by Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

Saigon is the second leg of nine during a 23-day, around-the-world Global Scavenger Hunt, “A Blind Date with the World,” where we don’t know where we are going until we are given 4-hour notice. Under the Global Scavenger Hunt rules, you are not allowed to use a phone or computer for information or reservations, hire a private guide, or even use a taxi for more than 2 scavenges at a time, since the object is to force you to interact with locals. Though we were not officially competing for “World’s Best Travelers,” my teammate, Margo (who I only met on this trip) and I basically followed the rules in Vancouver and during our first day in Vietnam, but we had to deviate on the second day.

It is shortly before 4 pm in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), Vietnam, by the time we have received our book of scavenges from Bill Chalmers, the Global Scavenger Hunt ringmaster (as he likes to be called), who has ranked Vietnam a “Par 3” in difficulty (on a scale of 1-6), strategized what scavenges we will undertake, and after a swim in the hotel’s pool (so hot even the pool was like a bathtub), we head out of the Majestic Hotel, a five-star historic property, toward Ben Thank Market, one of the scavenges on the list.

Built in 1870 by the French who colonized Vietnam for 100 years, it is where then and now, you can find locals and tourists alike, with row after row after row chock-a-block full of almost everything imaginable. (Be prepared to bargain aggressively; the shopkeepers are even more aggressive). I come away with a few things I can’t bear to pass up, when Margo realizes a second scavenge we can accomplish: tasting three separate fruits (there is heavy emphasis on “experience” scavenges that involve food, and Vietnam, Bill says, is one of the great food places in the world).

We find a fruit stand and sure enough, there are fruits I have never seen before, including one, called dragon fruit, which looks like it was divined by JK Rowling for Harry Potter; the others we sample: rambutan, mangosteen, longan. We are standing around these ladies, asking them to cut open the various fruits so we can sample them to complete the scavenge, taking the photos we need to document.

Among the other scavenges on the list here in the market: to find a cobra in jar of alcohol; the tackiest souvenir in market; and a wet market (which befuddles most of us and turns out to be the meat market which is hosed down).

We ask locals for directions to our next stop: the Water Puppet Show of Vietnam at the Golden Dragon Water Puppet Theater. It seems walkable but we get lost along the way (technically we can’t use the GPS on the phone, but we aren’t competing – we still get lost) and are simply amazed at the rush and crush of mopeds (mainly) and cars in this city of 9 million where there are an estimated 7 million scooters, and the range of what people carry on them without a second thought. I literally stand in a traffic island to get the full view.

We are also amazed we are able to function having departed Vancouver, Canada, for Vietnam at 2 am for a 14-hour flight to Taipei, followed by an hour lag time before a 3-hour connection to Saigon. Time has become a very fluid, meta thing.

But we forge on (the secret to avoiding being taken down by jet lag is to stay up until bedtime). This is also on the scavenger list and as it turns out, we meet several other teams from our group.

The performance proves fabulous and unexpected – the puppets actually emerge out of water; water is their platform. There is musical accompaniment on traditional instruments and the musicians also become the characters and narrators and sing. This is quite an outstanding cultural performance – the artistry and imaginativeness of the puppets (who swim, fish, plant rice which then grows, race boats, dance, catch frogs and do all sorts of things with incredible choreographed precision, is incredible.

These seem to be folk stories, and the music is traditional. It doesn’t matter if you don’t understand Vietnamese. It confounds me how they do such precise choreography from the water (the puppeteers are behind a gauze curtain; controlling with bubble wands horizontally). The artistry is magnificent and the experience an utter delight. (Golden Dragon Water Puppet Theatre, 558 Ngyuyen Thi Minh Kahi Street, Dist.1, HCMC, www.goldendragonwaterpuppet.com).

From there, we take a taxi to hit another scavenge, going to the Saigon Skydeck on the 49th floor of the Bitesco Financial Tower, which affords beautiful scenes of Saigon. From here, all you see is a very modern city. Many of the buildings below are decorated in colored lights. This is an example of modern Saigon that is rising. (Skydeck senior rate $5; some places have senor rates, others don’t, so ask)

Back at the Hotel Majestic, we go up to the 8th floor M Club, a delightful rooftop bar, where there is a band playing. The open-air views of the Saigon River and the skyline are just magnificent. Margo orders a “Majestic 1925” which is Bourbon, infused orange, sweet vermouth, Campari, orange bitter, orange zest, and smoked – the whole process done on a table brought to us, as a crowd gathers to watch the mixocologist light a torch to generate the smoke. Quite a scene.

Day 2 in Vietnam: Confronting the Horrors of War

Whereas my first afternoon and evening in Ho Chi Minh City was devoted to seeing the city as it is today – albeit dotted with centuries old buildings, markets and heritage – the second day is a somber, soul-searching journey back in time. Indeed, as I wander around the city, you don’t see any obvious scars of the Vietnam War.

One of the signature sights of a visit to Ho Chi Minh City is the Cu Chi Tunnels. My teammate Margo has already been there and doesn’t want to return, but I feel duty-bound to see it for myself. I wake up early and go down to the hotel concierge to see if I can get on the 7:30 am half-day trip to the Cu Chi Tunnels.

The concierge calls the tour company and says there is room on the bus and that they pick up right at the hotel. I am off. (545,000 Dong, about $25, www.saigontourist.net, www.e-travelvietnam.com)

As we travel outside through the city, the guide points out sights and gives us a history of Vietnam, going back to the Chinese who came in the 1600s, the French who came later, the Vietnam War and the aftermath, while hardly disguising resentment of the North Vietnamese who have flooded into the city since the war. Ho Chi Minh City has grown from a city of 2 million to 9 million today, with 7 million scooters (here, instead of Uber car, you summon a Grab scooter).

It’s an opportunity to see more of the city and soon we are in the countryside, traveling through small villages and farms where we see cemeteries, markets, houses, a few animals, rubber plantations. We see new agricultural techniques being used on farms and pass an agricultural research center. It is about an hour’s drive.

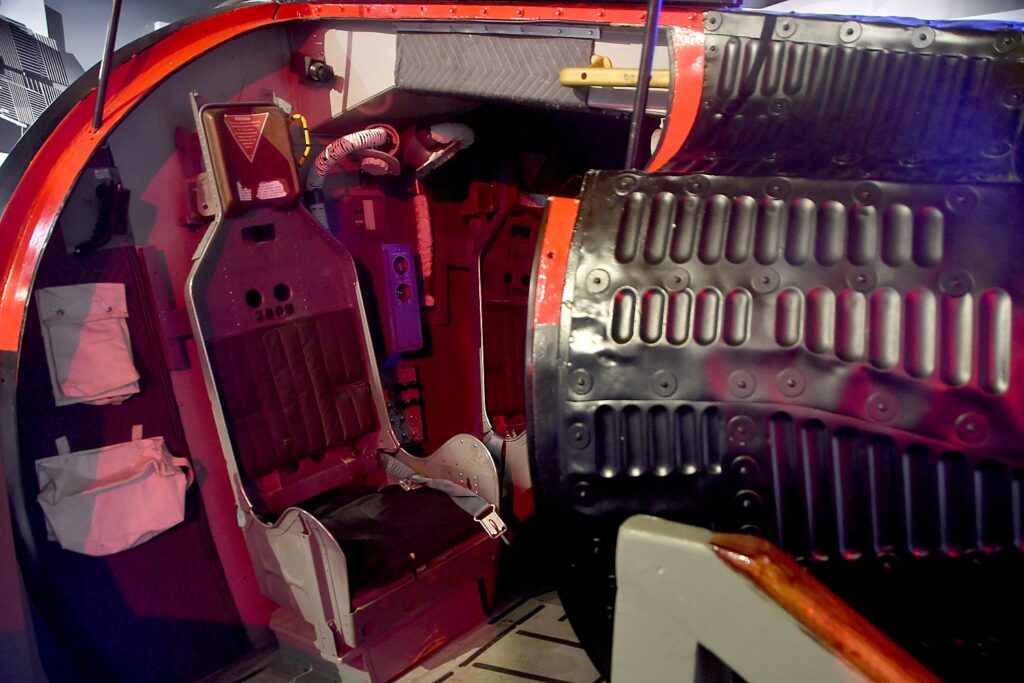

The Cu Chi Tunnels are an immense network of connecting tunnels located in the Củ Chi District of Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), which the Viet Cong used to launch guerrilla warfare against the Americans during the Vietnam War. The site has over 120 km of underground tunnels with trapdoors, living areas, storage facilities, armory, hospitals, and command centers, and were used going back to 1948 against the French, and later against the Americans.

The visit is profound, and though the script is written by the victors, is appropriate to represent the side that wanted to push out colonists (though in retrospect, I realized that there was no real mention of the fact that the South Vietnamese leadership didn’t want the Communist North Korean leadership to take over, either – nothing is simple, especially not in the world of geopolitics).

You have to appreciate the commitment and courage and sacrifice of the Viet Cong in living the way they did – creating a virtually self-sufficient underground community, planting booby traps for the Americans, repurposing unexploded bombs into weapons and old tires into sandals, cooking only at night and channeling the smoke to come up in a different place (where it would look like morning steam, so not to give away the location of the tunnels).

We get to climb into a tunnel, and can go 20, 40, 60, 80 up to 160 meters, seeing just how tiny they were – you have to crouch all the way through and sometimes even crawl. It is hot, uncomfortable, you feel claustrophobic and it is a bit terrifying.

Our tour guide leads us through – he is incredibly kind and considerate. He gives special attention to the children who are visiting – grabs them when they want to go down into a tunnel where he fears there could be scorpions (he shows us carcasses), snakes or rats.

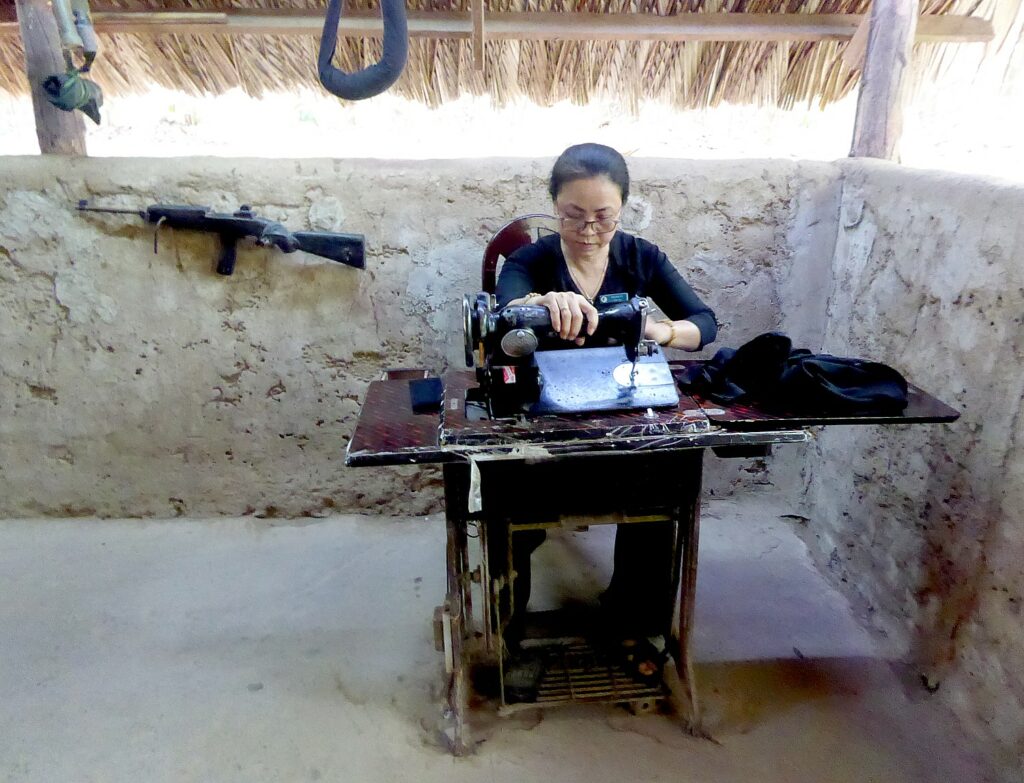

There is also a shooting range where you can shoot an AK 47 or M16 (extra charge), but the constant sound of gunfire gives you some sense of what the people were living through. There was a hospital, a sewing area where they would make uniforms, there is a trap door to escape. We see where they would have made sandals from old tires. We watch a woman demonstrate making rice paper; another at a sewing machine where she would be making uniforms, a rifle hung close by on the wall.

All of these things which we see above ground are recreated from what they would have looked like underground.

There were also constant bombings – B-52s could fly from the base in just two minutes time.

We get a sense of that in documentary-style films that are presented at the end. The film uses grainy black-and-white imagery with a narration that spoke of the commitment to save the Fatherland from US aggression, which basically depicts much of what we have visited in the tunnels, but as these places were used during the war. I must say that as gruesome as the film is, the only “propaganda” element is that it does not discuss the civil war between North and South Vietnam, only that the war was perpetrated by the Imperialist United States.

Many of the scenes show women and girls as soldiers. “They took unexploded bombs and turned them into their own weapons; they took from the Americans the new guns but never stopped using traditional weapons – the traps devised to hunt animals were used against the American enemy… Every person can be a hero. They had to live in poverty but wouldn’t retreat. A rifle in one hand, a plow in the other. Attacked in the morning, they farmed at night so they had enough food to win the war. The Americans wanted to turn Cu Chi into a dead zone, but they lived underground.”

But what we see in the film looks exactly like what was put on view here. We see people climbing through tunnels to the sound of gunfire.

“Male and female enrolled to kill enemy..Cu Chi guerrillas would rather die and become hero for killing Americans… never afraid of hardship to kill Americans. In hardship, they came together.”

Believe it or not, they actually make the experience as pleasant and as comfortable as possible, which somehow masks the terror of the place. Children smile and laugh as they get to descend through the camouflaged openings in the ground.

We leave the tunnels after spending about two hours here.

On the way back, the guide asks if we would like to make a detour to visit a factory, created by the government to employ people who were handicapped because of coming upon unexploded ordinance, or who had birth defects as a result of the chemical weapons used against the Vietnamese. Originally the factory, 27-7 HCMC.Co.Ltd, produced cigarettes, but today, Handicapped Handicrafts produce really beautiful handicrafts – mainly lacquered and inlaid items.

After returning to Saigon, I go off to continue my theme – visiting the buildings that the French built, starting with the magnificent Post Office (where I wind up spending close to an hour choosing from a stunning array of post cards, buying stamps and writing the cards, the sweat streaming down my face and stinging my eyes so that a nice lady hands me a tissue). Then onto the Reunification Palace (which I thought was open until 5 but closed entrance at 4), so I go on to the War Remnants Museum.

I have trouble following the map, so when I ask directions of a young man, he leads me through back alleys to the entrance of the museum, which I visit until it closes at 6 pm, because there is so much to see and take in.

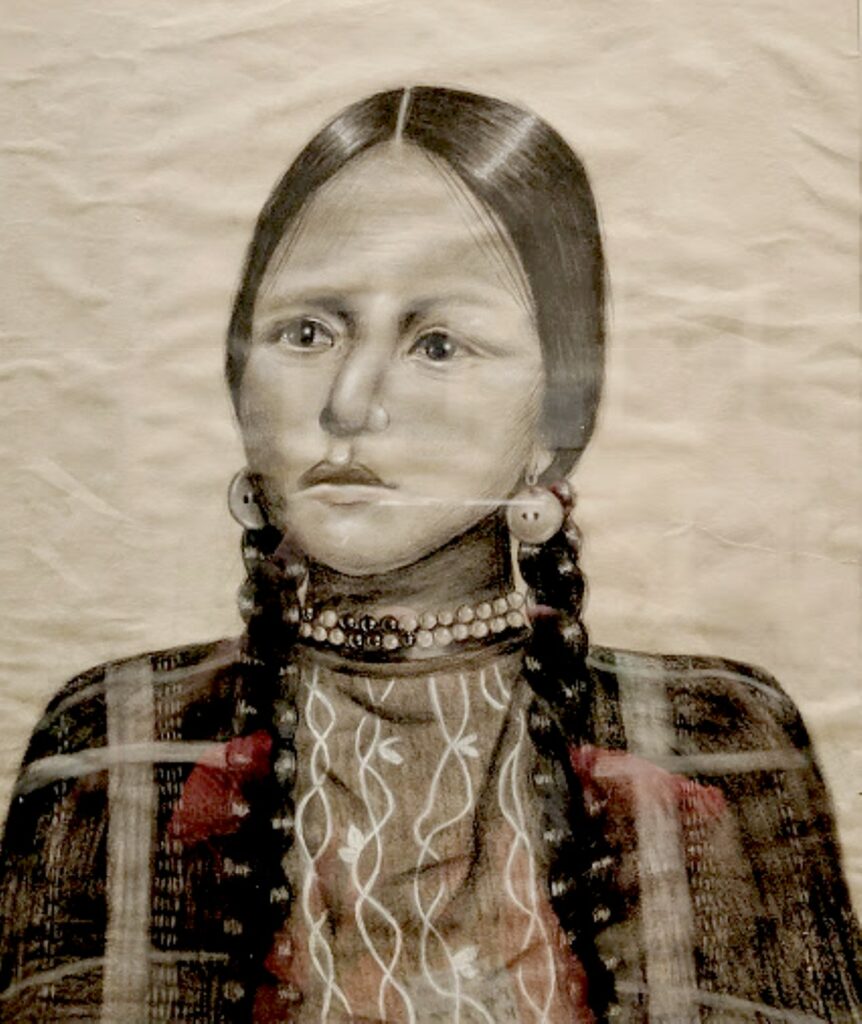

You should begin on the third level, which provides the “historic truths” (actually the background) for the Vietnam War, which more or less accurately presents the facts. On this level is a most fascinating exhibit that presents the work of the multinational brigade of war correspondents and photographers, along with a display of the dozens who were killed in the war.

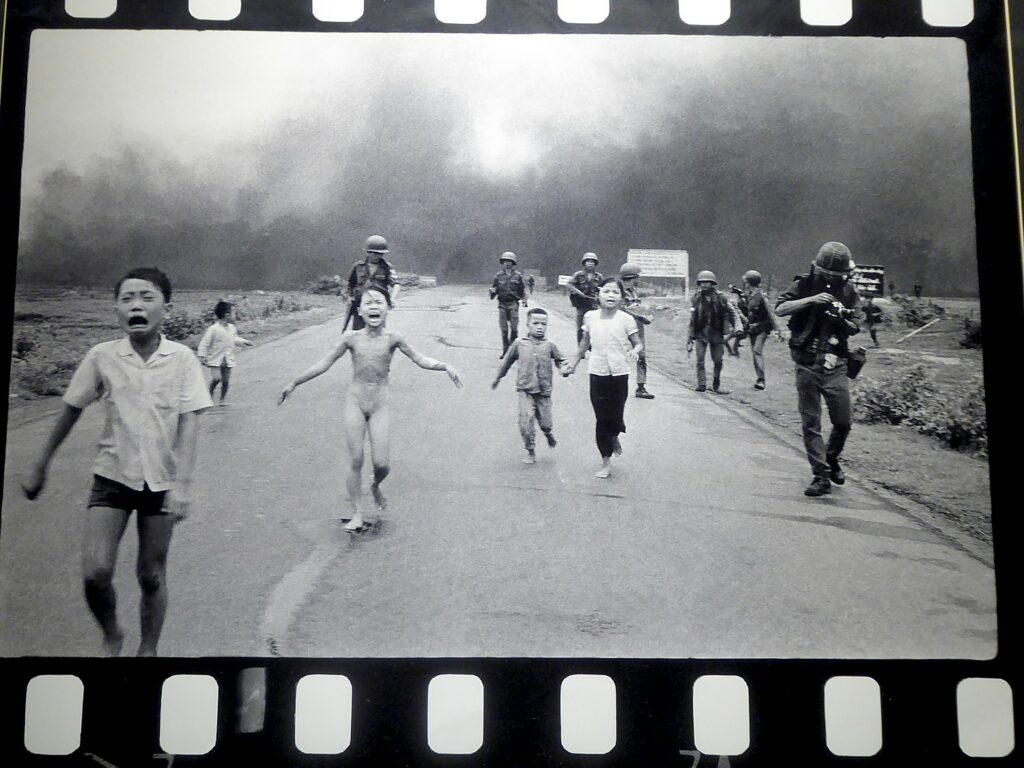

The photos are presented in an extraordinary way: showing the photo, then providing notes about the background, the context of the image, and the photographer. Here too, the language (which was probably produced by the news organizations that put on the exhibit), was accurate. Among them is the famous, Pulitzer-prize winning photo of “Napalm Girl” where, for the first time, I notice the soldiers walking along as this young girl is coming down the road in terror, their demeanor in such jarring contrast to these fleeing Vietnamese. The photos then and now are chilling, but today, they properly evoke shame and wonder why there has never been accountability for war crimes.

It only gets worse on the second level, where the atrocities committed during war are provided in the sense of artifacts, and details that could have, should have properly been used at war crimes trials. But none took place. Another exhibit documents the effects of Agent Orange.

The first floor, which should be visited last, addresses the Hanoi Hilton, the place where American prisoners of war, including Senator John McCain, were kept. Here, though, is where it can be said the propaganda offensive takes place – there are photos showing a female nurse bandaging an American’s head wounds, the caption noting how she had put down her gun in order to care for him. This exhibit brings things up to date, with the visits of President Clinton in 1994; in another section, it notes that Clinton’s visit brought the end of economic sanctions, and with the country’s shift to market economy, produced revitalization, as measured by the boom in mopeds.

But on the bottom floor, they show photos of Obama’s visit and most recently of Trump in Vietnam.

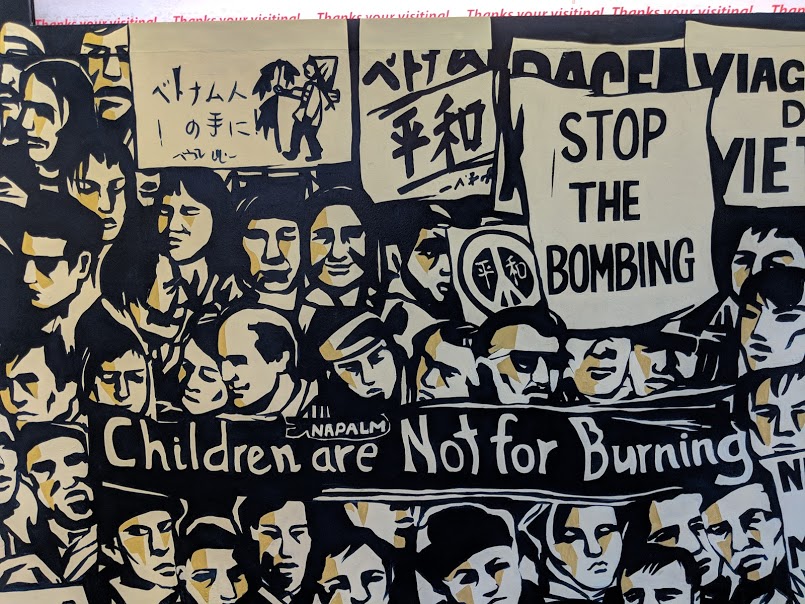

This floor also has an exhibit devoted to the peace movement in the US and around the world, with some famous incidents, such as the shooting of the Kent State four. There is a photo of John Kerry, who went on to be a Senator, Secretary of State and candidate for president, testifying to Congress in his military uniform, on the necessity of immediate and unilateral. “how do you ask a man to be the last man to dies in Vietnam? How do ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?

A special exhibition, “Finding Memories” attempts to recreate the struggle of the people of Hanoi and Haiphong to overcome the pain and loss of war. “It helps those who haven’t experienced wars to learn more through remarkable and humane wartime stories, especially the stories about American pilots in the ‘Hilton-HaNoi’. Finding Memories is an opportunity for Vietnamese people to develop greater pride for their victory – a 20th century miracle; for American pilots to recall a serene period of their lives; as well as for each and every visitor to understand the severe destruction and painfully grim nature of war, in order to call for all people to work together and dedicate our efforts to build a world of peace and love.”

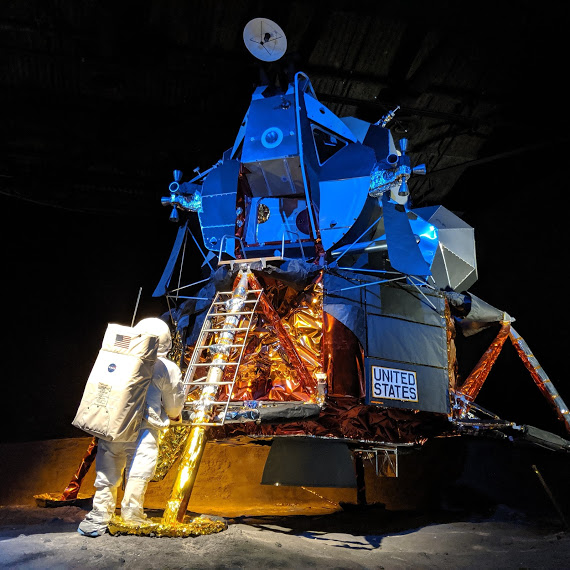

Outside are displays of captured American plane, tanks, and other items.

I look around for an American who might have served in Vietnam to get an impression, but did not find anyone, and saw a few Vietnamese (most of the visitors were Americans or Europeans), but only one or two who might have been alive during that time and wondered what they thought. Clearly the conclusion of the displays was in favor of reconciliation when just as easily, and using a heavier-handed propagandist language, could have stoked hatred. The exhibit is careful not to paint all Americans and not even all American soldiers as monsters but one photo caption is particularly telling: it shows an American hauling off an ethnic minority, noting “American troops sent to the battlefield by conscription knew nothing about Vietnam, thought the Cambodia people of ethnic minorities were living near Cambodia were collaborators for the enemy.”

I leave feeling that the experience is close to what you feel visiting a Holocaust Museum. And it is pain and remorse that is deserved.

We meet at 8:30 pm to hand in our score sheets and share stories – one team got up at 5 am in order to get to the floating market; a team was able to get on the street market food tour, where they take you around by scooter (they only take 8 and it was closed out); another took a cooking class.

We get our notice of where we are going next: be up at 6 am for 7 am bus to airport for 9:35 flight…. to Myanmar!

More information on travel to Vietnam at www.vietnam.travel.

The Global Scavenger Hunt is an annual travel program that has been operated for the past 15 years by Bill and Pamela Chalmers, GreatEscape Adventures, 310-281-7809, GlobalScavengerHunt.com.

See also:

Cities, Mountains, Boat and Beach: Letters Home from Honeymoon in Vietnam & Cambodia

______________________

© 2019 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures