By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

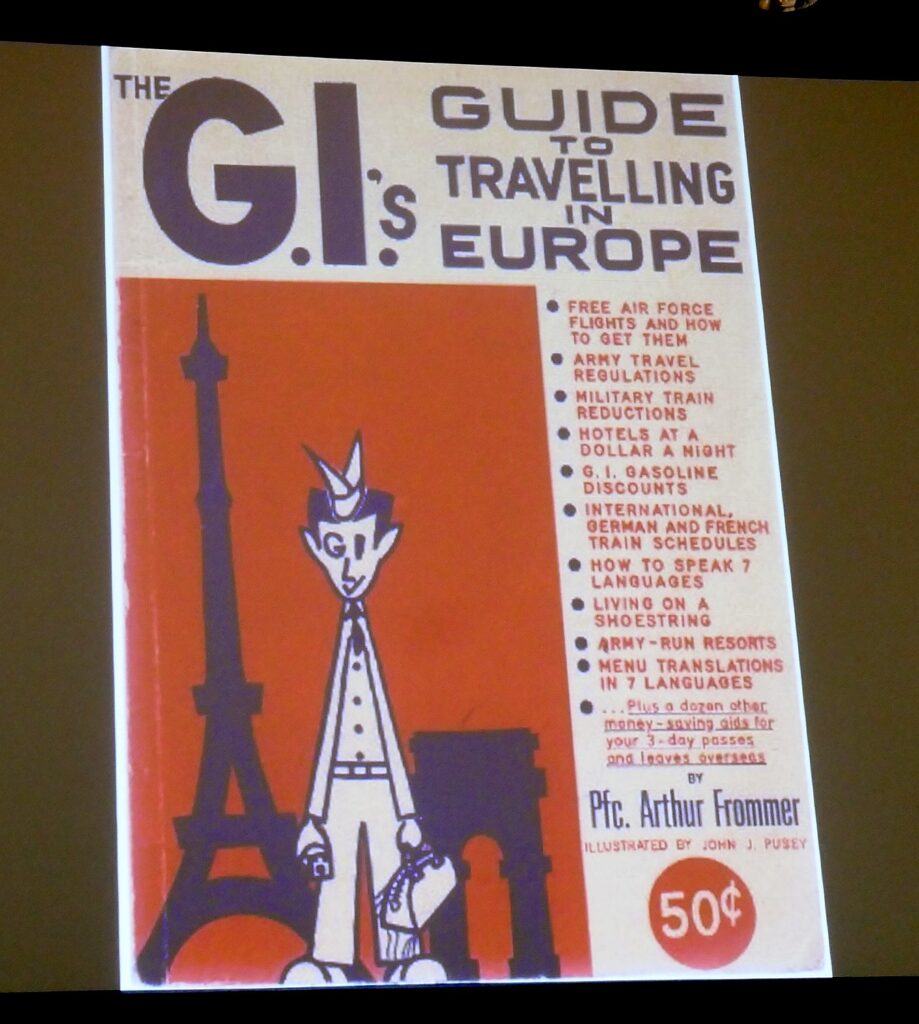

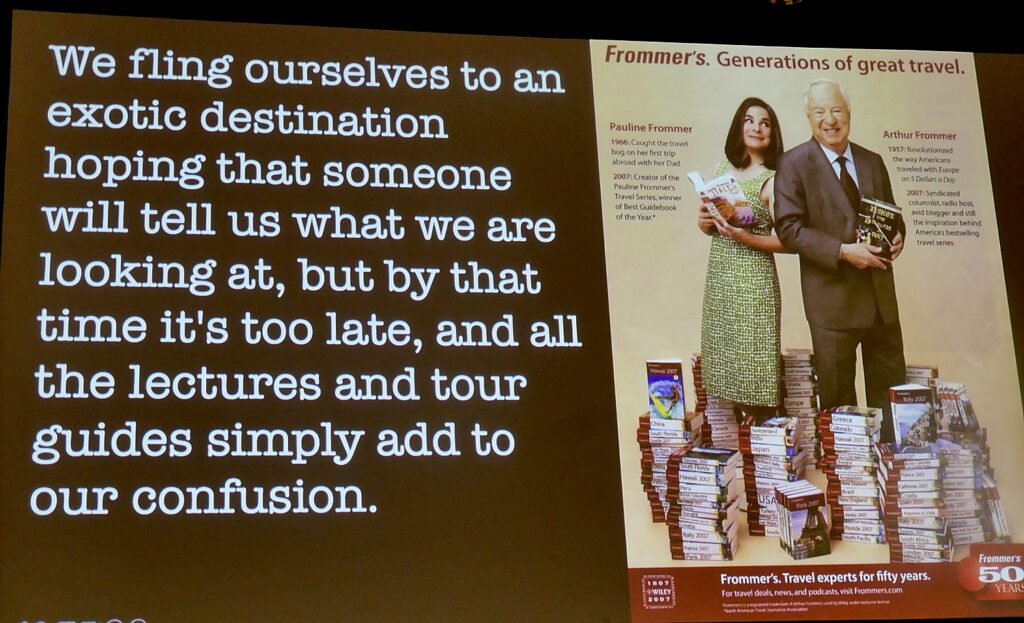

This year’s travel talk by Pauline Frommer at the New York Travel Show was a homage to her father, the legendary Arthur Frommer who single-handedly inspired generations of travelers not born into family fortune to experience the world, with his guidebooks, then radio and TV shows, starting with the iconic “Europe on $5 a Day”. His philosophy, mission and love of travel that infuse the Frommer guides have remained. He passed away in November.

At her talk, titled “Travel Lessons I’ve Learned From My Father That Will Make Your Next Vacation Less Expensive and More Meaningful,” she said, “He believed money should be used smartly. He believed travel could be a life-changing activity.”

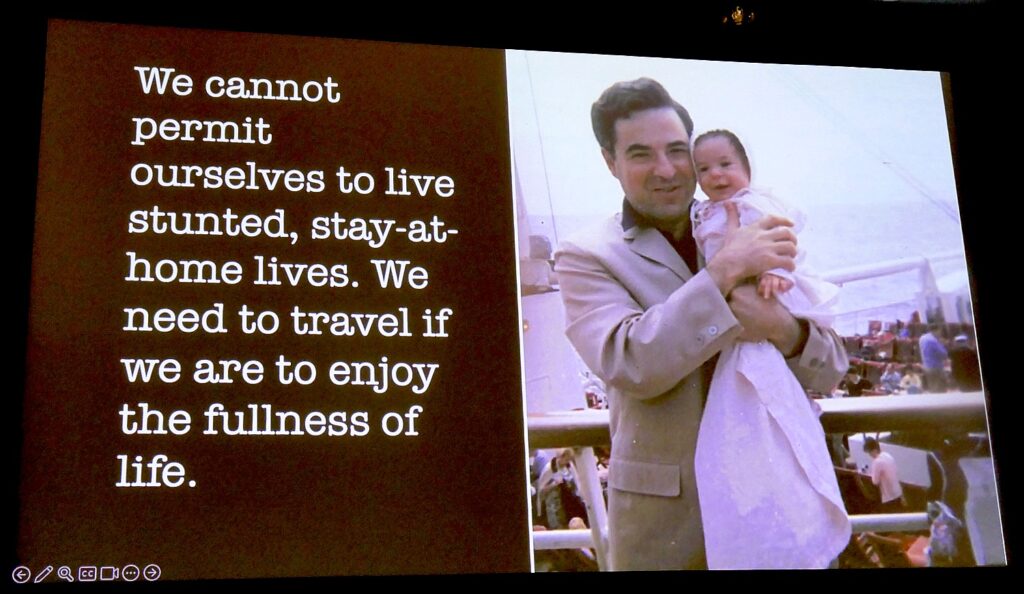

Quoting Arthur, she said, “We cannot permit ourselves to live stunted, stay- at-home lives. We need to travel if we are to enjoy the fullness of life… Contact with the new and the different is how we grow and develop. That may be possible in other ways than travel, but there is something about experiencing the world that cannot be duplicated… Nothing has the lasting impact of being there.”

Arthur Frommer devoted his life to guiding people how to travel inexpensively and how to have meaningful vacations, that shift who you are as a person in important

In 1957, when Arthur set out on his mission to inspire Americans to travel abroad, Americans – even middle class ones – were rich compared to rest of world – Europe was in rubble while Americans had dollars.

“Now we are in the same position – currently the Euro is almost equal to the $1: $1.02 to 1e (in 2016 it was $1.36 to 1e. The Japanese yen has never been this weak, 156 yen to $1; the dollar is worth 1.44 Canadian and the Mexican peso is at 20.78. It has never been so good.”

On the other hand many travel companies are using AI to raise prices surgically, depending upon your prior buying habits – what Joe Biden’s Federal Trade Commission called “surveillance pricing.” (Biden’s FTC also went after airlines, others for junk fees, requiring rapid cash refunds, cybertheft and greedflation, during his pro-consumer administration.)

“Middle men watch what consumers are doing, creating profiles of the consumer so they can tell different industries how much to charge, individually.

Delta Airlines’ CEO, on an earnings call, boasted how the airline was profiling, using AI to float the maximum airfare passengers would pay.

Have you had the experience of searching for an airfare, finding one, but going off to think about it for awhile, only to return and find the fare $50 higher? “That’s because you are being watched; the amount of surveillance is insane.”

Frommer’s antidote? “When searching for travel goods and services, be private – hide your identity. For example, subscribe to a VPN (virtual private network) to hide who you are; clear your cache and cookies. Use a different computer.

The best search engines for airfares, she recommends, are Momondo.com (owned and managed by Kayak.com) and Skyscanner.com.

But, she adds, “Then you don’t buy on them. There are so many issues in air travel, if you buy from a third party like an OTA [an online travel agent], you are last in line if something goes wrong. Search on the website, then buy from the airline.”

(Travel expert Peter Greenberg, at his talk at the travel show, adds that the OTAs always say there are only one or two seats available at that great price, but that is because the airline has only released that number of seats. He also advises searching online then booking directly with the airline.)

There are also days that are best to purchase air fares: Frommer recommends purchasing an airfare on Sunday can yield 6% savings on domestic fare, 17% savings on international.

Also, “buy 1-3 months out for domestic travel (for a 25% savings), 18-29 days out for international (for a 10% savings). Last year, it was 4 months out, but she acknowledges, “it takes courage to book so close.”

You get the best fares if you start your trip on a Thursday or Saturday (16% savings over flying on a Sunday), she says. “Sunday is the most expensive day to start a trip.”

Also, given the “chaos in the sky” with the doubling of cancellations in 2024, she recommends, “fly before 3 pm, or up the risk of being cancelled or delayed by 50%.” If you fly after 9 pm, your risk of being delayed or cancelled goes up by 57%. Fly after 9 pm and your risk of being delayed or cancelled goes up 57%

To get the best rate for a hotel, Frommer suggests booking three-plus months in advance for resorts, but just one week before in business-travel cities.

“Always get a reservation you can cancel.” (I have had great success finding hotels at hotels.com and booking.com, that provide great tools for location, amenities, nearby attractions, easy cancellation, and helpful reviews.)

Vacation home rentals, such as through airbnb.com may not be cheaper than hotels because of housekeeping fees and taxes (unless you are a family or couples traveling together), but typically afford more space, the convenience of kitchen and laundry, and are typically in neighborhoods so you get to connect with local people.

Looking for added value in accommodations? Consider hostels: “There are wonderful hostels all around the world, where you get private rooms, private bathrooms for much less than a hotel. There usually is a common area, a place where you can cook your own meal, do your laundry.”

“Typically there are also opportunities to meet and socialize with other travelers,” she said (as I found in Quito, Ecuador, where I was invited to a communal dinner). A good source for finding hostels is HostelWorld.com.

To find a tour, Frommer recommends: travelstride.com and tourradar.com, which are marketplace sites for tours. You put in dates and where you want to go and then can compare prices, highlights, what is offered. “Often the cheaper tours are by local tour operators that don’t have an international profile but go to same places, and often stay in the same hotels and restaurants.”

Travel insurance is recommended when you are taking a long-distance, expensive tour and want protection against cancellation (but read the fine print); but what you may well want when traveling abroad is medical insurance, covering evacuation if necessary. (Medicare isn’t applicable abroad.)

You can search for the policy that works best for your purpose at:

“Put in details and it generates a list. Inevitably the best is not the most expensive, usually it is in the middle cost range. No travel insurance company is always the best.” Also, she advises, “Never buy insurance through the travel provider.”

(Recently, in preparation for Discovery Bicycle Tours’ trip to Cambodia and Vietnam, I did the search at travelinsurance.com and found the policy that best fit my needs for medical coverage was through Generali Global Assistance.)

Every year, the Frommers offer their recommendations for where to go in the coming year. The hallmarks of the list have become finding the less crowded destinations worth a visit. (See the full article frommers.com/bestplaces2025)

Crete in Greece: it is one of the least crowded of the Greek islands because it is the largest- twice size of Rhode Island, while most travelers go to Mykonos or Santorini. “Santorini got 3 million visitors in 2024 – it was so hairy on the roads, the government asked the Santorini citizens to stay off the roads at certain hours because of the traffic jams with tour buses.” But Crete is the land of “Zorba the Greek”. “It is the most Greek of Greek islands, once part of the Venetian Empire, it looks like Venice and has incredible ancient ruins from when it was the center of the Minoan civilization – think Minator and Labyrinth.”

Looking to do an African safari? A safari in Zambia, famous for Victoria Falls , one of tallest in world, is as much as 25% less costly than Tanzania or Kenya. “They have all the animals – giraffes, elephants, hippos, lions – and also have a progressive system where the rangers who stop poaching are women. It is also one of the safest countries in Africa. Support them.”

Greenland is top of mind lately. “Bizarrely, Greenland just expanded its airport, so for the first time, can accommodate large jets. For the first time, you can go to this ice-covered nation direct from New York in the time it takes to go to Iceland. 80% of Greenland is covered by ice – you can do heli-skiing, snowshoeing, glacier cruises, see polar bears.: Frommer is anticipating Greenland will be the next Iceland. “Go before it’s too crowded. It’s a great adventure destination.”

The Caribbean country of Barbuda (part of Antigua and Barbuda) is an undeveloped, beautiful, pristine island (because it never had a big airport) that made the news 40 years ago when Princess Diana visited, thinking she could escape the paparazzi. “During WWII, allied generals were worried Germans would use the Caribbean islands as bases to invade the US – so built airports on Jamaica, Aruba, Puerto Rico and several other islands; after the war, they drew tourists. Barbuda is finally getting an international airport and Robert De Niro is building a resort on Barbuda, she said. “See it while it is in its more pristine state.”

Bath and Hampshire, England are “going crazy” this year over the 250th birthday of novelist Jane Austin (“Pride and Prejudice”, “Sense & Sensibility”) – there are Empire-style costumes you can rent, special exhibits. Bath also has one of England’s most important Roman ruins.

Tucson, Arizona is turning 250 years old this year, as well, and mounting celebrations all year long. Also, Tucson is the only city in the United States that is part of the Dark Sky program. On the edge of the city, Saguaro National Park, there is a free observatory you can go at night to look at stars with astronomers. Tucson is also the place for foodies, with a 4000-year old culinary tradition. “The United Nations named it the only culinary UNESCO World Heritage site in the US. There are all the different influences in the food. There are all kinds of food celebrations for the 250th.

“My father said, ‘Don’t just go to dead sites.’ If I had never traveled, I would never have understood that all people, no matter how exotic their appearance, have basically the same concerns, the same desires. Don’t just go to see things, but meet people.”

To meet people when you travel:

The International Greeter Association connects you to people who love their home communities and give free tours. You can go to Tokyo and find a greeter to take you around Tokyo for a day, teach you how to use subway, show you a neighborhood, free.” In Chicago, Frommer took a tour of downtown to discover public art. She toured a Hispanic neighborhood in the Bronx, visiting stores and apartment buildings, to “learn about another side of New York City.”

Find other free tours led by locals through the International Greeter Association, a worldwide nonprofit organization offering private free walks with locals through some 400 cities in 60 countries. https://internationalgreeter.org). Also, GetYourGuide.com.

(Athens, Greece has a program through the tourist office, “This is My Athens,” that sets you up with a local to show you around for free, https://www.thisisathens.org/withalocal/. We have also found free walking tour programs in most cities by googling, such as in Quito, freewalkingtourecuador,com, where you just tip the guide after. )

Airbnb.com Experiences provides links to little companies with people with experiences to share. Frommer related taking her 15-year old daughter on a tour of Paris consignment stores with a fashion expert. “We have been to Paris many times but saw things never had.”

TravelingSpoon.com and EatWith.com link travelers to culinary experiences with local people, the best local cooks in different communities, home cooks. Frommer described such an experience with an “Italian nona,” whose grandson translated as she prepared the meal in her kitchen. “We all gathered for a meal. It cost as much as a high end restaurant, but it was our most memorable meal in Italy that time.”

Another way to have an extraordinary experience is to do short-term work in a foreign destination– something that is particularly appealing for young people taking a gap year – which do not require work visas. Opportunities can be found at:

WWOOF.org (Willing Workers on Organic Farms)

The heyday for digital nomads may be passed, but to find what remains, you might consult:

Travelers are increasingly concerned about sustainability and traveling responsibly, so the benefits of their visit (providing economic foundation to sustain people living in their community, maintaining culture and heritage and sites) do not outweigh the negatives of overtourism.

Tour operators, like Intrepid Travel (intrepidtravel.com) are taking this into account in designing itineraries so they are more hub-and-spoke and less travel by bus or airline; several, like G Adventures (gadventures.com) are conscious to purchase local products and hire locals, as well as contribute a portion of the tour price to benefit the community; Seacology (seacology.org), takes you to places threatened by ocean rise then donate money back to community.

“At its best, travel should challenge our preconceptions and most cherished views, cause us to rethink our assumptions, shake us a bit, make us broader minded and more understanding,” Frommer said.

Her father, Arthur Frommer, “changed this industry in powerful ways, democratized travel. He was one of the first to say average people should travel, not just the wealthy, elite. Travel afforded the opportunity to expand your life, expand your mind, and do it in a way that pushes the cause of world peace. He truly believed that when we get to know other countries, wonder at the beauty of them, we won’t attack or invade, and our hearts will break when things go wrong there.”

__________________

© 2025 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Bluesky: @newsphotosfeatures.bsky.social X: @TravelFeatures Threads: @news_and_photo_features ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures