By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

It wasn’t mining or farming that brought settlers to Banff. It was tourism. Banff was built for tourism. Even before the railroad (built to cajole the western territory to join Canada instead of the United States), even before three railway workers discovered the hot springs that pinpointed Banff as a destination and Canada’s first national park, and before Canadian Pacific Railroad built its world-famous, grand Banff Springs Hotel, this was a gathering place for indigenous peoples for centuries if not millennia.

Travelers, adventurers, pioneers, artists have come under the spell of this place – its majestic scenery, the heady feeling of pure crisp air at altitude – and so have entrepreneurs and innovators.

Two clever young entrepreneurs, the Brewster brothers, were among those visionaries responsible for building Banff – turning a fledgling guide service when they were just teenagers into Banff’s first tour company, then added hotels and bus operations.

Flash forward 100 years, and the long list of tourism enterprises they launched are under the Pursuit Collection umbrella, now part of a U.S.-based company, that stretches well beyond Banff, to Jasper and Watertown; to Glacier National Park in Montana, to Alaska and even to Iceland, including some that the clever brothers never could have imagined – Sky Lagoon, a new geothermal hot pool in Reykjavik, Iceland, and Flyover virtual reality experiences (where you get to sightsee an entire country in a matter of minutes) in Vancouver, Las Vegas, Iceland and soon Chicago and Toronto. And just opened, the Railrider Mountain Coaster – a 3,375-foot mountain coaster at the Golden Skybridge in Golden, B.C. (the first of its kind in Western Canada it is the fastest and largest mountain coaster in Canada).

I get an actual flyover experience as I jet from Toronto across Canada’s vast plains, still blanketed in white snow, to Calgary, Alberta, at the foothills of the Canadian Rockies, to sample many of the Pursuit Collection services that make Banff such a delightful, year-round visitor experience.

I am following an endless stream of visitors to Banff, lured by the spectacular majesty Canada’s Rocky Mountains that 150 years ago competed with the Alps for mountaineers.

My introduction to what the Brewster boys accomplished is the Brewster Express bus service from Calgary International Airport to the Mount Royal Hotel (also Pursuit Collection) in Banff. The service is so efficient – both the agent at the Brewster desk and the driver have my name on a list, and I board a comfortable coach to enjoy the scenic ride that takes 90-120 minutes. “Welcome to Calgary,” the driver rings out cheerily, “the sunniest place in Canada.” We set off after he gives us a safety talk.

I check-in to the Mount Royal Hotel, founded in 1908 as the Banff Hotel, making it one of Banff’s oldest hotels, which the Brewsters acquired in 1912. In fact, the Cascade Hotel, an older hotel, is incorporated into the today’s building with four wings, each representing a different era, that spans the entire block.

The Mount Royal Hotel is perfectly situated, walking distance to everything. The view from my window onto the charming streetscape with the mountain peaks behind takes my breath away. The service is wonderfully friendly, hospitable, with every creature comfort provided – the rooms are even equipped with ear plugs and white noise machine (the hotel is right on the main street which has a lively nightlife).

I arrive before meeting my group of three other travel writers and our Pursuit Collection host, early enough in the afternoon to wander about the small, picturesque village, almost entirely ringed by mountain peaks that seem to flow right into the town.

The entire town of Banff is set within the national park– Canada’s first and since 1984 also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. While the boundaries of the park expanded out from the hot springs (now a national historic site) to 2,564 square miles (96 percent wilderness), the town’s boundaries are fixed and buildings are limited to three stories high (except for the Mount Royal, with four stories, which is grandfathered). Probably 95 percent of the town’s population of 8,000-9,000 works in tourism (you have to work in Banff in order to buy a house but do not own the land). So it is so interesting to also have stores and services that are for local, everyday use – the high school is right on Banff Avenue (the main street), a hardware store, a grocery store.

From a summer retreat – people have been coming on the Canadian Pacific Railroad since 1888 – and beginning in the 1930s when the Brewsters developed Sunshine Mountain into a ski center, Banff has become a year-round destination and today, an iconic ski destination with three ski areas within the national park.

Much of how tourism developed here is due to the Canadian Pacific Railroad, which not only created the means for bringing tourists but built the grand Banff Springs Hotel, opening its doors in 1888.

But so much more is due to the work of other pioneers and entrepreneurs: the Brewster brothers, who from a young age (10 and 12), realized that the tourists wanted to be guided for sightseeing, and exploring the wilderness.

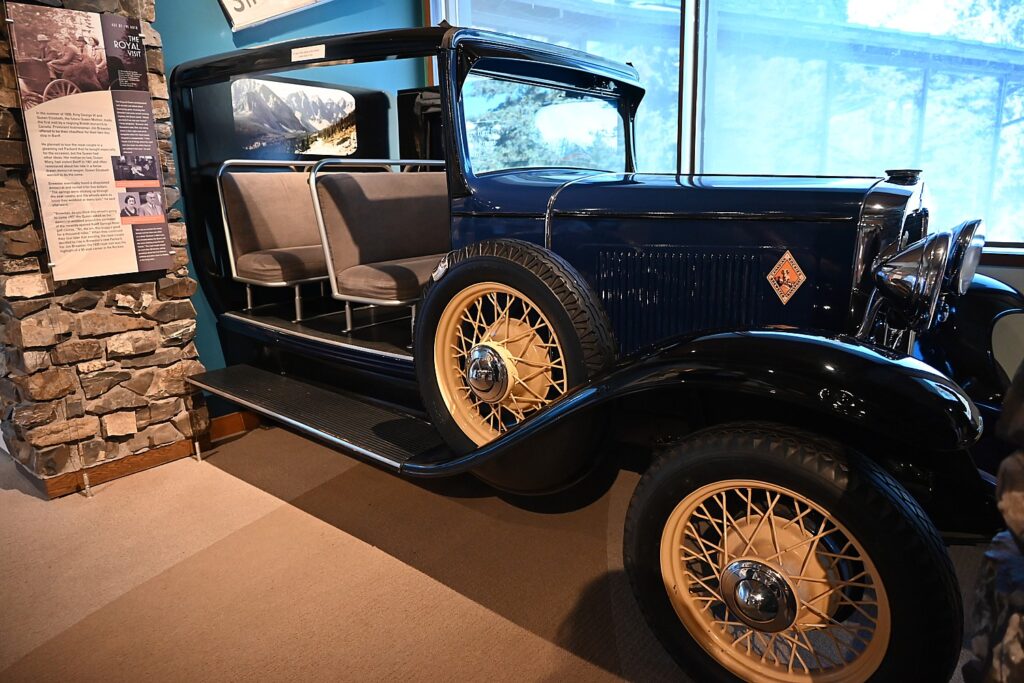

Beginning in 1892, the clever lads hired out as guides, becoming the exclusive outfitter for CP Railroad’s guests, then created a sightseeing service which grew into a fleet of 70 horse-drawn “Tally Ho” carriages; then, as automobiles became popular in the 1920s and 1930s, they introduced specially designed open-top touring vehicles (replicas are now used in a new incarnation of the open-top sightseeing tour).

Brewster, which celebrated its 100th year, was acquired by Viad, a Phoenix-based investment company, which in 2014, put the various tourism services and experiences under one umbrella, rebranded as Pursuit Collection. This includes the Brewster bus service, Open-Top Sightseeing (in Banff, Jasper and Watertown), the Mount Royal Hotel, Elk & Avenue Hotel, the Banff Gondola (most popular attraction in Banff for good reason), and restaurants including the Sky Bistro (atop the gondola), Farm & Fire, and Brazen, and the Lake Minnewanka marina, cruises and snack shop, plus its Columbia ice field glacier tours (summer). Its tourism operations span Montana, Alaska and now Iceland. (You can book all the elements and packages on the website; res agents can give ideas, counsel, and there are sample itineraries, www.pursuitcollection.com)

We get a preview of this season’s Open Top Sightseeing tour in the new, custom built vehicles to explore the people, places and moments that have made Banff. The vintage-inspired automobiles have the look and feel of the 1930s—including a fully-open roof (but with modern comforts like USB charging ports) and a guide dressed in period costume.

Our guide for this preview is Natalie Wuthrich, Open Top Touring’s manager, who tells us that they re-created the open top vehicle from Brewster’s original mold, put on top of a Ford 550 base, then stretched (actually putting two chassis together) so they accommodate 19. She adds that each of the three vehicles has its own personality and quirks (like the windshield wiper goes on by itself). We also get a safety talk before she pulls away from the hotel (three emergency exits!).

The 90-minute tours are offered eight times a day in Banff, and four times in Jasper and Watertown. (The vehicles are available for private charter, wedding, corporate transfer, shuttles for shopping loops.)

She plays music to accompany the mood for the story she is telling. We set out to Billie Holiday’s “A Fine Romance.”

We pass Tanglewood House – one of first of Banff’s buildings, which was originally used as a trading post and post office. Today’s owner is a celebrity of sorts – he makes coffee.

She points to a yellow house styled after houses that were literally transported to Banff in the 1930s from 15 miles away in Bancoff, a coal mining town. When the mine shut, they moved 38 houses using trolleys, in 40 days. Originally sold for $50/room ($250 in today’s money), the homes are now worth $1.5 million each – a reflection of how scarce living space is. In order to purchase a house in Banff, which is within the National Park, you need to reside in Banff and work, own a business, or be a spouse of someone who does, and you only lease the land it’s on because the land belongs to the nation.

We pass by the lovely Banff Center for Arts & Creativity, founded in 1933 to promote visual and performing arts, which offers a hotel, fitness center, artist residencies, studios, and hosts the Banff Mountain Film Festival.

Driving passed Tunnel Mountain, we learn there is actually no tunnel in Tunnel Mountain.

“The railway needed to get to Banff, but a mountain was in the way. The engineer planned to blow a tunnel through mountain so that passengers would pop out at Banff Springs Hotel for a ‘wow’ reveal – but it was too dangerous and expensive, so, instead, the railroad used the natural lay of land and followed the river.” But the name stuck, she says, possibly as an insult. (There is a petition to rename Tunnel Mountain to its indigenous name, Sacred Buffalo Mountain, because it has the shape of a sleeping buffalo.)

Tunnel Mountain is a popular hike right from downtown Banff, with the reward of a 360-degree view from the top.

We come to the “Castle in the Rockies” – the Banff Springs Hotel. “It was the vision of Sir William Cornelius Van Horne, the general manager of the Canadian Pacific Railroad who was responsible for completing the transcontinental line (in 1885). He built a coast to coast train, but where would the people stay?” in order to experience this magnificent place. (Van Horne designed the hotel and initially, was built backwards, with the better views going to the staff; the originally burned down and was rebuilt in 1914.)

Guests came on the train and stayed at the hotel. Bill and Jim Brewster – their father was a dairy farmer who supplied Banff Springs Hotel – realized the guests needed something else to do, so they started guiding back packers, pack horses, then Tally Ho’s, the horsedrawn carriage. When automobiles became popular in 1920s and 1930s, they devised 12-passenger open-top automobiles, ultimately building a fleet of 60 vehicles.

The Brewsters hosted major celebrities – there is a marvelous photo we see later at the Whyte Museum of the Brewsters driving King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in their horse-drawn carriage on the royals’ visit to Banff during their 1939 tour of Canada.

The music now is “Stompin at the Savoy,” by the “King of Swing” Benny Goodman, who stayed at the hotel in 1933. As a condition of coming, Natalie relates, he required they build a landing strip so he could pilot his own plane there because he refused to take the train. The landing strip still exists, mainly for emergency and is popular with foraging animals.

We stop to take in the breathtaking view of Mount Rundell, Sulphur Mountain and Tunnel Mountain.

We drive up to Norquay – one of three ski areas within Banff National Park. One of the oldest ski hills, its 1948 double chair lift still runs (Marilyn Monroe was photographed here during filming of “River of No Return” in 1953). Among the ski jumpers who came for the 1988 Olympics in Calgary who practiced here was “Eddie the Eagle” who didn’t have the money for the lift ticket, Natalie relates as she serves us hot chocolate.

Natalie regales us with stories of the colorful characters who populated and built Banff.

Bill Peyto, who was an early park warden (1913-1937), was a recluse and a trapper who collected animals for the zoo. Opened in 1907, the zoo showcased cougars, elk, monkeys, and a polar bear known as “Buddy” was closed in 1937 over concerns over animal cruelty, and is now Banff’s Central Park. On this day, he trapped a lynx, sedated it, and decided to get a drink in the Alberta Bar (where Brazen restaurant is today in the Mount Royal Hotel), with the sedated lynx still wrapped around his neck, until it wasn’t.

We pass the Trading Post, which I recall visiting decades ago. It was established by another of Banff’s important founders, Norman Luxton, who came to Banff in 1902 and earned the nickname “Mr. Banff” for all the ventures he launched. The more I learn about Luxton, the more I admire the man. He seems to have been a mix of P.T. Barnum, Wild Bill Hickok, William Hearst, and Thor Heyerdahl, and I can’t get enough of his story, especially as I explore Banff.

Luxton was a real promoter, possibly picking up a few tips from P.T.Barnum, the famous circus promoter. Natalie relates how Luxton got a black bear orphan cub, ‘Teddy,” which he put outside his Trading Post, as “a sure drawing card for eastern city-slickers looking for a piece of the Wild West.” People, who came from all over the world to see Teddy, would buy salty caramel chocolate treats at the trading post to feed the bear, until a boy, as a prank, laced chocolate with chili peppers that so agitated the bear, the park superintendent had the bear removed (he lived with a hotel keeper in Golden) and banned keeping any wild animal as a pet.

Later, when I visit the Trading Post, I see Luxton’s “Merman” from Fiji– a real homage to Barnum who first exhibited his in 1842- which Luxton probably used in place of the bear as a lure to visitors to the store. Luxton’s ventures also included a newspaper, a theater, a hotel, a museum showcasing First Nations (still operating, a must-see) and boat tours – most still in operation today.

Luxton began the Winter Carnival events in 1917 that helped turn Banff into a snow-sports destination and from 1909-1950, organized the Banff Indian Days, an annual weekend event that brought locals, tourists and First Nations peoples together in Banff.

Pursuit Collection’s website makes it easy to plan a three-day itinerary out of Banff. A Pursuit Pass provides savings up to 40% when you book Banff, Jasper and Golden’s attractions together, including the Banff Gondola, Columbia Icefield Adventure, Golden Skybridge, Open Top Touring, Lake Minnewanka Cruise and Maligne Lake Cruise.

The Columbia Icefield Adventure (which hadn’t yet started for the season when we visit) features the defining geological heart of Jasper National Park. It includes an Ice Explorer Tour on the Athabasca Glacier (a 10,000-year old sheet of ice you can walk on), admission to the glass-floored Skywalk to walk at the cliff’s edge, and return transportation from the Glacier Discovery Centre.

Pursuit Collection has just opened its newest attraction, the Railrider Mountain Coaster – a 3,375-foot mountain coaster at the Golden Skybridge in Golden, B.C., 90 minutes from Banff. The coaster is the first of its kind in Western Canada and is the fastest and largest mountain coaster in Canada.

The Railrider Mountain Coaster races through an old growth forest between Canada’s two highest suspension bridges. It features an up-track that takes riders 1,180 feet up the canyon, before they descend 2,195 feet, reaching speeds of up to 40 kilometers per hour. Riders then coast under the lush canopy, around a 360-degree loop, through a 50-foot tunnel and finally shoot out onto a cantilever that extends over the majestic Columbia Valley. The coaster features state-of-the-art technology that allows riders to choose their own level of adventure (www.goldenskybridge.com).

You can find Pursuit Collection’s services and attractions at https://www.pursuitcollection.com/; to book Pursuit Collection’s Banff and Jasper experiences, https://www.banffjaspercollection.com/.

Next: Pursuit Collection Offers Feast for Senses and the Soul in Banff

_____________________________

© 2023 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/KarenBRubin