by Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

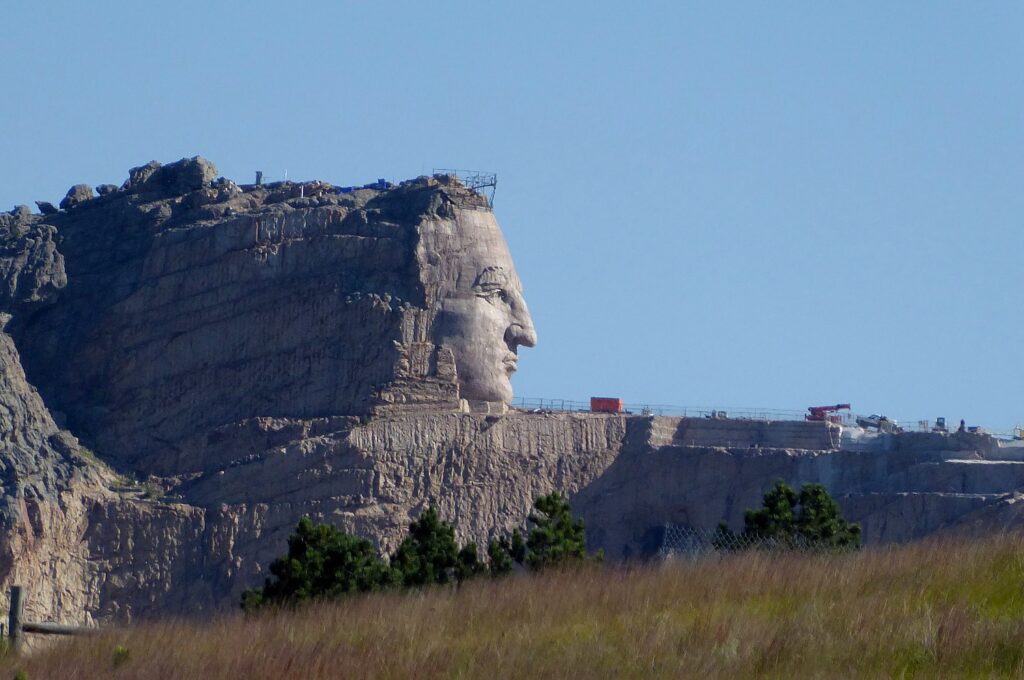

The Crazy Horse Memorial is sensational, awesome and profound. The carved portrait in the cliff-side, which I first encounter by surprise as I bike on the Mickelson Trail between Custer and Hill City is spectacular enough, but there is so much more to discover. There is also a superb Museum of Native Americans of North America (it rivals the Smithsonian’s Museum in Washington DC) where you watch a terrific video that tells the story of the America’s indigenous people, and can visit the studio/home of the sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski. It is the highlight of our third day of the Wilderness Voyageurs “Badlands and Mickelson Trail” bike tour of South Dakota.

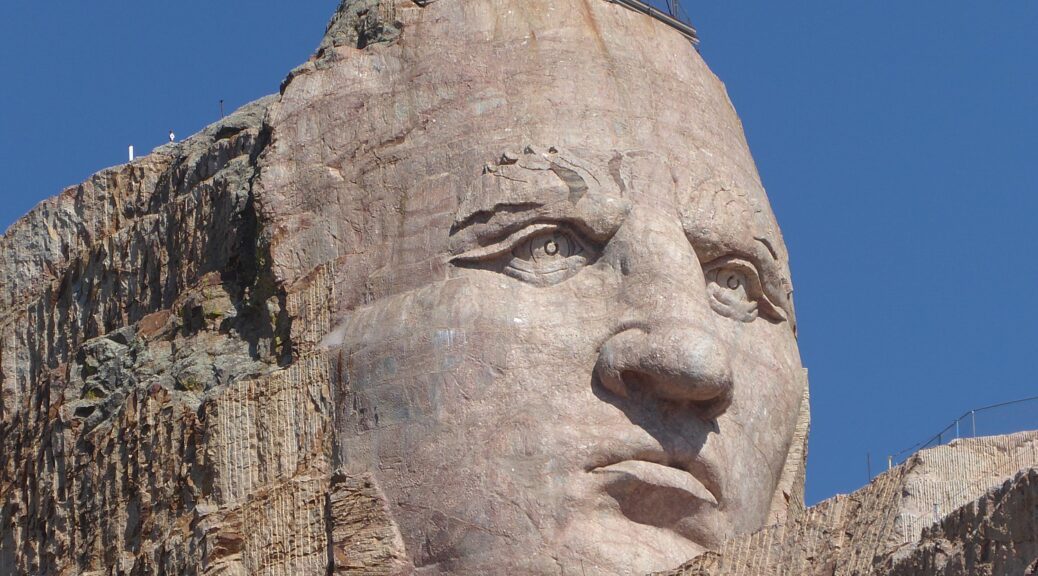

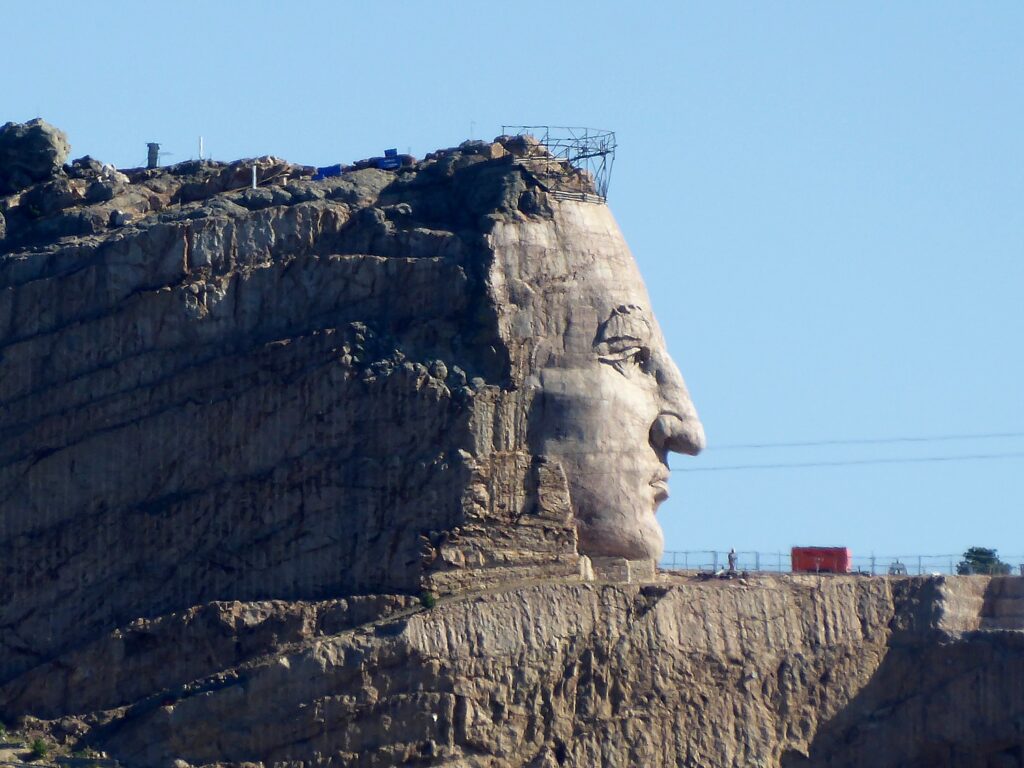

I rush to join a tour (a modest extra fee) that brings us right to the base of the sculpture. You look into this extraordinary, strong face – some quartz on the cheek has a glint that suggests a tear.

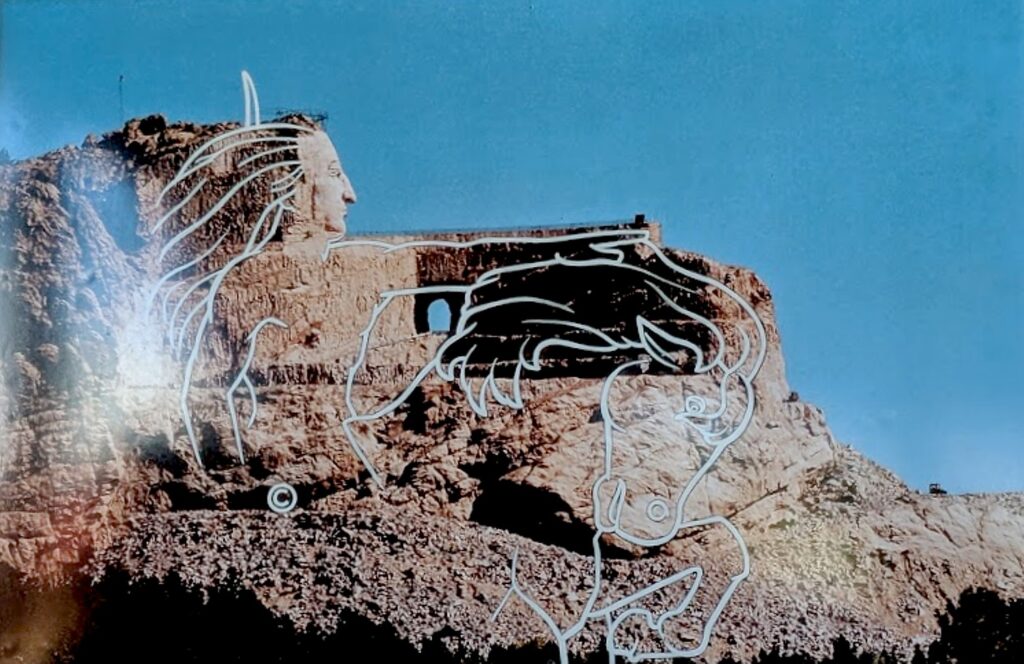

Only then do I realize that, much to my surprise, seeing the scaffolding and equipment, that 70 years after sculptor Ziolkowski started carving the monument in 1947, his grandson is leading a crew to continue carving. Right now it is mainly a bust – albeit the largest stone carving in the world – but as we see in the museum, the completed sculpture will show Crazy Horse astride a horse, his arm outstretched toward the lands that were taken from the Lakota.

At 87 ft 6 inches high, the Crazy Horse Memorial is the world’s largest mountain carving in progress. They are now working on the 29-foot high horse’s head, the 263-foot long arm, and 33 ft-high hand, the guide tells us. The horse’s head will be as tall as 22-story building, one-third larger than any of the President’s at Mount Rushmore. The next phase of progress on the Mountain involves carving Crazy Horse’s left hand, left forearm, right shoulder, hairline, and part of the horse’s mane and head over 10-15 years. The plan is to carve the back side of the rock face as well, which would make the Crazy Horse Memorial a three-sided monument.

When completed, the Crazy Horse Mountain carving will be the world’s largest sculpture, measuring 563 feet high by 641 feet long, carved in the round. The nine-story high face of Crazy Horse was completed on June 3, 1998; work began on the 22-story high horse’s head soon after.

“One if hardest decisions (after two years of planning) was to start with head, not the horse (in other words, work way down),” the guide tells us.

In 71 years of construction, there have been no deaths or life threatening injuries of the workers (though there was that accident when a guy driving a machine slipped off edge; his father told him he had to get the machine out himself.)

Four of Korczak and Ruth’s 10 children and three of his grandchildren still work at the Memorial.

On the bus ride back to the visitor center, the guide tells us that Zioklowski was a decorated World War II veteran who was wounded on D-Day, but was so devoted to the Crazy Horse Memorial, he even planned for his death: there is a tomb in a cave at the base of the monument..

Back at the visitor center/museum, the story about the Crazy Horse Memorial is told in an excellent film:

The overwhelming theme is to tell the story, to give a positive view of native culture, to show that Native Americans have their own heroes, and to restore and build a legacy that survived every attempt to blot it out in a form of genocide.

There were as many as 18 million Indians living in North America when the Europeans arrived (the current population is 7 million in the US). “These Black Hills are our Cathedral, our sacred land,” the film says.

Crazy Horse was an Ogala Lakota, born around 1840 on the edge of Black Hills. He was first called “Curly” but after proving himself in battle, earned his father’s name, “Crazy Horse” (as in “His Horse is Crazy”). The chief warned of encroaching “river” of settlers, leading to 23-years of Indian wars. In 1876 Crazy Horse led the battle against General Custer, the Battle of Little Big Horn (known as Custer’s Last Stand, but Indians call it “the Battle of Greasy Grass”). It was a victory for the Indians, but short-lived. Soon after, the US government rounded up the rebels and killed Crazy Horse while he was in custody at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. (See www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/crazy-horse.htm)

I am introduced to a new hero: Standing Bear.

Standing Bear was born 1874 near Pierre, South Dakota, and was among the first Indian children sent away to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania where his name was randomly changed to “Henry.” In the school, their Indian identity was forcibly removed – they cut the boys’ hair, they were not allowed to speak their language “to best help them learn the ways of non-native.”

“As a result of attending Carlisle, Standing Bear concluded that in order to best help his people, it would be necessary for him to learn the ways of the non-Native world. Somewhat ironically, Carlisle – an institution that was designed to assimilate Native Americans out of their indigenous ways – became a source of inspiration that Standing Bear would repeatedly draw upon to shape his enlightened understanding of cross-cultural relationships, as well as to find new ways of preserving his people’s culture and history.” He honed leadership skills like public speaking, reasoning, and writing, realizing that because of the changing times, the battle for cultural survival would no longer be waged with weapons, but with words and ideas. “This realization became a driving force behind much of his work during his adult life and led him to become a strong proponent of education,” the background material on the Crazy Horse Memorial website explains (crazyhorsememorial.org).

Standing Bear attended night school in Chicago while he worked for the Sears Roebuck Company to pay for his schooling. With feet firmly placed in both worlds, he became heavily involved in the affairs of his people over the course of his life and politically astute —working with Senator Francis Case and serving as a member of the South Dakota Indian Affairs Commission. He led the initiative to honor President Calvin Coolidge with a traditional name – “Leading Eagle,” taking the opportunity for advocacy during the naming ceremony to challenge President Coolidge to take up the leadership role that had been previously filled by highly-respected leaders such as Sitting Bull and Red Cloud.

In 1933, Standing Bear learned of a monument to be constructed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, to honor his maternal cousin, Crazy Horse, who was killed there in 1877. He wrote to the organizer that he and fellow Lakota leaders were promoting a carving of Crazy Horse in the sacred Paha Sapa – Black Hills.

Standing Bear looked for an artist with the skill to carve the memorial to his people that would show Indians had heroes too and turned to Korczak Ziolkowski, a self-taught sculptor who had assisted at Mount Rushmore and had gained recognition at the 1939 World’s Fair. Standing Bear invited him back to the Black Hills.

Born in Boston of Polish descent in 1908, Korczak was orphaned when he was one year old. He grew up in a series of foster homes and is said to have been badly mistreated. He gained skills in heavy construction helping his foster father.

On his own at 16, Korczak took odd jobs to put himself through Rindge Technical School in Cambridge, MA, after which he became an apprentice patternmaker in the shipyards on the rough Boston waterfront. He experimented with woodworking, making beautiful furniture. At age 18, he handcrafted a grandfather clock from 55 pieces of Santa Domingo mahogany. Although he never took a lesson in art or sculpture, he studied the masters and began creating plaster and clay studies. In 1932, he used a coal chisel to carve his first portrait, a marble tribute to Judge Frederick Pickering Cabot, the famous Boston juvenile judge who had befriended and encouraged the gifted boy and introduced him to the world of fine arts.

Moving to West Hartford, Conn., Korczak launched a successful studio career doing commissioned sculpture throughout New England, Boston, and New York.

Ziolkowski wanted to do something worthwhile with his sculpture, and made the Crazy Horse Memorial his life’s work.

“Crazy Horse has never been known to have signed a treaty or touched the pen,” Ziolkowski wrote. “Crazy Horse, as far as the scale model is concerned, is to be carved not so much as a lineal likeness, but more as a memorial to the spirit of Crazy Horse – to his people. With his left hand gesturing forward in response to the derisive question asked by a white man, ‘Where are your lands now?’ He replied, ‘My lands are where my dead lie buried’.”

There is no known photo of Crazy Horse, Ziolkowski created his likeness from oral descriptions.

He built a log studio home (which we can visit) at a time when there was nothing around – no roads, no water, no electricity. For the first seven years, he had to haul himself and his equipment, including a decompressor and 50 pound box of dynamite, up 741 steps.

Living completely isolated in the wilderness, Korczak and his wife Ruth bought an 1880s one-room school house, had it moved to this isolated property and hired a teacher for their 10 children.

There is so much to see here: The Museums of Crazy Horse Memorial feature exhibits and engaging experiences that let you discover Native history and contemporary life, the art and science of mountain carving and the lives of the Ziolkowski family.

THE INDIAN MUSEUM OF NORTH AMERICA® houses an enormous collection of art and artifacts reflecting the diverse histories and cultures of over 300 Native Nations. The Museum, designed to complement the story being told in stone on the Mountain, presents the lives of American Indians and preserves Native Culture for future generations. The Museum collection started with a single display donated in 1965 by Charles Eder, Hunkpapa Lakota, from Montana, which remains on display to this day. The Indian Museum has about the same number of annual visits as the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. Close to 90% of the art and artifacts have been donated by generous individuals, including many Native Americans.

The gorgeous building housing the Museum was designed and built by Korczak Ziolkowski and his family in the harsh winter of 1972-73, when no work was possible on the Mountain. The Museum incorporated Korczak’s love of wood and natural lighting, being constructed from ponderosa pine, harvested and milled at Crazy Horse Memorial. The original wing of the museum was dedicated on May 30, 1973. In the early 1980s, Korczak planned a new wing of the Museum to accommodate the growing collection of artifacts. He did not live to see his plans realized, instead his wife Ruth Ziolkowski and 7 of their children made sure the new wing was built. The structure was built in the winter of 1983-84 and funding came in large part from a $60,000 check left in the Crazy Horse Memorial contribution box in late August of 1983. The contributor said he was moved by the purpose of Crazy Horse, Korczak, and his family’s great progress and by the sculptor’s reliance on free enterprise and refusal to take federal funds

The Ziolkowski Family Life Collection is shown throughout the complex and demonstrates to people of all ages the timeless values of making a promise and keeping it, setting a goal and never giving up, working hard to overcome adversity, and devoting one’s life to something much larger than oneself. There are portraits of the couple and personal effects that tell their life’s story.

The Mountain Carving Gallery shares the amazing history of carving the Mountain. It features the tools Korczak used in the early years of carving, including a ½ size replica of “the bucket” – a wooden basket used with an aerial cable car run by an antique Chevy engine that allowed the sculptor to haul equipment and tools up the Mountain. Displayed in the Mountain Carving Room are the measuring models used to carve the face of Crazy Horse, plasters of Crazy Horse’s face and the detailed pictorial progression of carving the face. They also detail the next phase in the Memorial’s carving which is focused on Crazy Horse’s left hand and arm, the top of Crazy Horse’s head, his hairline, and the horse’s mane. If you stand in just the right spot, you can line up the model of how the finished work will look against the actual mountain sculpture as it is.

Crazy Horse Memorial is actually a private, nonprofit (they also have a nonprofit college and medical training center that educates Indians), and twice turned down federal funding because “they didn’t believe the government would do it right.” Indeed, Mount Rushmore (which we see on the last day of our bike tour) was never completed because the federal government stopped funding the project. The entrance fee ($30 per car, 3 or more people, $24 per car two people, $12 per person, $7 per bicycle or motorcycle) support the continued carving, the Indian Museum of North America and the Indian University of North America, which assists qualifying students get their college degrees.

Once again, I am so grateful that I am not being pushed along with an artificial time limit by the Wilderness Voyageurs guides, I wander through the vast complex trying to take it all in. I am utterly fascinated.

I buy postcards for 25c apiece and stamps, sit with a (free) cup of coffee in the cafe and mail them at their tiny post-office. There is an excellent gift shop.

The Crazy Horse Memorial is open 365 days of the year, with various seasonal offerings.

(Crazy Horse Memorial, 12151 Avenue of the Chiefs, Crazy Horse, SD, 605-673-4681, crazyhorsememorial.org.)

I’m the last one to leave the Crazy Horse Memorial, and note that the bike of our sweeper guide for today John Buehlhorn, is still on the rack, but I figure he will see that I have gone and catch up to me, so I get back on the Mickelson Trail. He catches me again when I don’t realize to get off the trail at Hill City, where we are on our own for lunch and exploring the town.

Hill City is really charming and the home of the South Dakota State Railroad Museum, where you can take a ride on an old-time steam railroad. The shops are really pleasant.

The Wilderness Voyageurs van is parked there in case anybody needs anything.

The ride to the Crazy Horse Memorial was uphill on the rail trail for 8 miles but going down hill isn’t a picnic because of the loose gravel – but not difficult and totally enjoyable. We ride through train tunnels and over trestles. It is no wonder that the 109-mile long Mickelson Trail, which is a centerpiece of the Wilderness Voyageurs’ tour, is one of 30 rail-trails to have been named to the Hall of Fame by Rails-to-Trails Conservancy. We finish this day’s ride at Mystic at the 74.7-mile marker– we’ll ride the remaining miles on another day. Mystic used to be a significant town when the railroad ran here. Now there are just two buildings and four residents.

I notice the sign tacked up at the shelter: Be Aware: Mountain Lions spotted on the trail toward Rochford within the last few days.

We are shuttled back to Custer for our second night’s stay at the Holiday Inn Express (very comfortable, with pool, game room, WiFi and breakfast), and treated to a marvelous dinner at one of the finer dining restaurants, the Sage Creek Grill (611 Mount Rushmore Road, Custer).

Wilderness Voyageurs started out as a rafting adventures company 50 years ago, but has developed into a wide-ranging outdoors company with an extensive catalog of biking, rafting, fishing and outdoor adventures throughout the US and even Cuba, many guided and self-guided bike itineraries built around rail trails like the Eric Canal in New York, Great Allegheny Passage in Pennsylvania, and Katy Trail in Missouri.

There are still a few spots left on Wilderness Voyageurs’ Quintessential West Cuba Bike Tour departing on March 21.

Wilderness Voyageurs, 103 Garrett St., Ohiopyle, PA 15470, 800-272-4141, bike@Wilderness-Voyageurs.com, Wilderness-Voyageurs.com.

_________________________© 2020 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visitgoingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions toFamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures