By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

My third day of my deep-dive into Revolutionary War America in Philadelphia is devoted to exploring key figures and sites that I have never visited before: Benjamin Franklin Museum, the Betsy Ross House and the National Constitution Center.

Once again, the best way to connect is to walk because you are quite literally walking “in the footsteps” of these iconic individuals, and in so doing weave together the places and events, create a context. It is exciting to happen upon a site – a historic marker, a building keystone – that you would never have thought to seek out.

I set out again from my hotel, the Sonesta Downtown Rittenhouse Square, walking down Market Street, through City Hall, to Chestnut Street.

I am off to visit the Benjamin Franklin Museum, which is relatively new (open four years) and very close to the very new Museum of the American Revolution. The trick here is that you need to walk up an alley (I missed it the first few times I went by). I enter from Chestnut Street, but you can also come through from Market Street, where there is a row of townhomes (“Franklin’s Neighborhood”) that includes the post office, Franklin’s print shop, and looks back at City Hall.

Ben Franklin is, of course, a native son of Philadelphia, and justifiably the most revered figure, and here we learn why that is so deserved, why the city still has his stamp.

You enter a courtyard and come upon the “Ghost House” – the sculptural frame of Franklin’s home (the museum is actually in what would have been the basement) you can peek into the archeologically preserved remains of the foundation of his house. Franklin’s grandkids, unable to afford the “prohibitive” taxes, tore the house down in 1812 to sell to a real-estate developer. Eventually, a rooming house was built on the site. The National Park Service tore that down in the 1950s in order to restore the Franklin site, and after the Independence Bicentennial in 1976, it became a National Park, administered by the National Park Service.

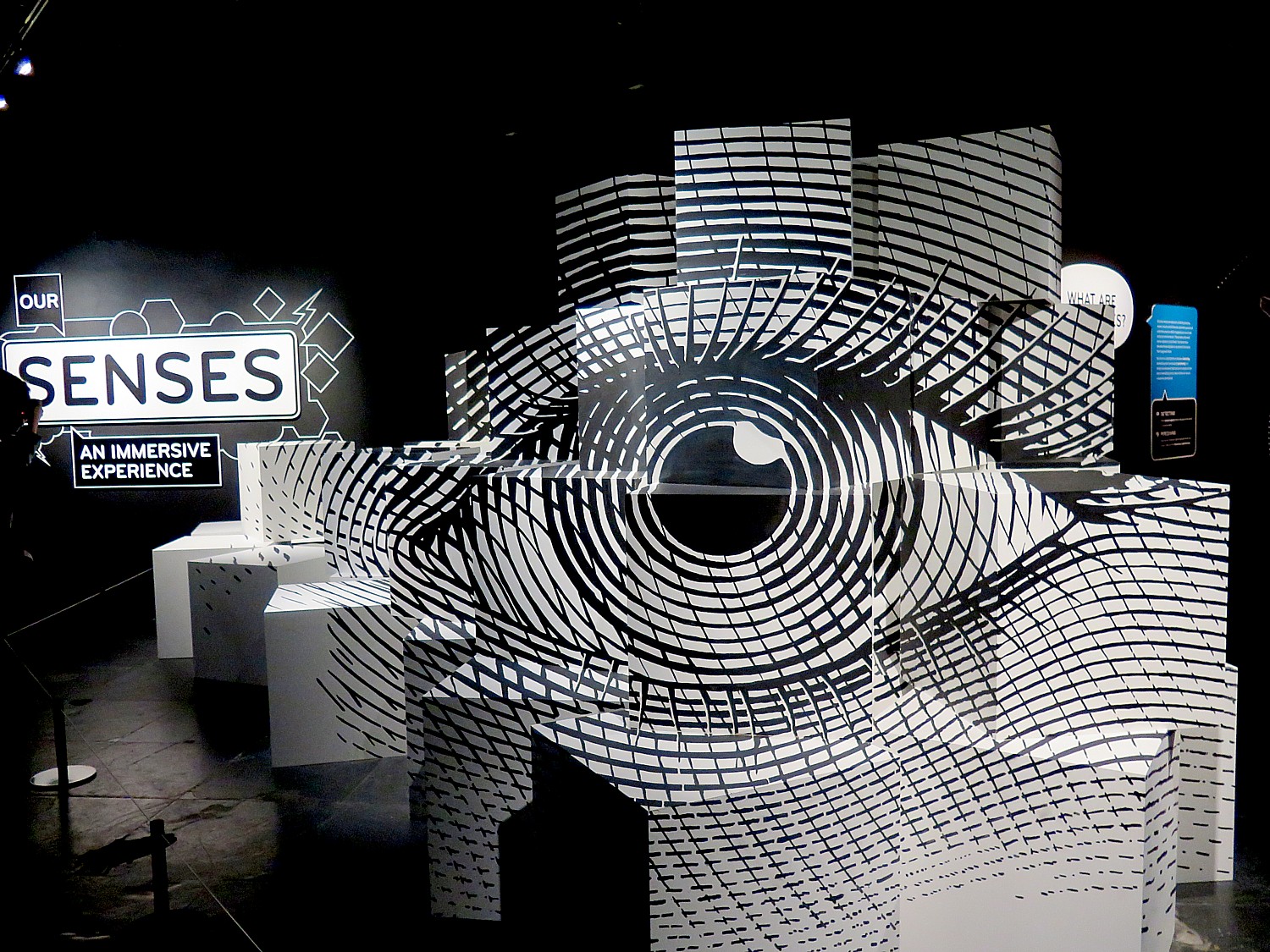

The exhibit area is divided into five “rooms” with each room interestingly focusing on a particular trait of Franklin’s: ardent and dutiful, ambitious and rebellious, motivated to improve, curious and full of wonder, and strategic and persuasive. There are videos, touch screen interactives, mechanical interactives, and artifacts in each area. An additional area called the “Library” presents a video with excerpts from Franklin’s Autobiography.

The exhibit is well presented to give a total biography of this fascinating Renaissance, self-made man, who so epitomizes the American Dream.

I come to Franklin Museum hoping to learn more of this fascinating man, and was richly rewarded. I did not realize his humble beginnings, or fully appreciate the range of his talents, accomplishments.

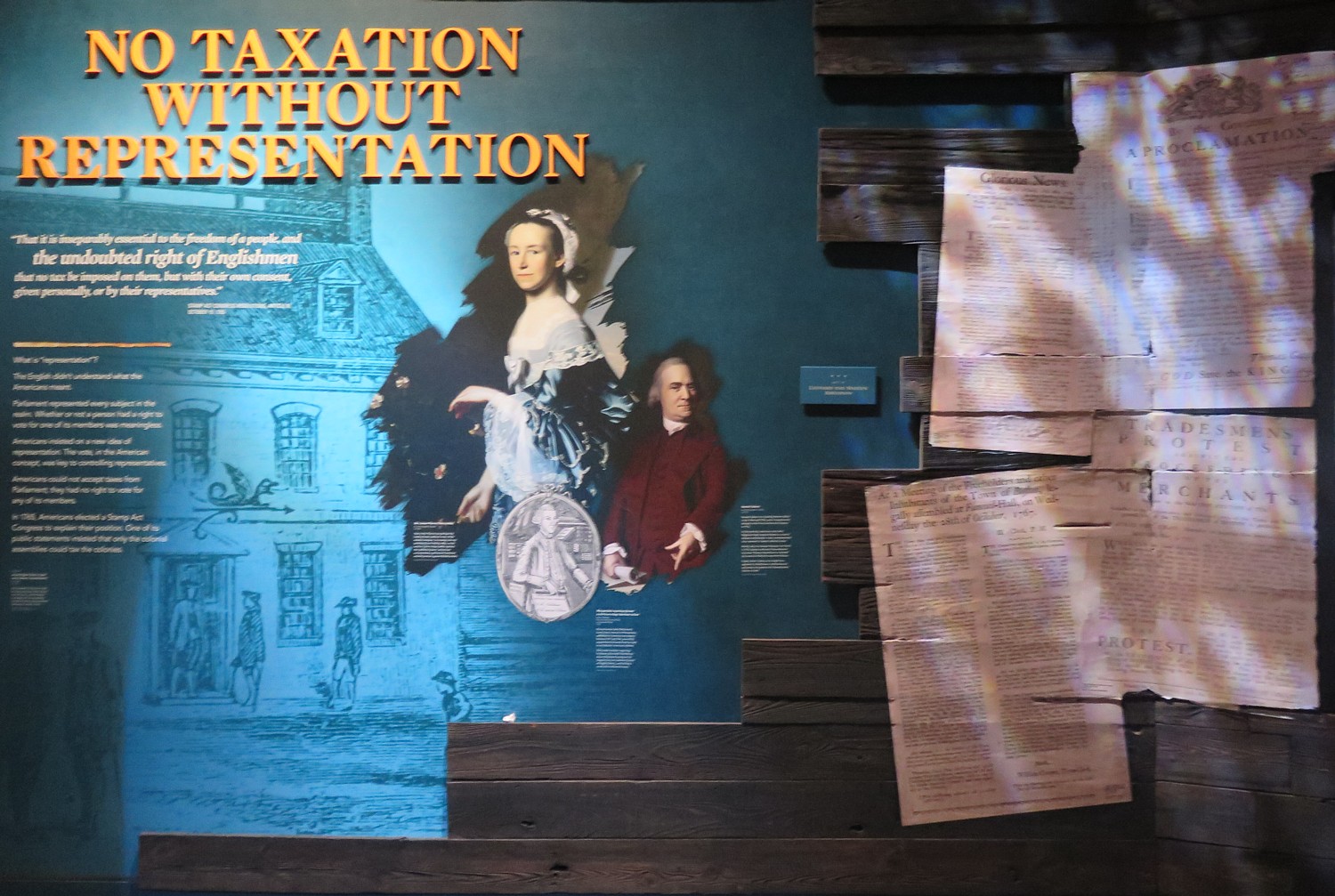

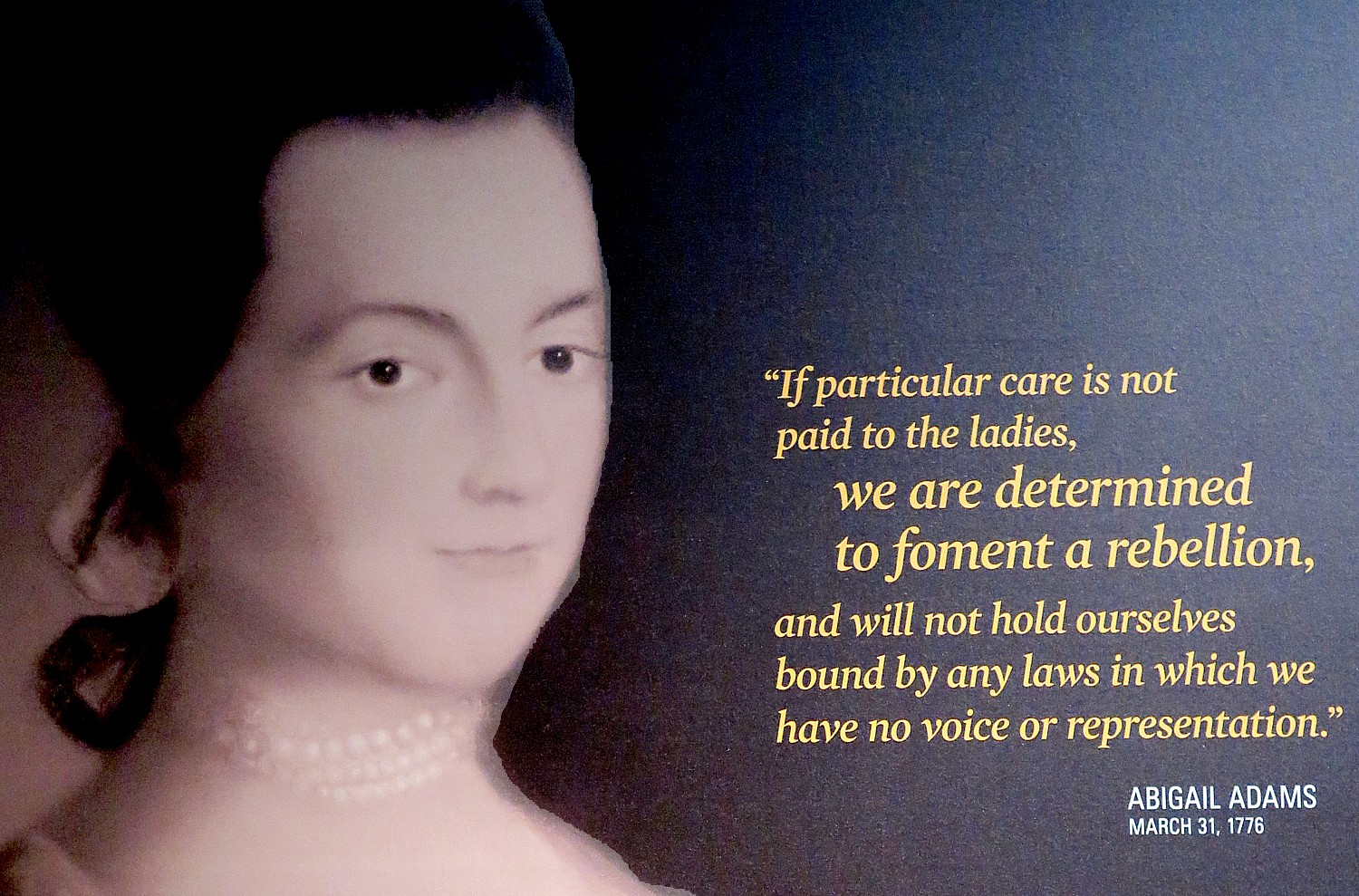

But my essential question about Franklin – my theory that it was the Stamp Act (not the tea tax) which imposed taxes on newspapers – that was the key to the colonists taking up arms to “free” themselves from the greatest superpower humankind had known. Franklin was not just a printer, but a newspaper publisher who provided seed money to newspapers throughout the colonies and became (what I consider) the first syndicated columnist, sending out editorials that would have been printed in those papers. My theory (as yet unproved) is that newspaper editors were the ones who turned opinion against British rule, gave the colonists the notion that they could actually win their independence, and gave the colonists from Massachusetts to Virginia, who were then (as now) very different, a sense of unity. Had the British not imposed the Stamp Tax, the newspaper editors may not have been so gung ho for Revolution. If my theory could be addressed at the museum, it was not at all clear to me.

But what is clear is that Franklin lived in the Age of Enlightenment – ideas and innovations were spread by trade and globalism – and people with the wit and wisdom like Franklin – despite having only two years of formal schooling – were encouraged to learn, innovate, invent not just technology (he did experiments with electricity and invented the lightening rod, bifocals, Franklin stove, urinary catheter and glass harmonica and charted and named the Gulf Stream) but civic society (volunteer fire department, the Philadelphia hospital, library, founded what became the University of Pennsylvania) and politics. There was greater willingness to challenge authority and notions of “divine right” – even question institutionalized religion – and class rather than be ruled by them. Colonists – who hailed from many countries in addition to Britain and would not have had loyalty to the Crown – had already lived in the New World for a century, and saw themselves not as British but as Americans. And Franklin knew better than anyone that a person from humble beginnings could ascend the ranks of social status.

I am surprised to learn that Franklin never patented his inventions, believing in the equivalent of what we call “open source.”

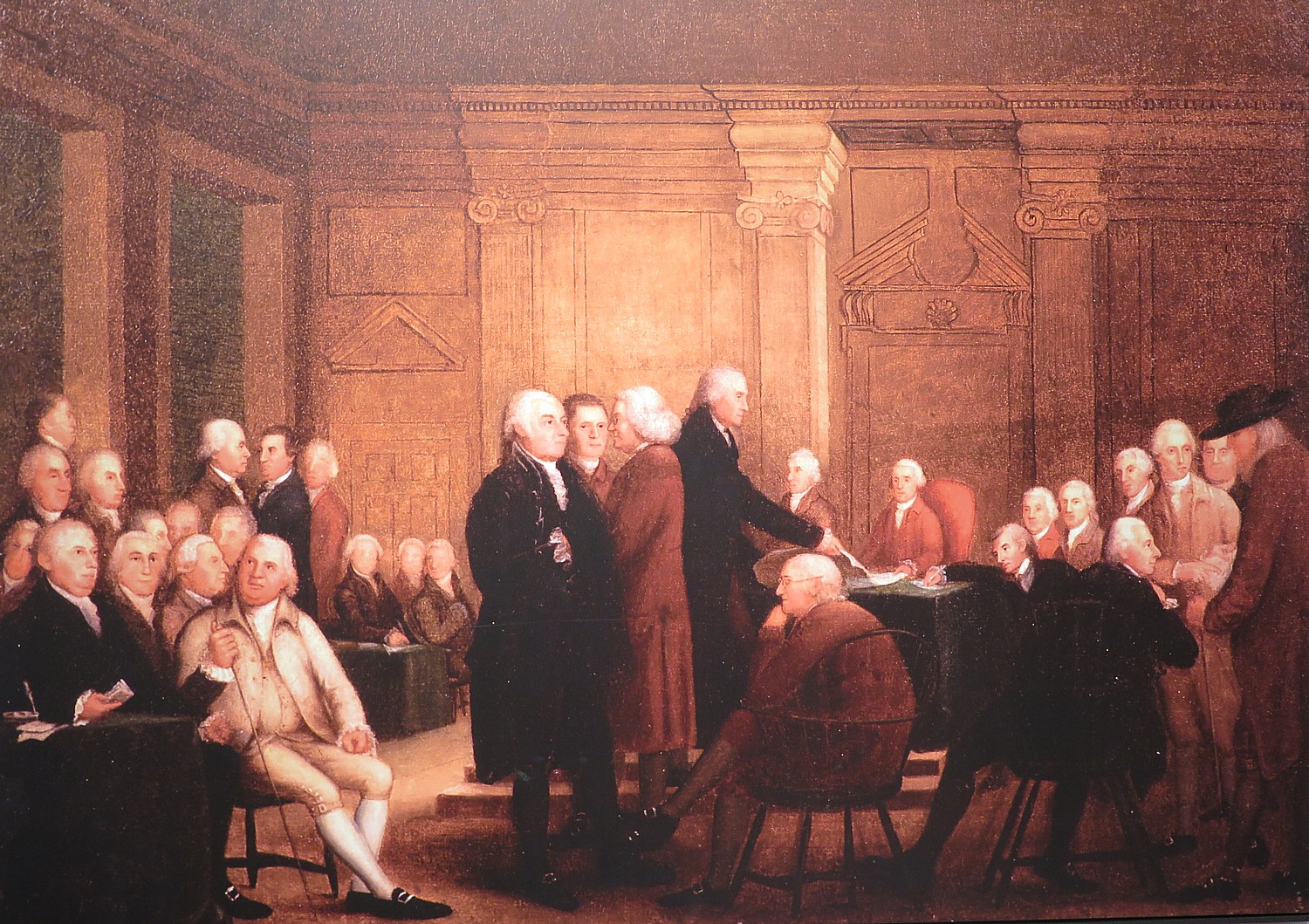

He was a key figure in creating the Declaration of Independence – one of the committee of 5 (with Jefferson, Adams, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston); and along with Adams nominated Jefferson to write the Declaration and made some important changes to Jefferson’s draft.

He was a generation older than Adams and was in his 80s during the Continental Congress – near death and in significant discomfort. He was considered a giant, an elder statesman, “The Sage.”

America’s ambassador to France during the Revolution, he secured critical support of the French.

I was shocked to learn that Franklin initially owned and dealt in slaves (it was a time when that was common place, even in the North) but by the 1750s, he argued against slavery from an economic perspective and became one of the most prominent abolitionists.

His personal background is worthy of a multi-part dramatic series:

Ben Franklin was born in Boston in 1706, one of 17 children of his father. He only attended two years of formal schooling which ended when he was 10; he continued his education through voracious reading.

At 12, he apprenticed to his older brother, James, a printer, who founded the first independent newspaper in the colonies. Ben started publishing columns secretly under a pseudonym (his brother was furious). When James, who was a free thinker, was jailed for three weeks in 1722 for publishing material unflattering to the governor, Ben took over the newspaper and wrote, in the character of his alter-identity Mrs. DoGood, “Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom and no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech.”

In 1723, Franklin escaped his apprenticeship and fled to Philadelphia, making him a fugitive. He took up lodging in the Read home, and at the age of 17, proposed marriage to 15-year old Deborah Read. But her mother refused permission for them to marry. Franklin went off to London for several years and Deborah married John Rodgers, who abandoned her, ran off with her dowry and but without a divorce, left her unable to remarry.

When Ben Franklin returned to Philadelphia, he formed a common-law marriage with Deborah who becomes a mother to Ben’s illegitimate son, William.(William grew up to become a Loyalist and self-exiled himself to London; William too had an illegitimate son who became Ben Franklin’s secretary and aide). Deborah and Ben had two more children together, but his son died at the age of 4 of smallpox; his daughter Sarah married, had children, and took care of Ben in his old age

I hadn’t realized that Franklin spent much of his life abroad, especially between 1757-1775, and as Ambassador to France from 1776-1785.

Franklin returned to the United States in 1787 and is the only Founding Father who is a signatory of all four of the major documents of the founding of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Alliance (1778) with France, the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolution (1783) and the United States Constitution (1787), though he was sick and suffering in pain during the Constitutional Convention.

When Ben Franklin died in 1790, 20,000 people attended his funeral. Later, I see where he was interred in Christ Church Burial Ground. It is interesting to note that in 1728, when he was just 22, Franklin wrote his own epitaph: “The Body of B. Franklin Printer; Like the Cover of an old Book, Its Contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be wholly lost: For it will, as he believ’d, appear once more, In a new & more perfect Edition, Corrected and Amended By the Author.” But the tombstone simply reads, as he specified in his final will, “Benjamin and Deborah Franklin.”

You leave the museum realizing what a remarkable Renaissance man Franklin was – like Thomas Jefferson in that way – with all the inventions and areas of success. Franklin was very much a modern man; if ever there was a person who could find himself 250 years in the future, he would have been very much at home in the 21st century. And very much Philadelphia’s Favorite Son for good reason.

The Ben Franklin Museum is a very welcoming space that really humanizes and personalizes Franklin. I love Franklin’s witty quotes, the portraits of him that show him throughout his life, even his love letters (to women not his wife).

For children, there is a scavenger hunt for the small squirrel figurines located throughout the exhibits. Franklin delighted in pet squirrels, or skuggs as they were known in his day.

You need at least an hour to visit.

The museum and print shop are operated by the National Park Service as part of the Independence Hall.

Open daily from 9 am to 5 pm. Admission $5/adult; $2/children 4-16.

Benjamin Franklin Museum, 317 Chestnut St., Philadelphia 19106, 215-965-2305, https://www.nps.gov/inde/planyourvisit/benjaminfranklinmuseum.htm

Print Shop

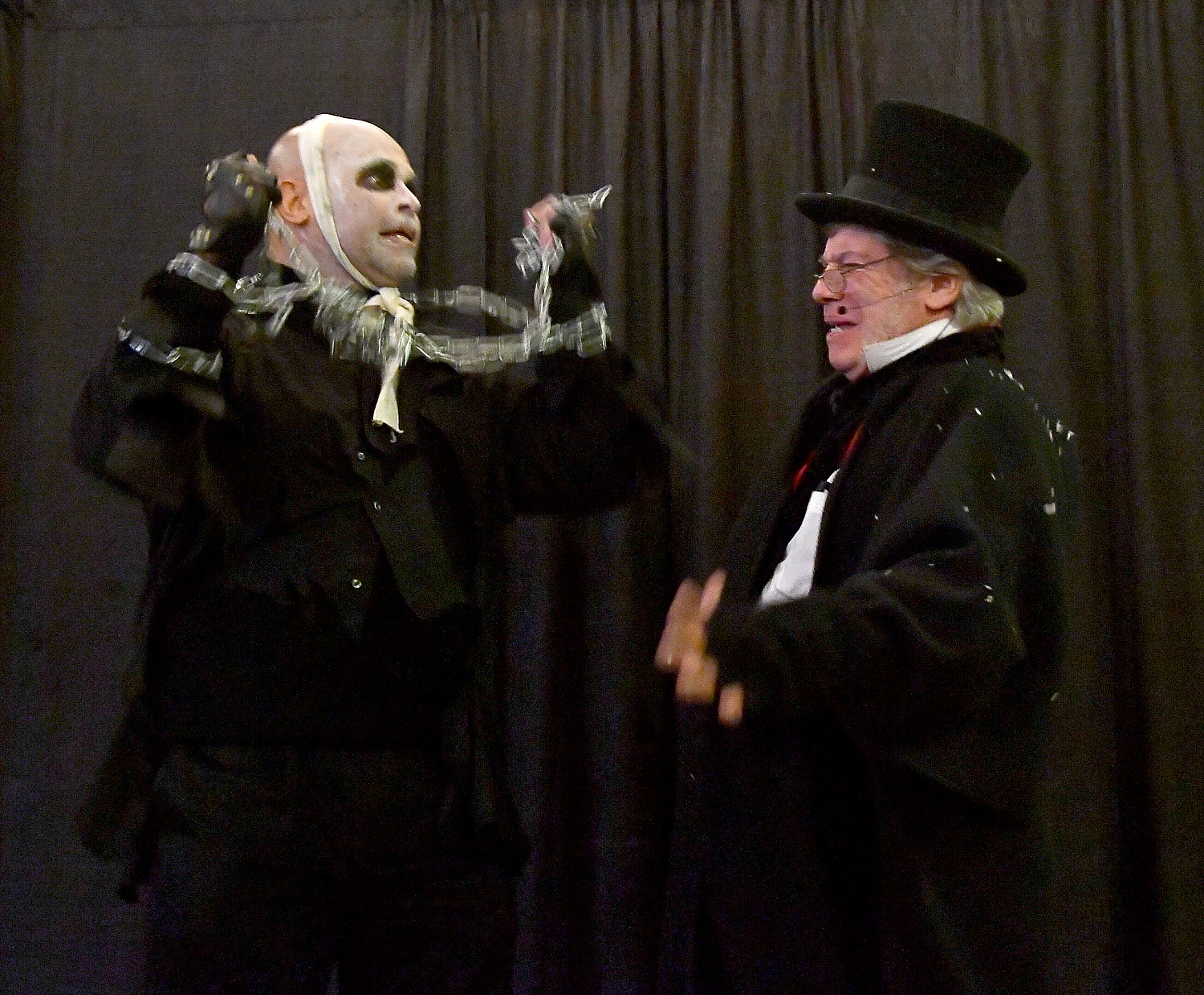

From here, I go back up to the court yard and find my way to Franklin’s print shop, where there is a replica of an old-style printing press (not much different from the days of Gutenberg), where National Park Rangers run off documents (you can buy a printed Declaration of Independence though Franklin never actually printed it). If you are lucky, you may visit when the ranger is in period dress.

On the Market Street side of Franklin Court, there is the B. Free Franklin Post Office, where you can get postcards hand-stamped just as one would have when Franklin was the first postmaster. The line of attached buildings are very much the way they were when Franklin lived here. You notice on Market Street and then around the historic district townhouses that still have the reliefs that show what fire insurance company protected the house. On this day, the street is closed off for a street festival. After spending some time enjoying the music and festivities.

I also pass a firehouse with a wonderful bust of Benjamin Franklin.

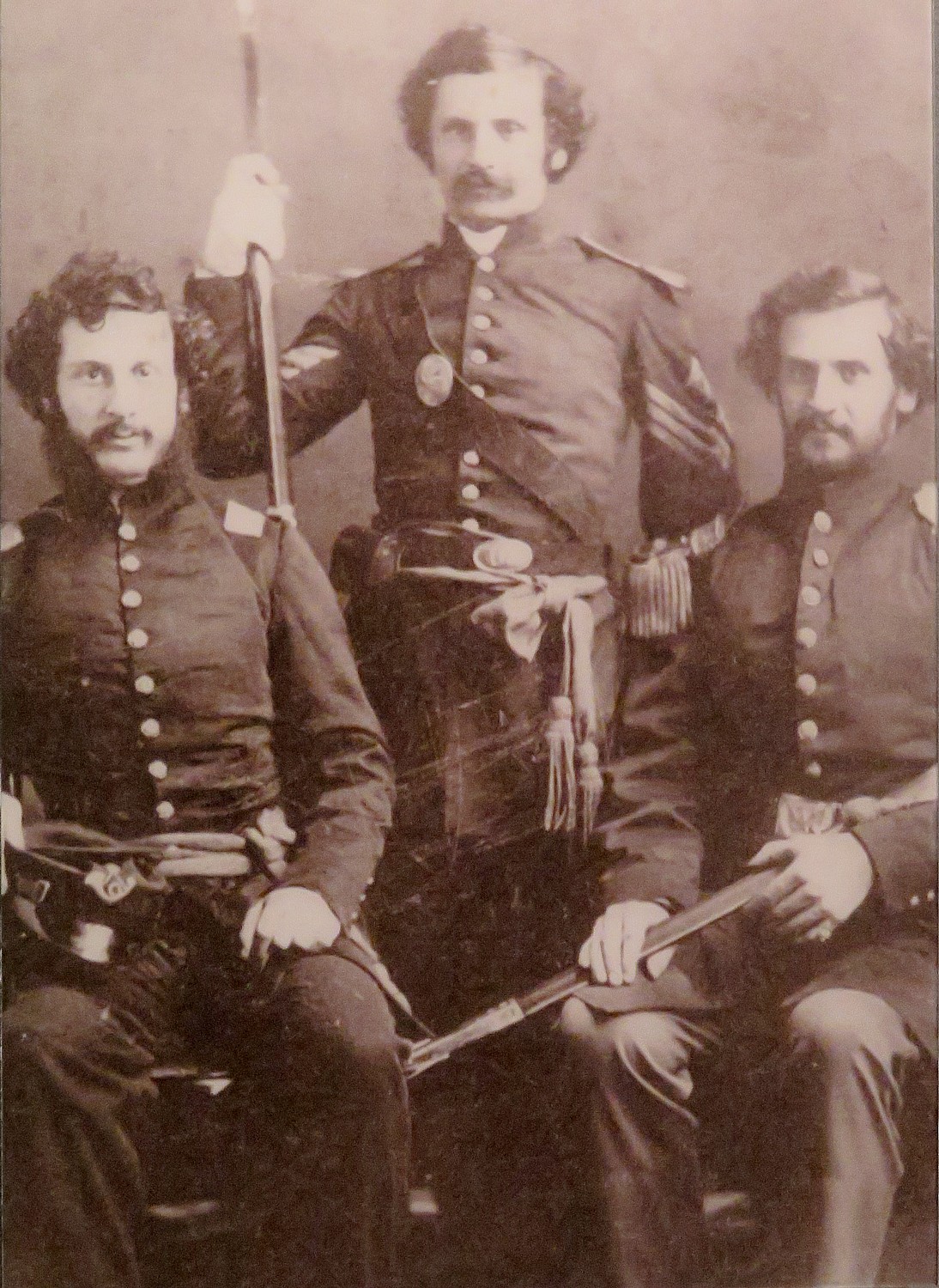

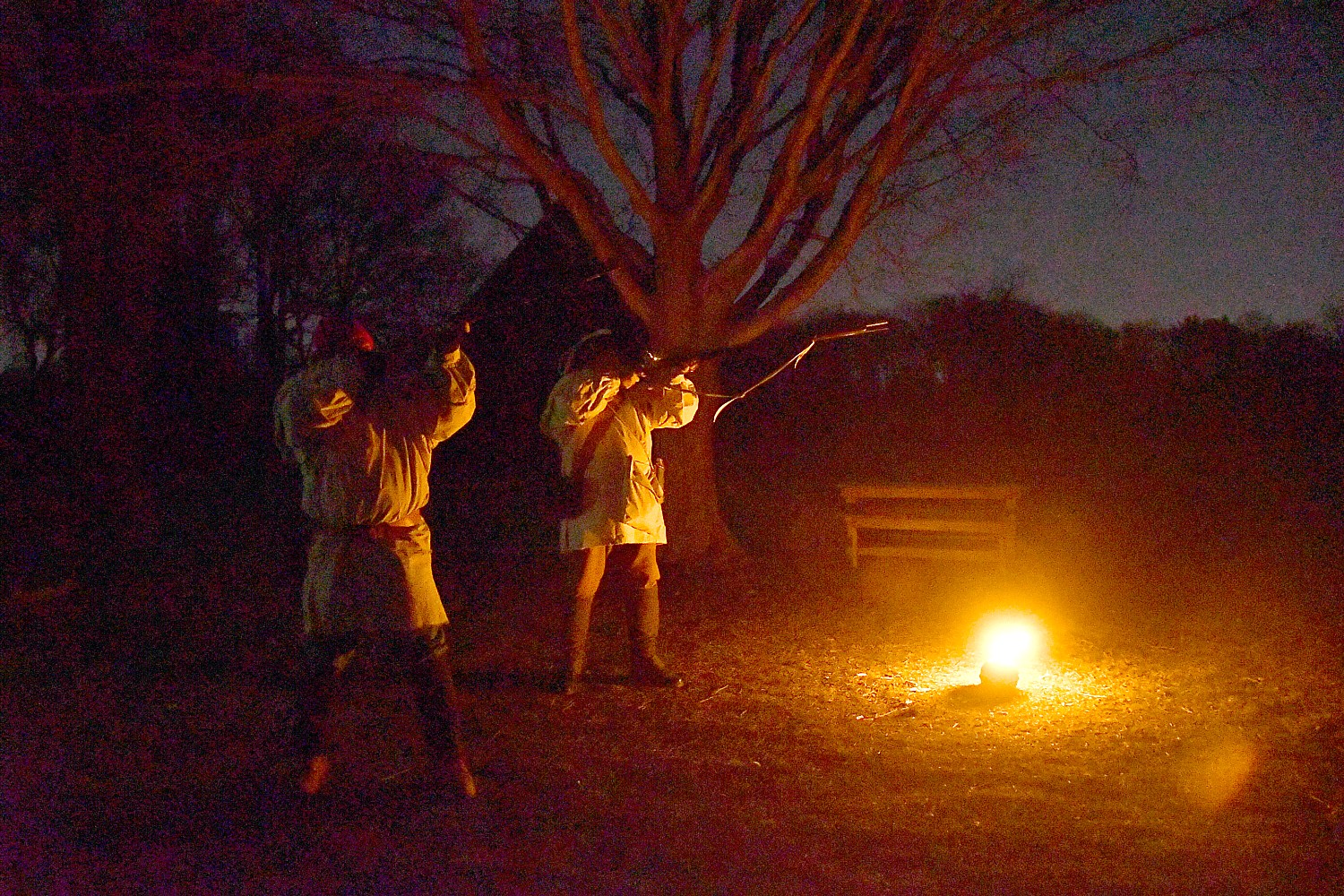

Philadelphia had just held a Veterans Day parade, and just as I pass the Christ Church Burial Ground where Benjamin Franklin and many other Founders are buried, I come upon Civil War re-enactors from the 3rd Regiment: Sgt Major Joseph Lee and Corporal Robert F. Houston.

The Franklins’ tombstones – extremely modest – is easily the most visited (and can be seen through the gate from the sidewalk). People throw pennies onto the tombstone – a nod to Franklin’s motto that “a penny saved is a penny earned,” as well as a symbol of good luck.

Others buried here include John Dunlap, who printed the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, composer and poet Francis Hopkinson and medical pioneers Dr. Benjamin Rush and Dr. Philip Syng Physick. Divided into quadrants, the ground is mapped and plots are identified with markers where the original inscriptions are gone. A book of 50 biographies is available for purchase at Christ Church. (There is an admission to the burial ground, $3 adults/$1 child or $8/$3 with guided tour.) (5th and Arch Streets, Philadelphia 19106, 215-922-1695, ext 30, http://www.christchurchphila.org/about-the-burial-grounds/

I walk the few blocks to the Betsy Ross House, another Revolutionary character who would have been thoroughly at home in the 21st Century.

Follow in Franklin’s Footsteps

VisitPhilly.org, the city’s convention and visitor bureau, offers a marvelous walking tour to discover historic attractions visited by Franklin himself, sites dedicated to his accomplishments and local restaurants that would appeal to one of history’s most prolific men.

The Franklin’s Footsteps Itinerary starts at the Benjamin Franklin Museum, Franklin Court, the Ghost House, the Print Shop and Post Office and continues:

City Tavern (138 S. 2nd St. 215-413-1443), where Colonial America is recreated at this authentic tavern in Old City

Carpenters’ Hall (320 Chestnut St., 215-925-0167), the site of the First Continental Congress, was once the home of Franklin’s Library Company and the American Philosophical Society (APS), two organizations he founded.

Christ Church (20 N. American St., 215-922-1695), where Franklin and his family attended services, and Christ Church Burial Ground.

Fireman’s Hall Museum, (147 N. 2nd St., 215-923-1438), commemorates the history of firefighting in an old firehouse

The Liberty Bell Center (6th & Market, 215-965-2305), home of the internationally known symbol of freedom (pick up timed tickets for Independence Hall at the Independence Visitor Center, or order them online at recreation.gov).

My immersion into Revolutionary War Americana in Philadelphia, which started with the National Museum of Jewish American History and Museum of American Revolution, continues at Betsy Ross House and the National Constitution Center.

Visit Philadelphia provides excellent trip planning tools, including hotel packages, itineraries, events listings: 30 S 17th Street, Philadelphia PA 19103, 215-599-0776, visitphilly.com.

See also:

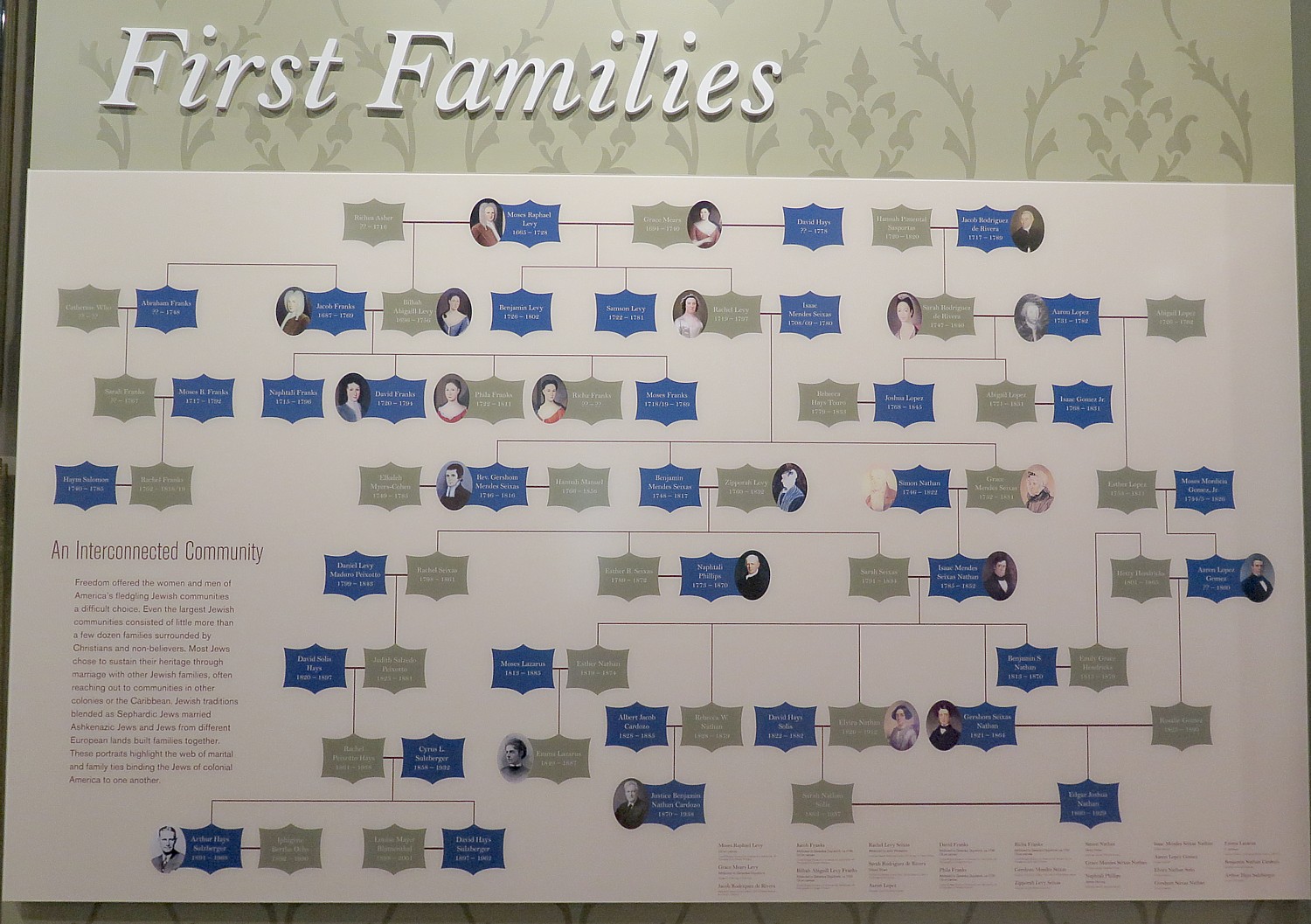

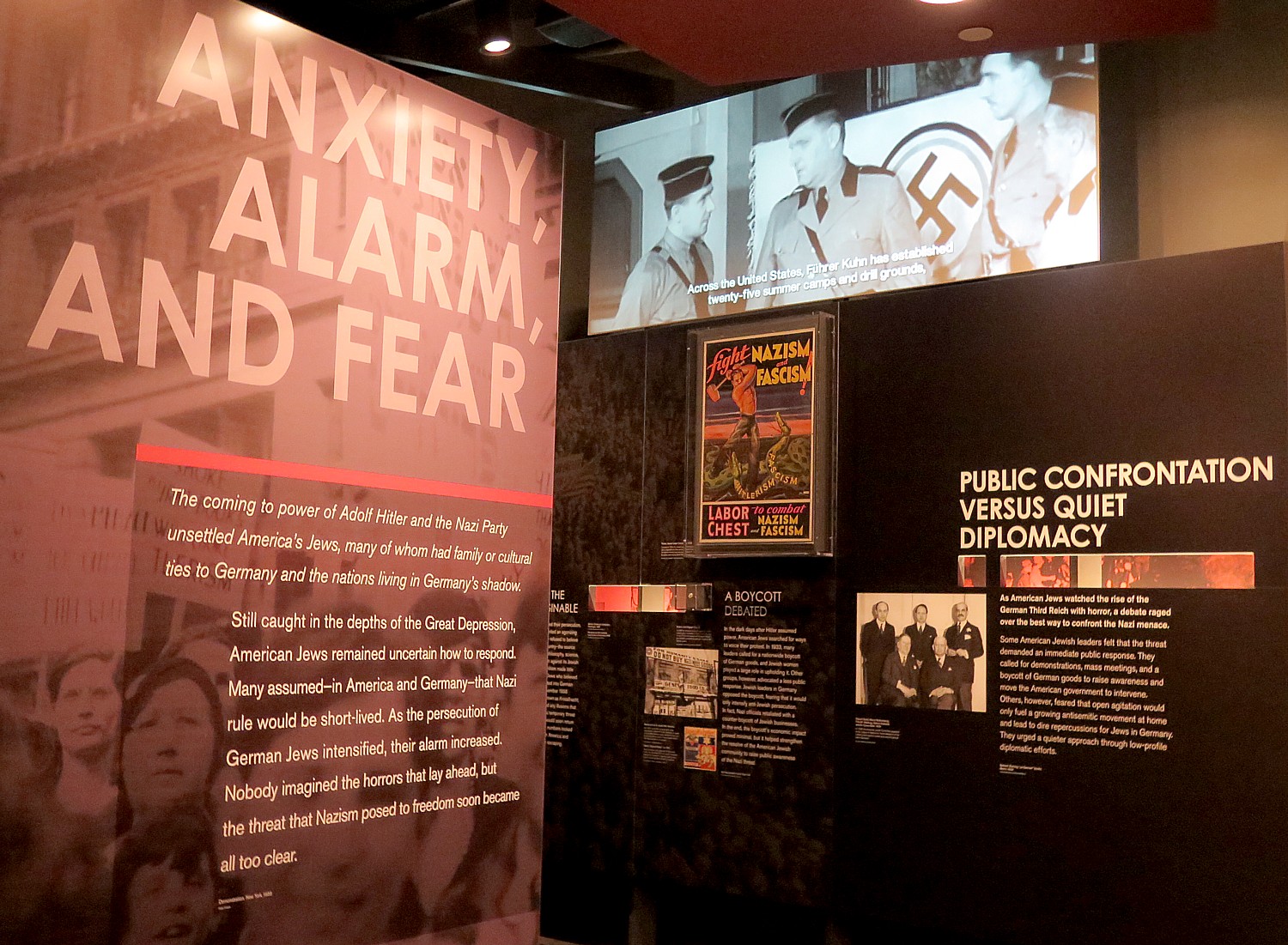

National Museum of American Jewish History is Unexpected Revelation in Philadelphia

Philadelphia’s New Museum Immerses You into Drama of America’s Revolutionary War

_____________________________

© 2018 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin , and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures