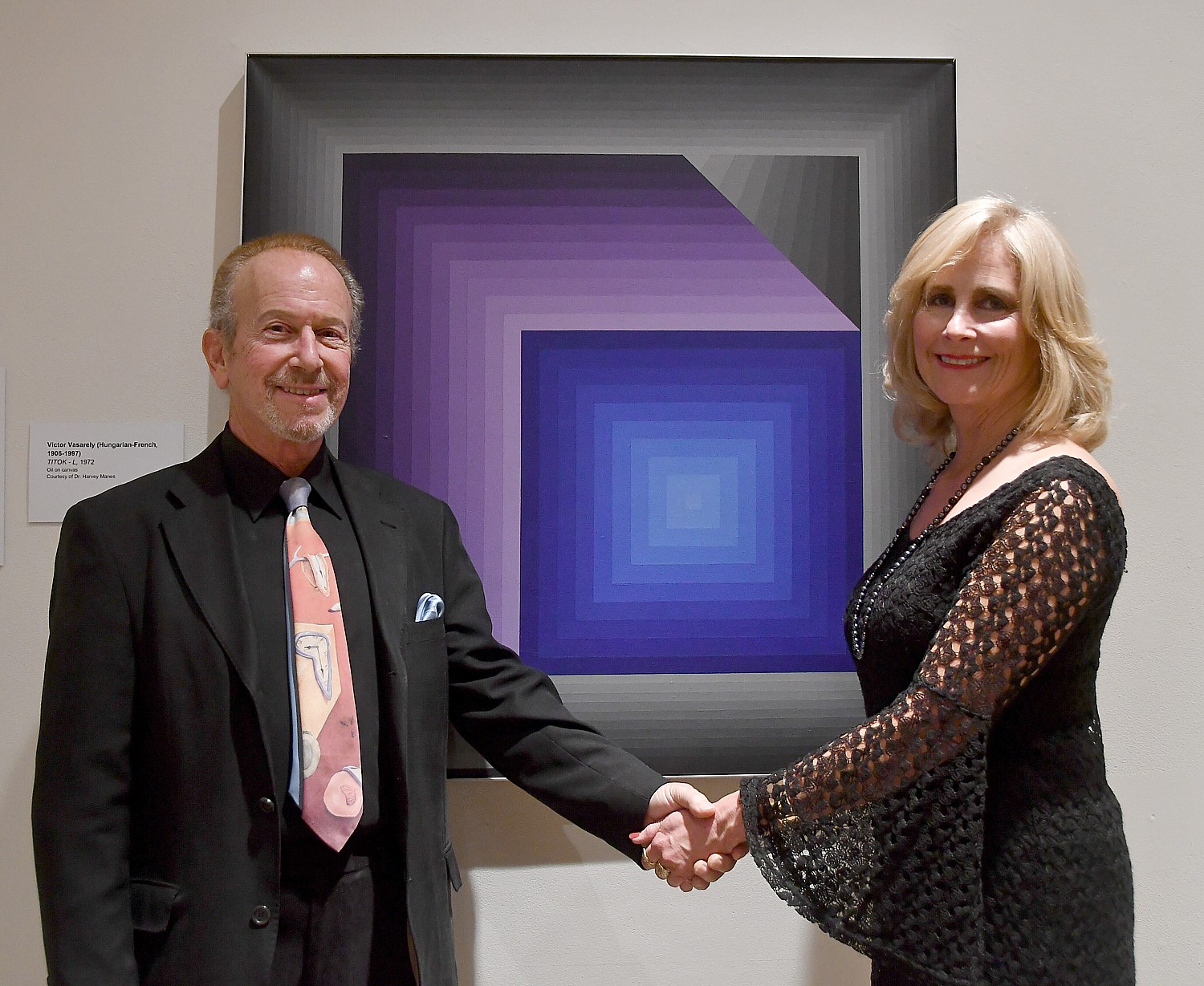

To put faces to the women’s movement, I walk down the main street to the National Women’s Hall of Fame. It is still in a ground floor storefront in a former bank building, awaiting its move into the factory building that was the Seneca Knitting Mill across the canal. This is most appropriate because the mill was where a number of the early feminists came from (they had a taste of earning their own money and were fired when they asked for wages equal to men).

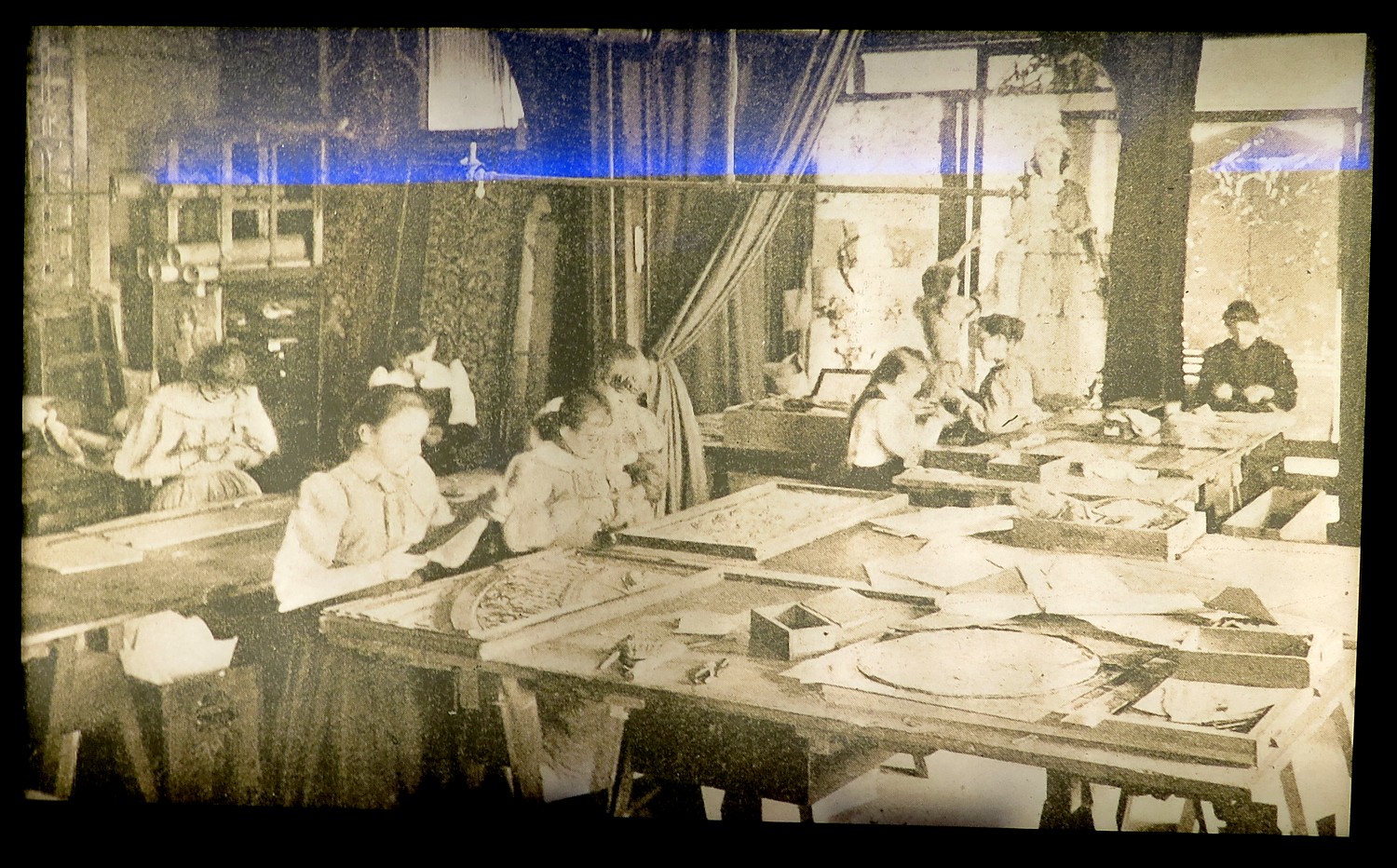

This massive factory, which dates from 1844, was owned by two men, Charles Hoskins and Jacob Chamberlain, who were among the 32 who supported women’s right and signed the Declaration of Sentiments which came out of the Women’s Rights Convention. That is saying something because out of the 300 people (40 of them men) who attended the convention in the Wesleyan Chapel in 1848, only 32 people signed the Declaration. The Seneca Knitting Mills, which operated until 1999 (can you believe it!), manufactured heavy woolen socks for 150 years, and then went the way of 50,000 other factories in the US.

The plan is to turn the 170-year-old limestone building into the hall of fame, research center and museum celebrating women and their accomplishments, to be called the Center for Great Women.

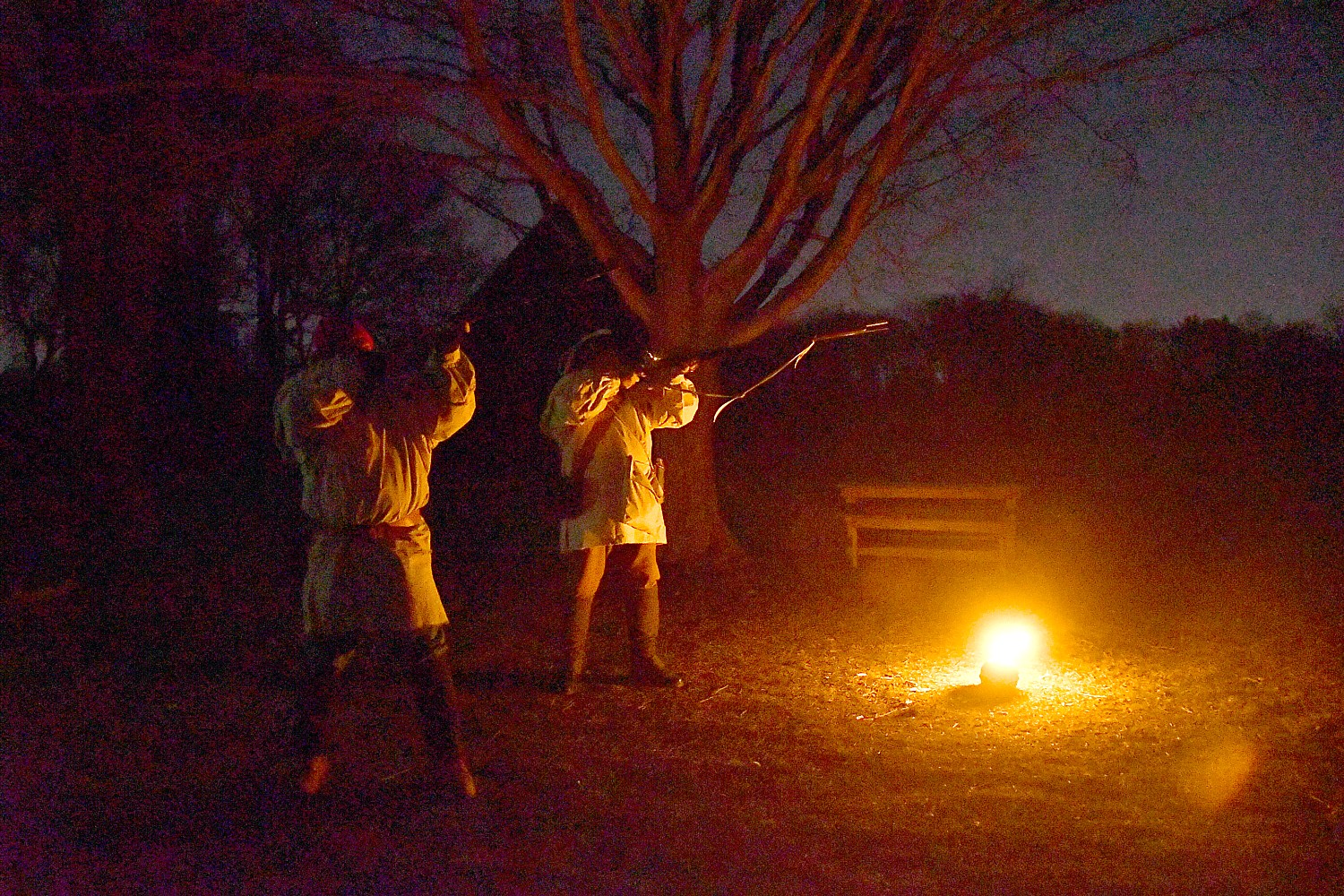

When I was in school, I could count on one hand the number of women who were presented as heroic figures – Madame Curie, Molly Pitcher (who I learn may have been fictional but still representative of women who took up the guns when their husbands were killed in the Revolutionary War), and the reporter, Nellie Bly.

I am thrilled to find Nellie Bly among the honorees. Her real name was Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman (1864-1922, honored in 1998), and was a trail-blazing journalist considered to be the “best reporter in America” who pioneered investigative journalism (hence the pseudonym); Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis, (1813-1876, honored 2002), who headed the committee that organized the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, MA in 1850, helped found the New England Women’s Suffrage Association and established Una, one of the first women’s rights newspapers; Amelia Bloomer (1818-1894), the first woman to own, operate and edit a newspaper for women, The Lily (first published in 1849 in Seneca Falls) and whose penchant for wearing full-cut pantaloons under a short skirt (as a protest to the way women were expected to dress), gave birth to the term “bloomers”.

It turns out there were dozens and dozens of women, going back to Colonial times, who did really important things. The women who are honored here are not necessarily honored as feminists, but for their accomplishments.

“Women’s stories are not told,” the organization notes. “Less than 10% of the content of history books references women. Students cannot name 20 famous American women through history, excluding sports figures, celebrities and First Ladies. Only 20% of news article are about women. A society that values women values all of its members. By telling the stories of great American women through exhibits and educational resources, the Hall will make a future where all members of society are valued a reality.” (Indeed, the New York Times, during this year’s Women’s History Month, began publishing obituaries of women who were overlooked in their own time.)

Founded in 1969, the Women’s Hall of Fame actually predates the Women’s Rights National Historic Park (one could say it even was at the very cusp of the Women’s Movement which really emerged in the 1970s). And when you contemplate the timeline of the biographies, you get a better understanding of the historical context of the Women’s Rights Movement.

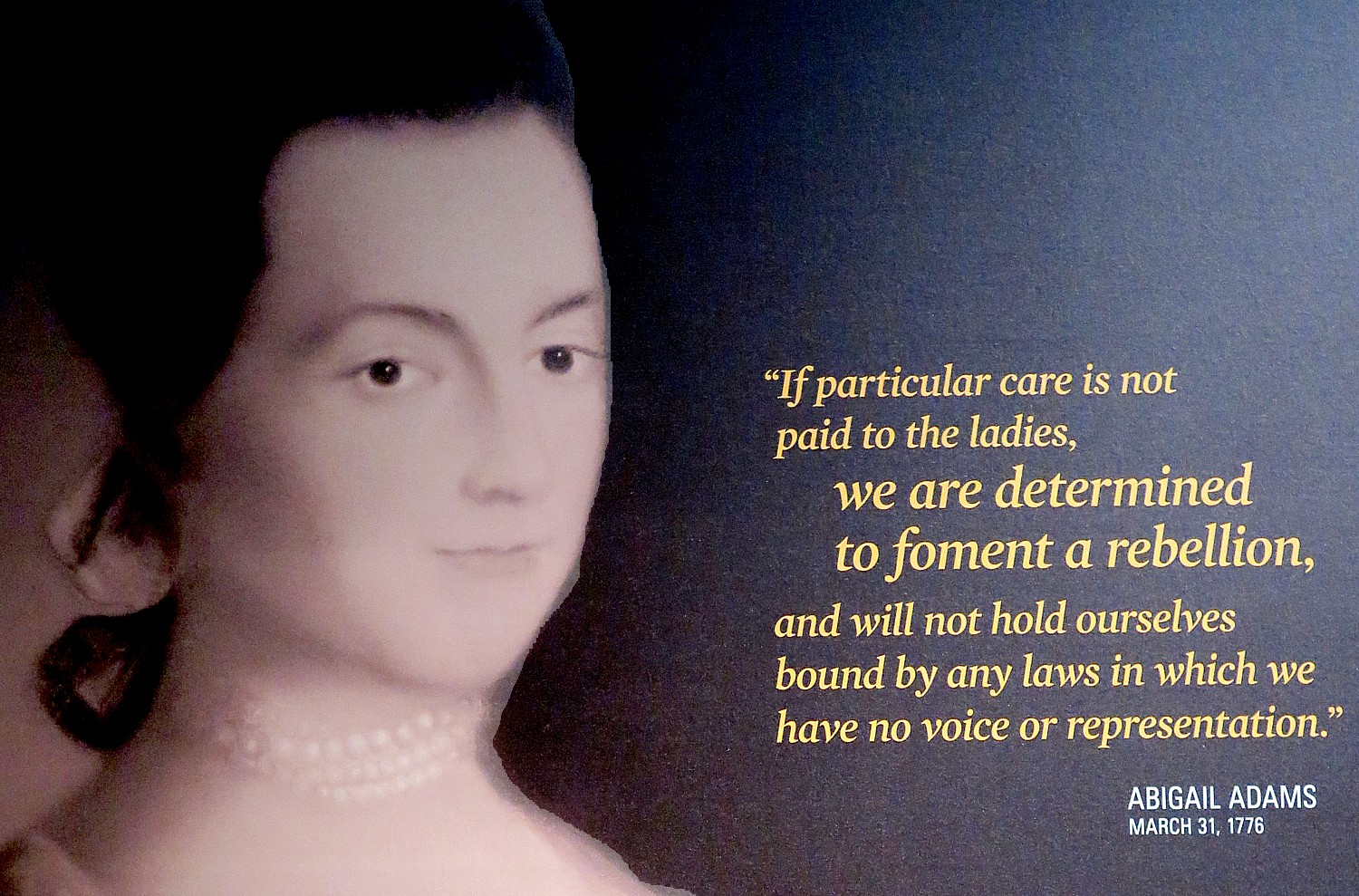

Looking around: Abigail Adams, what a pistol she must have been! She had such a strong influence on her husband but clearly was frustrated in the lack of opportunities women had to utilize their potential. (“Remember the ladies” in forming the new government,” she admonishes her husband, John Adams, in 1776).

Secagewea, Annie Oakley, Harriet Tubman. Jane Addams, Clara Barton, Margaret Bourke-White, Pearl S. Buck, Rachel Carson. Frances Perkins (Labor Secretary under Franklin Roosevelt), Eleanor Roosevelt, Anne Sullivan, Rosa Parks.

Of course, there are the suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony (there is a Susan B Anthony bench which came from the Ontario County courthouse in Canandaigua), but I also discover women identified as being early feminists (most you never heard of), and you realize that the struggle goes way, way back.

For example, Anne Hutchinson who lived 1591-1643 (honored 1994), was the first woman in the new world to be a religious leader and for it, was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony (there is a parkway in the Bronx named for her); Sarah Grimke, who lived 1792-1873 (honored 1998), who published papers championing abolition and women’s rights, and with her sister Angelina Grimké Weld, 1805 – 1879 (honored 1998), were southerners, born in South Carolina, who became the first female speakers for the American Anti-Slavery Society; Fanny Wright, 1795-1852 (honored 1994), the first American woman to speak out against slavery and for the equality of women; Mary Lyon, 1797-1849 (honored 1993), who founded Mount Holyoke in 1837, the first college for women, which became the model for institutions of higher education for women nationwide; and Maria Mitchell, 1818 – 1889 (honored 1994), an astronomer who discovered a new comet in 1847 and the first woman named to membership in the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, and a founder of the Association for the Advancement of Women.

Walking around (you can also peruse the website to find these biographies) I am introduced to all sorts of women I had not known, that fill me with pride: women on the front lines of science, civil rights, labor rights, education, human rights.

Mary “Mother” Harris Jones, 1830-1930 (honored 1984), a labor organizer and agitator who worked on behalf of the United Mine Workers and other groups; Sarah Winnemucca, c1844-1891 (honored 1994), Native American leader who dedicated her life to returning land taken by the government back to the tribes, especially the land of her own Paiute Tribe; Susette LaFlesche, 1854-1903 (honored 1994), a member of the Omaha Tribe and a tireless campaigner for native American rights; Julia Ward Howe, 1819-1910 (honored 1998), suffragist and author of “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” a lecturer on religious subjects, a playwright, an organizer of a women’s peace movement and advocate for women’s equality in public and private life; and Emma Lazarus, 1849-1887 (honored 2009), famous for authoring the words at the base of the Statue of Liberty, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” and an important forerunner of the Zionist movement.

There is the famous flyer Amelia Earhart but also Bessie Coleman, an aviatrix of the1920s, who was the first African American woman to have pilot’s license (at a time when women, let alone a black woman, were not allowed to have a license; Coleman went to Europe to get her license, what does that tell you?).

I so appreciate the diversity of the women represented, especially in the 20th century, when women do have more educational and professional opportunities: astronaut Sally Ride; tennis player Billie Jean King who broke through for women’s athletics; Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sandra Day O’Connor. Madeleine Albright, Bella Abzug, Oprah Winfrey, Lucille Ball, Dorothea Lange, Lilly Ledbetter, Margaret Sanger.

(Go to the website to see the most recent inductees as well as search all).

We commiserate over the life-size portrait of Hillary Rodham Clinton, who was already in the Hall of Fame as First Lady and New York Senator, the first woman to be a presidential candidate of a major political party, but should have been the first woman President.

It is remarkable to look at the faces and read the short biographies of women who have made such important contributions, going back to colonial times.

(National Women’s Hall of Fame, 76 Fall St, Seneca Falls, NY 13148, 315- 568-8060, www.womenofthehall.org)

Across the street, I stop in at the shop, WomenMade Products (how can you not?).

I have time to wander around. I try to get to the “Wonderful Life Museum,” but it is closed. It offers a brochure for a self-guided walking tour. Seneca Falls is supposed to have been the model for Bedford Falls in the James Stewart classic movie, though it is hard to recognize today. (See: “Seneca Falls History and Connections,” www.wonderfullifemuseum.com/seneca-falls-history-and-connections.)

I wander over to the canalside park just in time, 7 pm, to enjoy an old-fashioned band concert by the Seneca Falls Community Band (33rd season!); there is a stand selling the absolutely best ice cream in the world. Perfect.

Our campsite tonight is on the grounds of the gorgeous Mynderse Academy, which even has a flat-screen TV where a few of us gather around to watch the All Star Baseball Game.

The 20th Annual Cycle the Erie Canal ride is scheduled July 8 – 15, 2018 (www.ptny.org/canaltour). In the meantime, you can cycle the trail on your own – detailed info and interactive map is at the ptny.org site (www.ptny.org/bikecanal), including suggested lodgings. For more information on Cycle the Erie Canal, contact Parks & Trails New York at 518-434-1583 or visit www.ptny.org.

Information is also available from the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor, Waterford, NY 12188, 518-237-7000, www.eriecanalway.org.

More information about traveling on the Erie Canal is available from New York State Canal Corporation, www.canals.ny.gov.

Next: Day 4: Seneca Falls to Syracuse, Crossing Half-way Mark of 400-mile Biketour

See also:

Cycle the Erie: 400 Miles & 400 Years of History Flow By on Canalway Bike Tour Across New York State

_____________________________

© 2018 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin , and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to [email protected]. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures